Deaths May Be Linked with Enterovirus: Why Some Kids Recover, Others Don't

The deaths of four children, possibly linked to their infections with enterovirus D68, are still puzzling to experts.

A girl in Rhode Island died last week after she developed both an infection with the enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) and also a rare infection with staph bacteria, according to a report from the Rhode Island Department of Health. Enterovirus D68 is a virus that causes flulike symptoms and has now sickened hundreds of people across the United States.

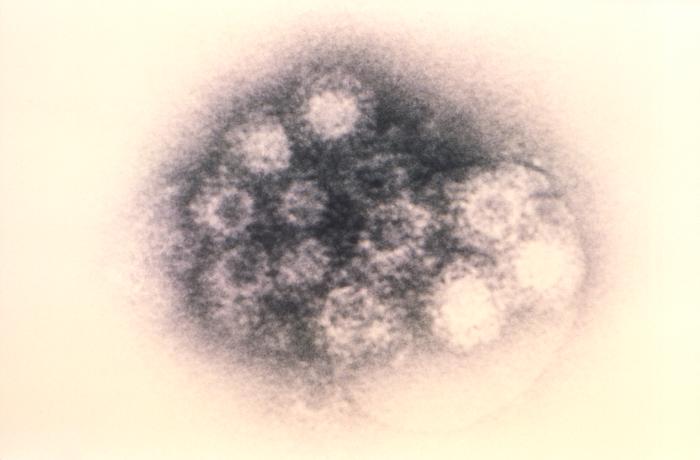

In addition to the Rhode Island child, workers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have found EV-D68 in the samples from several people who died in other states, but it's unclear what role the virus played in those deaths. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

Still, only a small proportion of people with EV-D68 will have symptoms worse than a runny nose, sneezing and a low-grade fever, health officials said.

"We are all heartbroken to hear about the death of one of Rhode Island's children," Dr. Michael Fine, director of the Rhode Island Department of Health, said in a statement. "Many of us will have EV-D68. Most of us will have very mild symptoms, and all but very few will recover quickly and completely. The vast majority of children exposed to EV-D68 recover completely."

But the reasons why some may die while others show very few symptoms remain unclear.

Double infection

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The CDC has confirmed cases of EV-D68 in 472 people, most of them children, in 41 states and the District of Columbia. Researchers originally identified the virus in 1962, and it's unclear why there is a sudden spike in its incidence now, health officials said.

EV-D68 symptoms typically look like those of the common cold, but can develop into wheezing and breathing problems. The virus is also in the same family as the poliovirus, and can cause muscle weakness or paralysis in a small percentage of cases, according to recent reports involving several children in Denver.

In the case of the girl in Rhode Island, the staph bacterial infection likely played a role in her death, said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who was not involved in the Rhode Island child's care. Staph bacteria are common and usually harmless, but can cause infections such as pneumonia, as happened in this case, Adalja said.

"Although [staph] lives harmlessly on a lot of people's skin, when it gets into the lungs, it can cause severe disease," he said. "The consequences can be pretty severe because you're already in the hospital with enterovirus, and now you got a secondary infection, which pushes it over the edge."

In fact, such infections are common in people with respiratory illnesses, Adalja said. For example, during the 1918 influenza pandemic, the majority of people who died were not killed by influenza virus infection, but by secondary bacterial infections, he said.

Immune system factors

Still, it remains unclear why EV-D68 itself is asymptomatic in some people, but causes devastating infections in others. However, it's likely a combination of factors involved with each person's immune system, Adalja said.

"That is something that is on the cutting edge of research, understanding how infectious diseases interact with the immune system and produce different illnesses in different people," he said.

There is no vaccine or treatment against this illness, but doctors recommend several ways to avoid contracting EV-D68. People should wash their hands, avoid touching their faces and help children with asthma manage their symptoms, according to the CDC.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.