Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

LOS ANGELES — Scientists have finally identified a new species of megamouth shark that prowled the oceans about 23 million years ago, nearly 50 years after the first teeth were discovered and then forgotten.

The ancient shark likely prowled both deep and shallow waters for plankton and fish, using its massive mouth to filter food.

"It was a species that was known to be a new species for a long time," said study co-author Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago. "But no one had taken a serious look at it," said Shimada, who described the new species here at the 73rd annual meeting of the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology. [8 Weird Facts About Sharks]

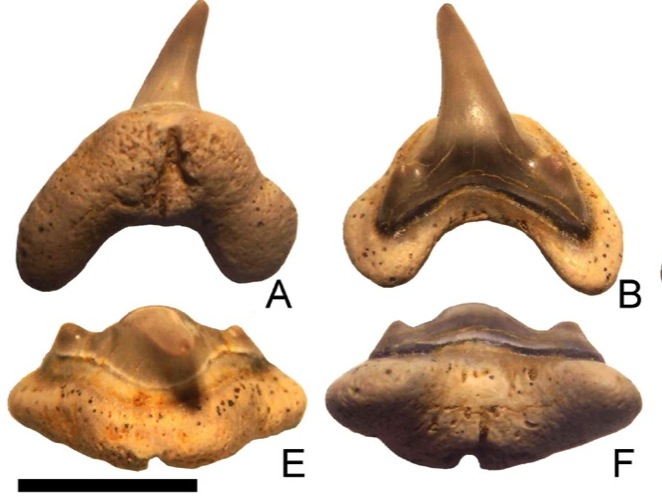

Shark teeth

Scientists first found shark teeth from the species in the 1960s, but at the time, there were no similar living creatures, so scientists didn't quite know what to make of the find. Over time, researchers turned up hundreds of similar teeth along the coast of California and Oregon. All the specimens were tossed in a drawer and forgotten in the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum and a few other California museums.

Then in 1976, scientists discovered the modern megamouth shark, dubbed Megachasma pelagios, which feeds exclusively on shrimplike creatures called plankton. The sharks use their mammoth mouths to engulf plankton-filled water, forcing the water through gills equipped with a filtering apparatus called gill rakers, which direct plankton into the digestive track.

The monster beast is also a vertical migrator, meaning the shark lurks in the deep ocean during the day, but comes up to the shallow surface waters chasing plankton swarms at night, Shimada said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Revisiting a shark

When Shimada came across the shark teeth at the Los Angeles County Museum, he was told that other scientists were studying them. But it turned out those scientists weren't actively working on the species.

Shimada contacted those scientists, Douglas Long of the California Academy of Sciences and Bruce Welton of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, and persuaded them to take a second look with him.

The team found the ancient creature was related to M. pelagios. But unlike the modern shark, it had slightly longer, pointier teeth.

"That suggests that they probably had a wider food selection," Shimada told LiveScience. "They could have probably eaten plankton, but they were also probably feeding on fish."

The team determined the ancient creature would've sported a slightly longer, less-wide snout than the modern megamouth shark. The extinct creature also likely grew to an average of 20 feet (6 meters), but the biggest megamouth individuals might have been nearly 27 feet (8 m) long, not much different from their modern relatives.

Because the teeth were found in both deep-ocean and near-shore marine sediments, the extinct monster probably had already begun to migrate between the deep and shallow oceans in search of food.

It's still not clear what caused the sharks to evolve to have wider mouths and adopt an exclusive filter feeding strategy, Shimada said.

Scientists haven't officially named the new species yet, but the genus will be called Megachasma, Shimada said.

The findings will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus