How Often Does Enterovirus D68 Cause Paralysis?

Several children in Denver have developed limb weakness or paralysis after contracting respiratory illness, and four of the children have tested positive for enterovirus D68, the virus that has now sickened more than 400 people in 40 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It is not yet completely clear whether enterovirus D68 caused these children's neurological symptoms. Health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said on Friday (Sept. 26) that they are investigating the matter and searching for similar cases in other states that may have gone unreported.

"It's at the top of our list, but those investigations are still continuing, and I think we have not yet determined conclusively that D68 is the cause," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease expert at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.[7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

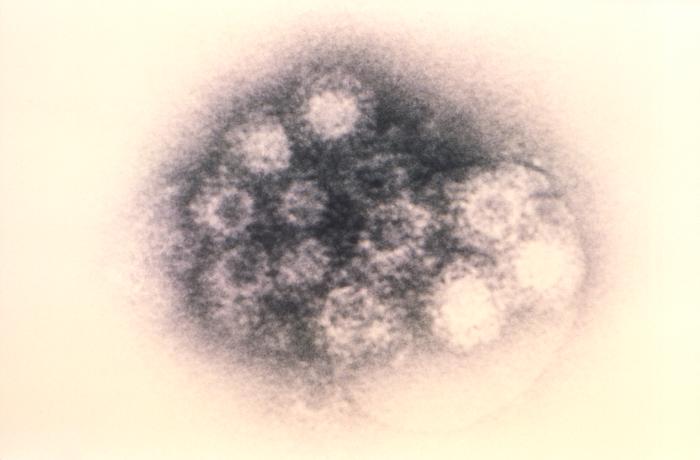

Enterovirus D68 is a rare virus and is in the same family of viruses as poliovirus; it can cause mild to severe respiratory illness. This year, outbreaks of infection with enterovirus D-68 have been reported in 40 states and the District of Columbia. The virus sickened at least 277 people between mid-August and Sept. 26, according to the CDC.

How enterovirus D68 could cause paralysis

Paralysis is not a common symptom of enteroviruses other than poliovirus, but is a possibility, according to the CDC. Enterovirus D68 generally targets the respiratory system and causes flulike symptoms, but it can get into the nervous system, and that's how it may cause muscle weakness or paralysis, Schaffner said.

"All the viruses in this enterovirus family can do this, but they do it very rarely," Schaffner said. To compare this virus to polio, he used an analogy: "The polio virus does this professionally. All the others are amateurs in creating paralytic illness."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Once in the nervous system, the enterovirus attacks certain cells that send signals to the muscles. The virus can cause inflammation, so that the cells don't work as well, or the virus can actually get into the cells and destroy them.

"Sometimes, as the inflammation recedes, you can get some restored function. But if those cells in the spinal cord have been actually killed, you're left with some permanent paralysis," Schaffner told Live Science.

It is not clear why in some cases the virus reaches the nervous system, while in others it doesn't, or what could be done to prevent a nervous system invasion if a person is infected, he said.

"Most of the children who are infected don't get this [paralysis]. Why the virus, on rare occasions, moves from the throat into the spinal cord, we don't know," Schaffner said.

How commonly can this happen?

This is not the first time that enterovirus D68 has been tied to paralysis. Last year, five children in California developed a poliolike illness that caused severe weakness or paralysis in their limbs. Two of those children tested positive for enterovirus D68. (In the other three children, the researchers were not able to find the cause of the paralysis.)

Still, doctors consider the risk of paralysis in someone infected with enterovirus D68 to be very low, Schaffner said. Even in the case of polio, paralysis occurs in only 1 in 200 cases of infection.

The nine children affected in Denver are between 1 and 18 years old, and all showed "spots or lesions in the grey matter of the spinal cord on MRI scans," Dr. Larry Wolk, the chief medical officer and executive director for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, told ABC News.

Eight of the children in Denver were tested by the CDC, with four testing positive for enterovirus D68. Two others tested positive for different strains of another enterovirus, and the results for two children are not ready yet. The CDC could confirm that most of the children had previously been vaccinated against polio, so polio could be ruled out as the culprit.

But even the four children who tested positive for D68 have created a puzzle for the researchers, Schaffner said. The virus was found in these children's throats, and not their cerebrospinal fluid, which is found in the brain and the spine. "Often when an enterovirus causes paralytic illness, you can recover the virus from the cerebrospinal fluid," Schaffner said.

It's also unclear why there haven't been reports elsewhere of paralysis occurring in children infected with this virus, Schaffner said. A newly launched investigation and notices sent to children's hospitals across the country may help find some answers, he said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.