Strange State of Matter Found in Chicken's Eye

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

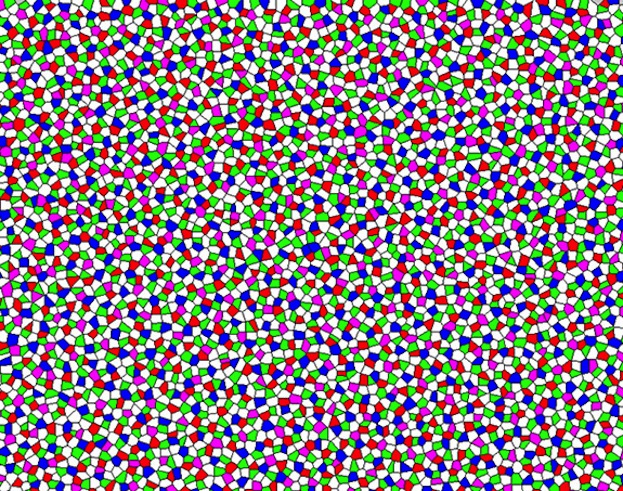

Never before seen in biology, a state of matter called "disordered hyperuniformity" has been discovered in the eye of a chicken.

This arrangement of particles appears disorganized over small distances but has a hidden order that allows material to behave like both a crystal and a liquid.

The discovery came as researchers were studying cones, tiny light-sensitive cells that allow for the perception of color, in the eyes of chickens. [The 9 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics]

For chickens and other birds that are most active during the daytime, these photoreceptors come in four different color varieties — violet, blue, green and red — and a fifth type for detecting light levels, researchers say. Each type of cone is a different size.

These cells are crammed into a single tissue layer on the retina. Many animals have cones arranged in an obvious pattern. Insect cones, for example, are laid out in a hexagonal scheme. The cones in chicken eyes, meanwhile, appear to be in disarray.

But researchers who created a computer model to mimic the arrangement of chicken cones discovered a surprisingly tidy configuration.

Around each cone is a so-called exclusion region that bars other cones of the same variety from getting too close. This means each cone type has its own uniform arrangement, but the five different patterns of the five different cone types are layered on top of each other in a disorderly way, the researchers say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Because the cones are of different sizes it's not easy for the system to go into a crystal or ordered state," study researcher Salvatore Torquato, a professor of chemistry at Princeton University, explained in a statement. "The system is frustrated from finding what might be the optimal solution, which would be the typical ordered arrangement. While the pattern must be disordered, it must also be as uniform as possible. Thus, disordered hyperuniformity is an excellent solution."

Materials in a state of disordered hyperuniformity are like crystals in that they keep the density of particles consistent across large spatial distances, Torquato and colleagues said. But these systems are also like liquids, because they have the same physical properties in all directions.

Researchers say this may be the first time disordered hyperuniformity has been observed in a biological system; previously it had only been seen in physical systems like liquid helium and simple plasmas.

For chicken eyes, the researchers speculate this cone arrangement allows the birds to sample incoming light evenly. Engineers may be able to take inspiration from disordered hyperuniformity in nature to create optical circuits and light detectors that are sensitive or resistant to certain light wavelengths, the researchers say. Their findings were detailed on Feb. 24 in the journal Physical Review E.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus