Smartphone App May Help People Recover from Alcoholism

A new smartphone app may help people who have been treated for alcohol abuse continue in their efforts to avoid risky drinking, according to the results of a new study.

In the study, 170 patients recovering from alcoholismwere provided smartphones with the app, and were interviewed about their drinking habits at four, eight and 12 months after treatment. A second group of patients was provided with typical treatments, such as a therapy session once a month, but wasn't given the app.

At each interview, patients who used the app had fewer days of "risky drinking" in the last month (days in which they had more than 3 or 4 drinks) compared to those who did not use the app. [7 Ways Alcohol Affects Your Health]

In addition, those who used the app were more likely to say they completely abstained from alcohol in the last 30 days at all three interviews than those who didn't use the app. (About 52 percent of those in the app group abstained from alcohol, compared with 40 percent in the typical care group.)

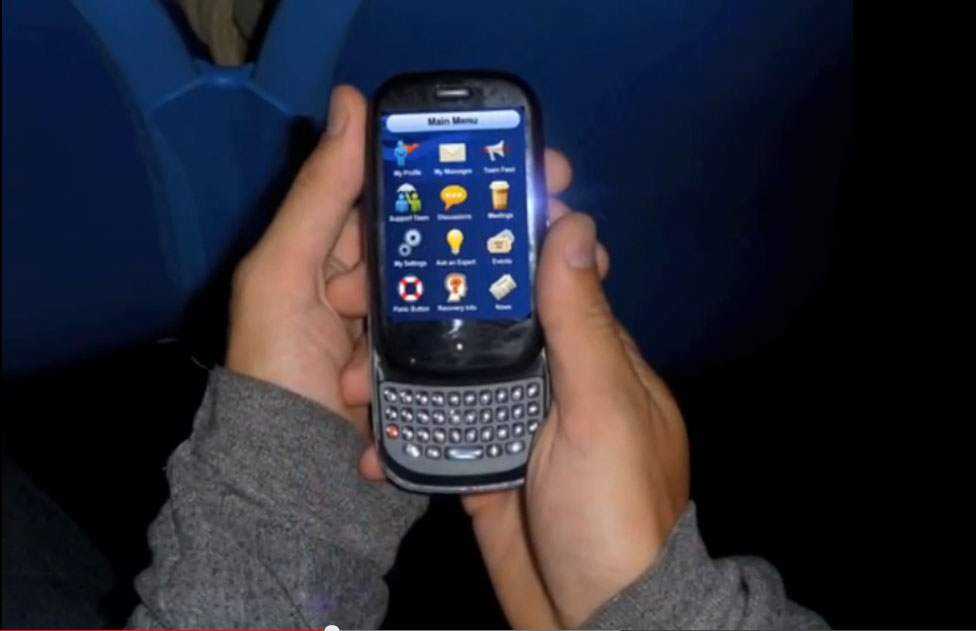

The app, called the Addiction-Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS), had several features intended to help patients, including a "panic button" that would alert close friends or family members if the patient was struggling with their addiction and needed support. The app also used the GPS on the phone to track the patient's movements, and would send a support message if the patient spent a long time near a bar they used to frequent.

Although more research is needed to confirm the findings, the results "suggest that a multifeatured smartphone application may have significant benefit to patients in continuing care for alcohol use disorders," the researchers wrote in the March 26 issue of the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

App support

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Typically, patients with alcoholism go through a 30-day intensive treatment at a residential facility, but oftentimes, they don't receive structured care after their treatment ends, said study researcher David H. Gustafson, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison's College of Engineering.

"A lot of people leave and say, 'Well, I'm cured,'" and don't continue with care outside the treatment facility, Gustafsonsaid.

However, an estimated 75 percent of people with alcohol abusedisorders drink in the first year after their treatment, the researchers said.

One of the main reasons the app may help patients is that it provides contact information for other people who are recovering from addiction, Gustafsonsaid.

"The ability to talk about their problems with others going through the same things they're going through made a big difference," Gustafsonsaid. "The panic button was used a lot more than I ever anticipated."

However, patients who used the app were just as likely to experience negative consequences from drinking, such as being arrested or losing a job, as those who did not use the app, the study found. This may have been because few people in the study experienced such negative consequences to begin with, so there was little potential for a decline, Gustafsonsaid.

Future research

"This study provides some pretty compelling data for programs that can be easily implemented and are low cost," and potentially effective for people with alcohol abuse disorders after treatment, said Sarah Bowen, an assistant professor at the University of Washington's department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

Such apps could be an alternative for people who cannot attend programs after their treatment — for instance, because they have transportation or child care issues, said Bowen, who was not involved in the study.

"It's another option for people after they come out of treatment, and we need to provide as many options as we can," Bowen said.

Because the study involved mainly men in their 30s and 40s at five treatment facilities, future studies of more diverse populations will be needed to confirm the findings, the researchers said. In addition, patients reported their own drinking behavior, which may not always be accurate.

Future studies are also needed to determine the reasons why the app appears to be helpful, Bowensaid.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.