Polio Vaccine: How the US' Most Feared Disease Was Eradicated

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ebola may be the most feared disease right now, but for most of the 20th century, outbreaks of another disease left thousands of people paralyzed or confined to breathing machines: polio.

Poliomyelitis, which was also sometimes called infantile paralysis, primarily infected children. However, adults — including Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who later became president — also got the disease.

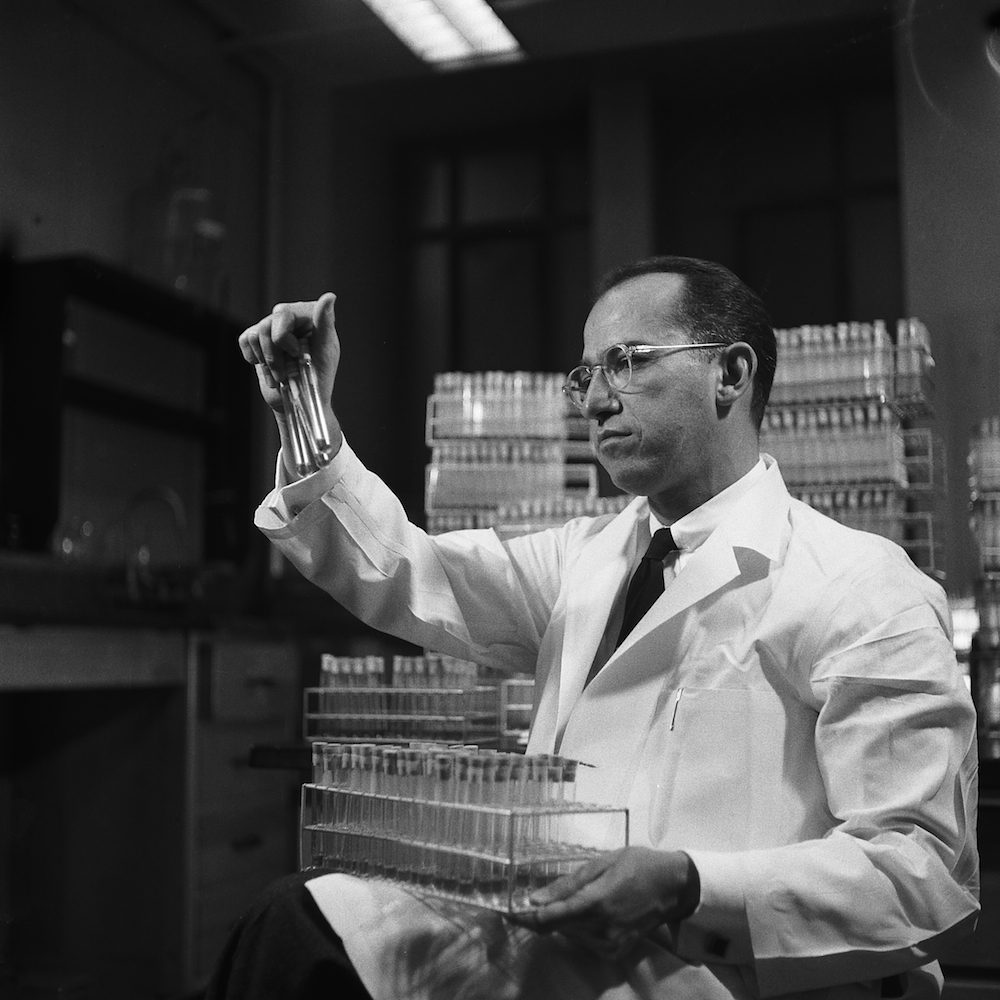

But thanks to the vaccines developed by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, combined with one of the most successful vaccination campaigns in history, humanity turned the tide against this horrifying disease. [In Images: How the Polio Vaccine Made History]

Today (Oct. 28) would have been Salk's 100th birthday (he died in 1995), and there's a new exhibit at NYU Langone Medical Center honoring the legacy of Salk and Sabin. The exhibit opened last week and runs through Nov. 7.

A dreadful disease

Thousands of American children were paralyzed by polio, which is caused by a virus that is usually passed by the fecal-oral route (from feces to mouth), by way of food, water or poor hygiene. Some people infected with the virus did not develop any symptoms but could still transmit the disease.

In about 1 in 200 cases, people with polio developed paralysis, and although some recovered from their paralysis, many of these victims were paralyzed and confined to crutches or wheelchairs for life. Children whose breathing muscles were paralyzed were placed inside a sealed ventilator chamber known as an iron lung.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Kids spent years in them, [only coming] out for short periods," said David Oshinsky, a medical historian at NYU Langone Medical Center and author of "Polio: An American Story" (Oxford University Press, 2006). One woman spent 50 years in an iron lung, he said.

In 1938, Roosevelt founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which later came to be known as the March of Dimes. It was the first major research effort to combat polio, Oshinsky said.

At that point, not much was known about polio, other than that it was a disabling disease caused by a virus, and that it was highly contagious, said David Rose, an archivist for the March of Dimes.

Salk's legacy

The organization funded the research of Salk, who was then a virologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and was working to develop a vaccine from the killed poliovirus. By 1953, Salk had a viable candidate. He tested the vaccine on himself to prove its safety.

In 1954, the March of Dimes launched a nationwide trial of the vaccine. The trial involved 1.8 million children, who became known as the "Polio Pioneers." Only about half of the children received the vaccine, while the other half received a placebo or nothing at all.

Parents didn't know if the vaccine would work, but they allowed their children to get it anyway, because they thought it couldn't be worse than polio, Oshinsky said.

The campaign was a huge success, and newspaper headlines trumpeted the end of polio. "Americans went absolutely nuts," Rose said. "It was really a moment of jubilation, where science seemed to triumph [over the illness]."

The Salk vaccine was licensed, and the March of Dimes started a campaign to get everyone vaccinated. The incidence of polio dropped dramatically, from tens of thousands of cases to dozens or hundreds, Rose said. In fact, the rate of polio dropped so sharply that in 1958, the March of Dimes changed its mission from eradicating polio to promoting prenatal health.

Sabin's contribution

Meanwhile, Sabin, a medical researcher and a rival of Salk, had developed his own vaccine — using a live but less potent form of the poliovirus — which became available in the 1960s. Rather than being injected like the Salk vaccine, the Sabin vaccine could be taken orally, making it much easier to administer.

By 1979, polio had been eradicated in the United States, but remained in other parts of the world. In 1988, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF and The Rotary Foundation launched a global campaign to eradicate polio, relying heavily on the Sabin vaccine. Since the effort began, the number of polio cases has dropped by more than 99 percent, and there were just 416 reported cases in 2013, according to the WHO.

Today, polio outbreaks are still a worry, but the virus is only endemic to Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan.

However, because Sabin's oral vaccine contained a live virus, it actually caused polio in a very small number of cases (about 1 in 1 million), Oshinsky said. The United States switched back to using the Salk vaccine in the 1990s, but the Sabin vaccine is still used in places where it's difficult to administer injections.

"If we want to end polio, we have to use both," Oshinsky said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus