3D Tumors Are Printed in the Lab

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

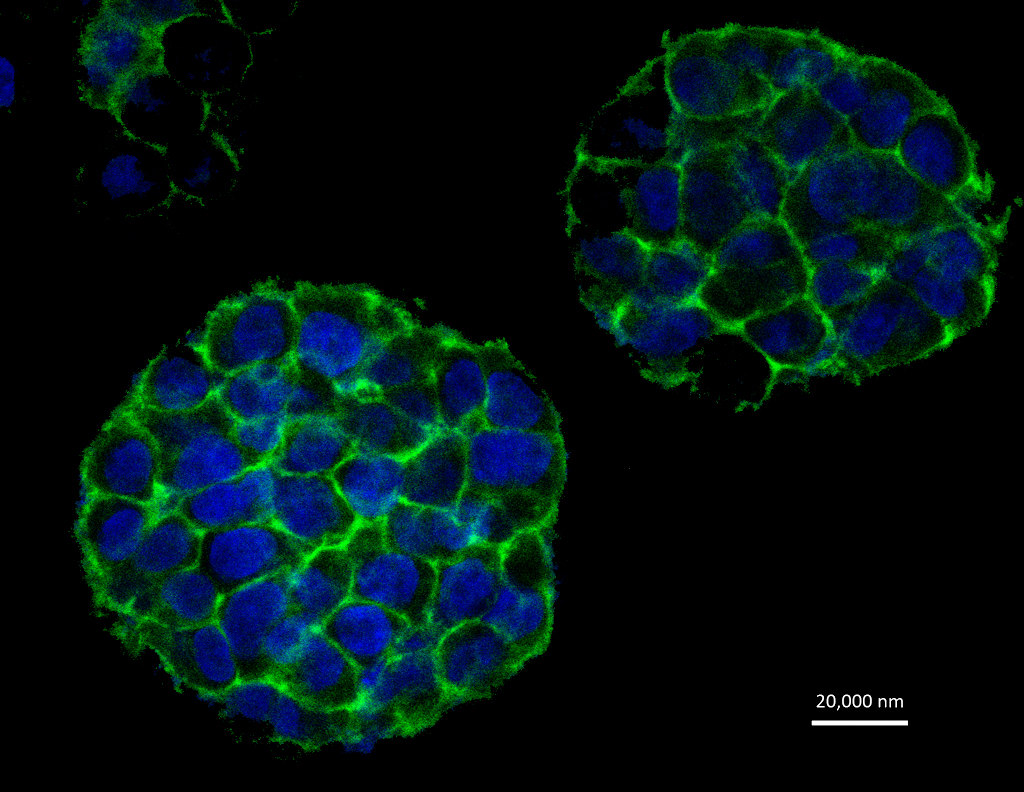

Using 3D printing, researchers have made a tumor-like lump of cancer cells in the lab, and they say this lump shows a greater resemblance to natural cancer than do the two-dimensional cultured cells grown in a lab dish.

This more realistic representation of a tumor could aid studies on cancer and drug treatments, the researchers said.

To build the tumor-like structure, the researchers mixed gelatin, fibrous proteins and cervical cancer cells, then fed the resulting mixture into a 3D cell printer they had developed. Layer by layer, the printer produced a grid structure, 10 millimeters in width and length, and 2 millimeters in height. [7 Cool Uses of 3D Printing in Medicine]

That structure resembles the fibrous proteins that make up the extracellular matrix of a tumor, the researchers said.

The cells were then allowed to grow, and after five days, the growth took on a spherical shape. The spheres continued to grow for three more days.

The cervical cancer cells used by the researchers were HeLa cells, the 'immortal' cell line that was originally taken from a cancer patient, Henrietta Lacks, in 1951. HeLa cells can multiply indefinitely and are the most common type of cells studied in cancer research.

In general, cancer studies involve cancer cells grown in the lab, which help scientists better understand the behavior of these abnormal cells. New cancer drugs are usually tested on such cells, in the lab, before being evaluated in human studies. Therefore, 2D models of cancer that consist of a single layer of cells grown in a dish have been created to assist research and testing of new drugs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, compared with such 2D cell cultures, the additional dimension of a 3D culture better reveals the tumor cells' characteristics, including their shape, their proliferation, and gene and protein expression, the researchers said.

"With further understanding of these 3D models, we can use them to study the development, invasion, metastasis and treatment of cancer using specific cancer cells from patients," said study researcher Wei Sun, a professor in the department of mechanical engineering at Drexel University, in Philadelphia.

"We can also use these models to test the efficacy and safety of new cancer treatment therapies and new cancer drugs," said Sun, who is also the editor-in-chief of the journal Biofabrication, in which the new research is published today (April 10).

The researchers also found that using certain parameters during printing made it possible for about 90 percent of cells to survive the printing process. The mechanical force of printing can damage cells.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus