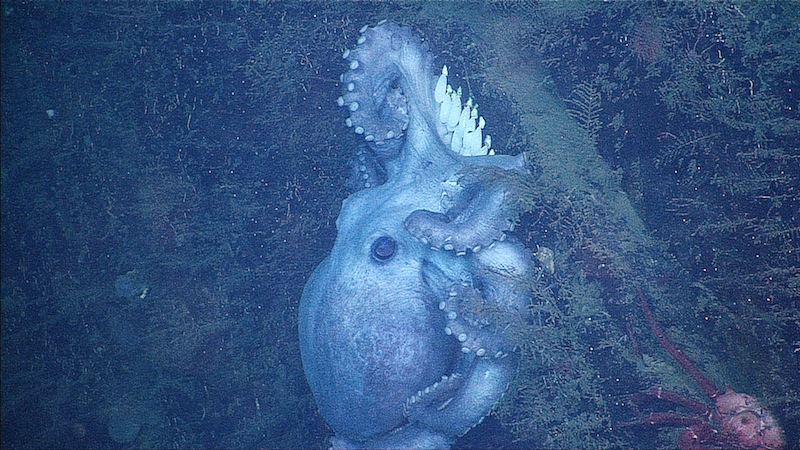

In Photos: Amazing 'Octomom' Protects Eggs for 4.5 Years

Record-Setting Parent

For 53 months, scientists watched a female octopus in the deep sea vigilantly guard a single clutch of eggs until they hatched. This was the longest brooding period scientists have ever observed — not just for octopuses, but also for all animals on the planet. [Read full story]

Deep-Sea Mom

Dubbed "Octomom," this female of the species Graneledone boreopacifica was found in the Monterey Submarine Canyon, a deep underwater valley off the coast of California. In May 2007, scientists snapped the first images of the octopus shielding her eggs with a remotely operated vehicle, ROV. [Read full story]

Extreme Octopus

"Octomom" was protecting her eggs on the nearly vertical face of a rocky outcrop, 4,583 feet (1,397 meters) below the surface. The scientists, led by MBARI scientist Bruce Robison, returned to the site 18 times and recognized the octopus by scars on her arms. They reported their findings in the journal PLOS ONE on July 30, 2014. [Read full story]

Parental Sacrifice

In all of those 18 visits, the scientists never saw "Octomom" leave her eggs or eat. They still aren't sure how she survived for so long. Most octopus species that have been well studied in shallower waters seldom live for more than one or two years. [Read full story]

Last Sighting

The last time the scientists photographed "Octomom" shielding her eggs was September 2011, nearly 4.5 years after she was first observed with her clutch. [Read full story]

Empty Egg Capsules

By the time the baby octopuses hatched, they would have been "mini-adults," Robison said. With the ability to swim and hunt, these creatures would generally have better chance of surviving in the hostile deep-sea environment than less-developed octopus babies that hatch after just a few weeks or months in shallower waters. The scientists counted about 160 egg capsules — a relatively low number for an octopus clutch. Instead of investing her energy into making thousands of eggs and hoping some hatchlings survive, "Octomom" invested her energy into protecting a smaller clutch and ensuring they all have time to develop. [Read full story]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.