Strongest Link: Wastewater Wells Triggered Oklahoma Earthquake Surge

Four fracking wastewater wells near Oklahoma City have caused hundreds of earthquakes since 2008, a new study finds.

The research offers the strongest link yet between the four massive injection wells, where wastewater is pumped underground for disposal, and the rapid rise in earthquakes in Oklahoma City. The findings were published today (July 3) in the journal Science Express.

"It's pretty clear high-volume pumping is having an impact on the natural system," said study co-author Geoff Abers, a geophysicist at Cornell University in New York. "Modern waste disposal wells can trigger earthquakes."

Wastewater pumping continues at the wells, which inject more than 4 million barrels (477,000 cubic meters) of water into the ground every month. [See Images of This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

Unnatural earthquakes

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is a method of extracting oil and gas that requires between 3 million and 5 million gallons (11 million to 19 million liters) of water per "frack." Afterward, the water is removed from the reservoir, but instead of treating the toxic wastewater, companies pump it back underground, into deep disposal wells.

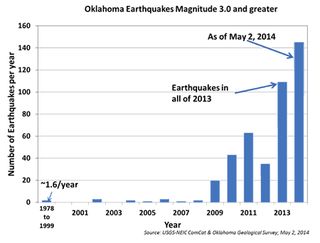

Oklahoma's earthquake activity started snowballing in 2009, at the same time as its boom in oil and gas production. More magnitude-3 earthquakes hit Oklahoma than California so far this year, Abers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I can't think of any natural process in any setting that would do this," he said. "It seems highly likely these things are tied to something that is anthropogenic."

Most of the quakes have been minor, but a damaging magnitude-5.7 hit in November 2011, triggered by a different set of injection wells, a previous study showed. Wastewater disposal is also blamed for an uptick in earthquakes in Texas, Arkansas and Ohio.

The four high-volume injection wells, located in southeast Oklahoma City, account for 45 percent of all earthquakes in Oklahoma in the past 10 years, according to the study.

But until now, the link between the four wells and Oklahoma's ongoing earthquake swarm wasn't entirely clear. That's because the quakes were ripping along faults more than 20 miles (32 km) from the pumping site.

"The increased earthquake activity in Oklahoma has been a puzzle to us, because, as intense as it was, it was not located particularly close to any industrial location that provided an easy explanation," said William Ellsworth, a seismologist at the U.S. Geological Survey's Earthquake Science Center in California, who was not involved in the research. "This study now provides more detailed understanding about how injection may be causing some of these earthquakes, even if the distances are surprisingly large."

A moving target

In the new study, researchers led by Cornell geologist Katie Keranen showed how fluid moving outward from the wells is causing earthquakes. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

Wastewater had been pumped into the wells since 2005, but operator New Dominion turned up the volume in 2009, according to records filed with the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industry. That rise in water pressure coincides with one of Oklahoma City's earthquake clusters, the researchers said.

Here’s how the water causes earthquakes:

Deep below the Earth's surface, the wastewater raises fluid pressure on faults, making it easier for them to slip and undergo an earthquake. The fluid reduces the effect of friction. This link, between injecting wastewater and causing earthquakes, has been known since the 1960s, when a deep injection well at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal near Denver triggered earthquakes.

"It's been known for some time that you can make earthquakes at a distance from wells, given enough time, enough fluid and the right setting," Abers said. "What's new is such a big area is affected."

To prove the link in Oklahoma City, Keranen and her co-authors precisely mapped the location of underground earthquakes and built a model of the subsurface geology based on oil exploration data. Their model shows how fluids migrating outward from the well can increase subsurface fluid pressure on small faults in the region even at a distance, triggering quakes. The pattern of actual earthquakes matches the pattern predicted by the model, the researchers found.

Unlike most natural earthquakes, the man-made earthquakes are relatively shallow, between 1.2 miles to 3.1 miles (2 to 5 km) below the surface. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Safer injection wells

Abers said the group hopes that studies such as theirs will eventually help lower the risk of earthquakes from wastewater injection wells. Currently, Oklahoma has no rules requiring seismic studies before a well is built, or earthquake monitoring during its operation. But many scientists think monitoring of injection wells, to identify and shut down wells at risk of triggering earthquakes, will eventually lead to less shaky ground in the central United States

"There are early signs that can be used to reduce the risk," Abers said. "There's a way to do this right. On the one hand, earthquakes are scaring a lot of people, on the other hand, a lot of people's livelihoods stem from the petroleum industry."

Oklahoma has more than 4,000 active injection wells, but only a handful cause earthquakes, scientists think. Shutting down the worst offenders has worked before to stop earthquakes, such as in Denver in the 1960s and more recently in Youngstown, Ohio, in March.

The Oklahoma Legislature is considering regulations, such as a "traffic light" system that would ignore small earthquakes, but close down wells when public safety is threatened.

New regulations might be welcomed in Oklahoma City, where an unsettling earthquake swarm plagued residents in June. One quake interrupted a morning newscast — the meteorologist on-air correctly guessed it was a magnitude-4. The U.S. Geological Survey has warned of the risk of bigger quakes in the future, up to a magnitude-6.

More than 200 earthquakes stronger than magnitude-3 have struck Oklahoma since January, double last year's pace. California has recorded more than 140 magnitude-3 quakes since January.

"The development of scientific understanding should permit regulators and operators to learn how to do this in a safe manner," Ellsworth said. "I think many of us feel we might be able to identify places where modifications in injection might reduce the risk."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.