Rare Respiratory Virus Suspected in 12 US States

An uncommon virus has caused clusters of severe respiratory illness among children in at least two U.S. states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, 10 other states are investigating possible cases of this virus, the CDC said. Missouri and Illinois reported the clusters, and investigations are taking place in Colorado, Kentucky, Kansas, Iowa, Ohio, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Georgia and other states, according to ABC news. (Two states investigating cases have not been named).

Recently, health officials in Chicago and Kansas City, Missouri, notified the CDC that hospitals in those areas were experiencing an unexpectedly high number of cases of severe respiratory illness, Dr. Anne Schuchat, director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said today in a news conference.

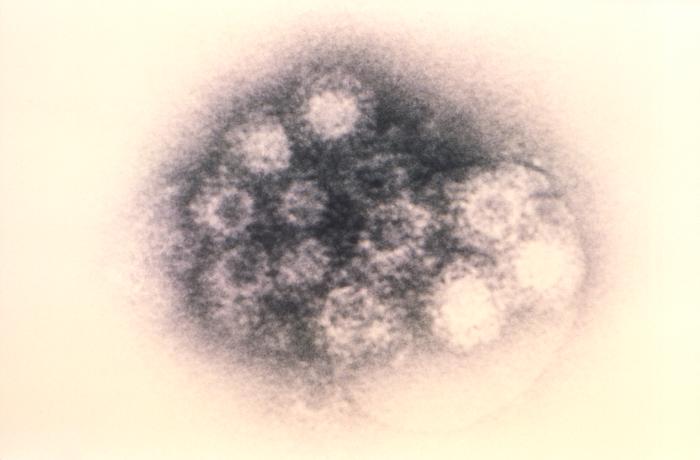

Researchers at the CDC tested samples from some of the sick children, and found that 19 out of 22 samples from Kansas City, and 11 out of 14 samples from Chicago tested positive for a rare virus called enterorvirus D68 (EV-D68), Schuchat said.

Sick children in these clusters ranged in age from 6 weeks to 16 years old, and more than half had a history of asthma or wheezing, Schuchat said. Common symptoms of the hospitalized children included wheezing and difficulty breathing.

Enteroviruses are common viruses that cause a range of symptoms, including coldlike symptoms, fever and rashes. However, there are more than 100 different types of enterovirus, and reports of EV-D68 in the United States are rare, Schuchat said. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Most people infected with enteroviruses have no symptoms or have mild symptoms, but in some cases, these viruses can cause severe illness. The viruses are more likely to infect children and teens, Schuchat said. So far, no adults have been reported to be sick with EV-D68 in the recent clusters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because reports of EV-D68 have been rare, health officials don't yet know the full spectrum of symptoms the virus can cause or exactly how it spreads, Schuchat said. However, officials said they believe it spreads through respiratory secretions, such as when someone coughs, sneezes or touches a surface, Schuchat said.

"We don't know as much as we'd like to know about this virus," Schuchat said.

While most cases of a runny nose won't turn into severe illness, Schuchat said U.S. parents should seek medical attention for their kids if the children experience wheezing or difficulty breathing.

Health care professionals should be aware that clusters of EV-D68 are occurring, and should consider EV-D68 in cases of severe respiratory illness that are not explained by other causes, Schuchat said.

The good news is that, although enteroviruses can cause severe illness, the length of the illness tends to be short, and it very rarely causes long-term health effects, said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. "Even on the severe end of the scale, [patients] get better quickly," Schaffner said. So far, no deaths have been reported linked to EV-D68, the CDC said.

Researchers don't yet know how far EV-D68 will spread.

"Enteroviruses are hard to predict," Schaffner said. "It would be unusual for the virus to spread all over the country, but this is an unusual virus, so we'll just have to wait and see."

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.