Can You Catch Obesity With That Head Cold?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Freelance writer Marlene Cimons is a former Washington reporter for the Los Angeles Times who specializes in science and medicine. She writes regularly for the National Science Foundation, Climate Nexus, Microbe Magazine, and the Washington Post health section, from which this article is adapted. Cimons contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

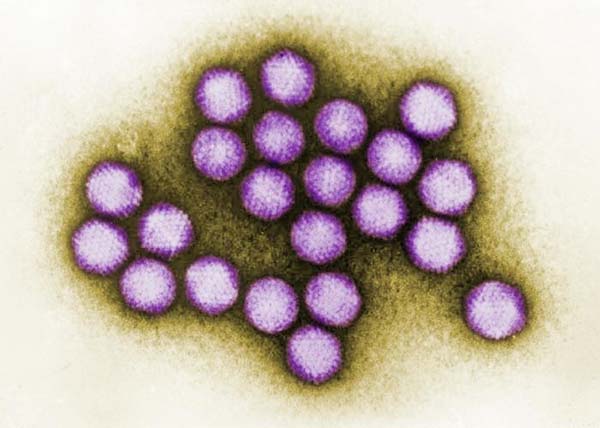

Some researchers believe that adenovirus 36, a cause of upper-respiratory infections, is a major factor in many cases of obesity.

Infection by this virus "is certainly not the cause of all obesity, but it will contribute to your weight,"" says Richard L. Atkinson, head of the Obetech Obesity Research Center in Richmond and a clinical professor of pathology at Virginia Commonwealth University. "It's a slow process that works by changing your metabolic rate. It takes a year or two to get really obese after you've been infected."

The virus prompts adult stem cells in fat tissue to make more fat cells, which store more fat, Atkinson says. "If you look at a given fat pad from an infected animal and compare it to an uninfected animal, it's got bigger fat cells and more of them," he says. "We can infect human adult stem cells in tissue culture, and even without differentiation agents added to the media, the cells differentiate into fat cells. Infected animals have larger fat pads than uninfected, with not only larger fat cells but more fat cells."

A number of recent studies in humans have shown that adenovirus 36 is associated with obesity especially in children.

These bolster earlier research showing that adenovirus 36 causes weight gain, and especially fat gain, in chickens, mice, rats and monkeys.

Paradoxically, while promoting weight gain, the virus also seems to lower cholesterol and triglycerides, raising intriguing questions about whether some component of the virus might prove valuable in developing a treatment for diabetes or high cholesterol.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While counterintuitive, since obesity is a risk factor for diabetes and heart disease, it is likely that the infection-fueled fat "finds a storage space in the adipose tissue and doesn't wander into your heart or muscles," says Nikhil Dhurandhar, a professor of health promotion at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University.

Dhurandhar and colleagues conducted a study published last year that followed 1,400 people: It found that those who tested positive for antibodies to the virus — meaning they had been infected at some point — gained significantly more body fat over a 10-year period than those who had not been infected.

Equally important, their blood-sugar levels were lower than those of the uninfected group. This does not mean that the virus might become a diabetes treatment. However, "perhaps we could identify a protein in the virus that is driving this, and develop drugs based on its action," Dhurandhar says.

Atkinson has developed an experimental vaccine against the virus, but he says it is years away from becoming available. "We have done some animal testing to show that the vaccine produces an antibody response, but more work in animals is necessary," he says.

Since the virus disappears from the body in about a month, "once a person becomes fat, he or she is no longer infectious to others and you don't have to worry about them," Atkinson says. "So, if you don't want to get infected, the best thing to do is wash your hands frequently, don't rub your nose, and avoid skinny people with colds."

The author's most recent Op-Ed was "Frailty Is a Medical Condition, Not an Inevitable Result of Aging." This article is adapted from "Virus Linked to Obesity," which appeared in the Washington Post. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus