How Dry Will It Get? New Climate Change Predictions

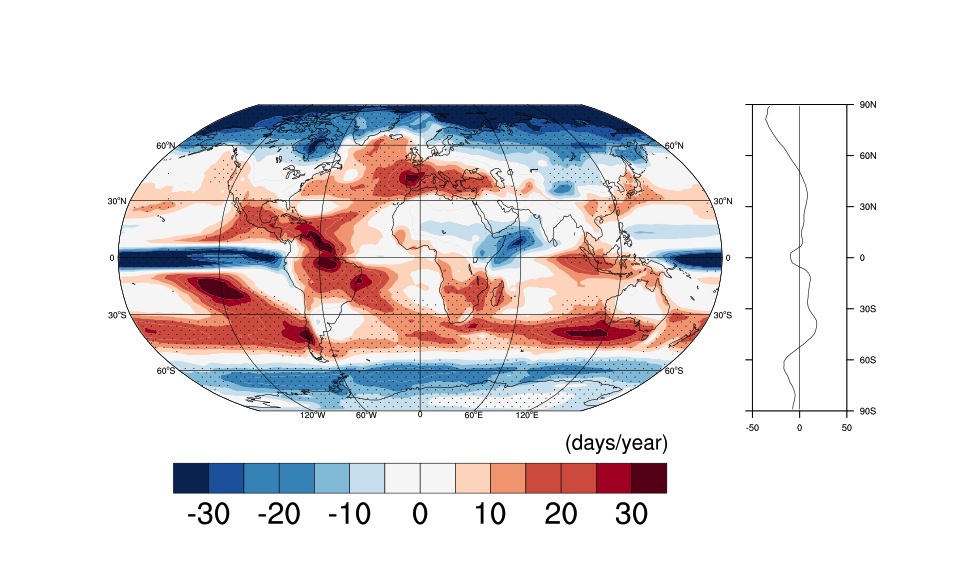

Global warming's crystal ball is clearing as climate models improve, and scientists now predict that some regions will see a month's less rain and snow by 2100.

The new rain and snow estimates indicate that subtropical spots — such as the Mediterranean, the Amazon, Central America and Indonesia — will undergo the biggest precipitation shifts in the coming decades. The number of dry days in these zones will rise by as many as 30 days per year, according to the study, published today (March 13) in the journal Scientific Reports.

"Looking at changes in the number of dry days per year is a new way of understanding how climate change will affect us that goes beyond just annual or seasonal mean precipitation changes, and allows us to better adapt to and mitigate the impacts of local hydrological changes," said Suraj Polade, a climate scientist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego and lead study author.

The findings also suggest a rising probability of droughts and floods in the near future as annual rainfall becomes more variable, the researchers said. [Weather vs. Climate Change: Test Yourself]

"Variability is going to play a big part in making things worse [as climate changes]," Polade told Live Science. "When you're increasing the variability of the climate, one year you can have a flood and the next year you can have a drought. You can also have an increase in extreme precipitation events, with a whole year's precipitation in just a few storms."

South Africa, Mexico and western Australia will go without rain for 15 to 20 more days per year, and California is likely to have five to 10 more dry days per year by the end of the century, the study found.

Some of the subtropical missing moisture will head north: The study predicts the Arctic will have 40 more wet days a year, but the South Pole will only get 10 more wet days per year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rerouting the weather

Why the shifts? Answers vary, but previous research has pointed the finger at changing storm tracks, particularly for tropical cyclones such as hurricanes and typhoons. Climate models suggest that midlatitude cyclones may shift north, while those that hit near the equator will likely stay their usual course.

There are also poleward shifts in the vast atmospheric patterns that control where rain falls. For example, the Hadley cell, the large-scale pattern of atmospheric circulation that transports heat from the tropics to the subtropics, has marched south during recent decades, moving the subtropical dry zone (a band that receives little rainfall) along with it. The northern and southern jet streams, which mark where cold and warm air meet, also seem to be creeping toward the poles. Their movement away from the equator suggests that the Earth's tropical zones are expanding, according to recent studies. The jet streams play an important role in moving moisture around the higher latitudes.

"We are looking at why this is happening," Polade said. "Earlier studies suggest that warmer regions will get wetter, while colder regions can get wetter or drier," he said. "The tropics are also getting wetter or drier, while the subtropics are drying."

The report relies on the latest global climate models (known as CMIP5), which predict future climate change under certain greenhouse-gas emissions scenarios. The study tested an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations to 950 parts per million by 2100, more than twice the current level. The number means there would be 950 molecules of carbon dioxide in the air per every million air molecules.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.