Why MERS is Not the New SARS

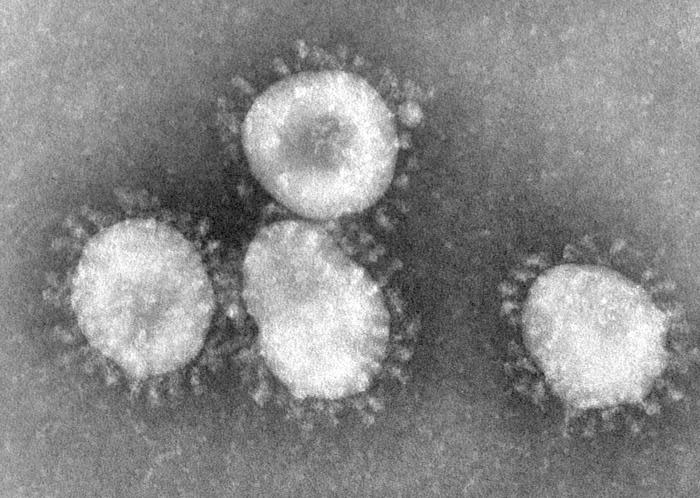

The new virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) has been compared to that of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) — the viruses belong to the same family, and are particularly deadly to infected people — however, the two conditions have some important differences, a new study says.

While MERS appears to be more deadly in those it infects, it also seems to be less contagious than SARS, the researchers said.

The evidence so far also suggests it's unlikely that MERS will follow a similar path to SARS, the researchers said.

Both MERS and SARS belong to a family of viruses called coronaviruses. SARS was first reported in Asia in 2002, and in less than a year, infected more than 8,000 people around the world, about 10 percent of whom died. MERS first appeared in Saudi Arabia in September last year, and has since infected 90 people and caused 45 deaths.

The new study is the largest to date on MERS, examining information from 47 people with the condition. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

The majority of infections have been in Saudi Arabia, although some infected people lived in or traveled to Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Among people admitted to the hospital with MERS, the most common symptoms were fever (98 percent), chills (87 percent), cough (83 percent) and shortness of breath (72 percent). Some patients also reported gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea and vomiting.

Unlike SARS, which tended to affect younger and healthier people, MERS appears to mainly infect people with underlying chronic conditions. Ninety-six percent of people with MERS in the study had a chronic condition such as diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease or kidney disease.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In those it does infect, MERS progresses rapidly, leading to death a week earlier, on average, compared with SARS, the researchers said. Sixty percent of people with chronic illnesses who contracted MERS died, compared with just 1 percent of people with chronic illnesses who contracted SARS.

The high death rate seen with MERS (50 percent) may be because researchers are, so far, only picking up the very severe cases of illness. Many more people may have caught MERS, but do not show symptoms, the researchers said.

The researchers said rapid and accurate tests to diagnose the disease are urgently needed. And more studies are needed to determine the scope of the outbreak, as well as risk factors for infection, and factors that might predict which patients are most likely to die from the infection, the researchers said.

The study is published today (July 26) in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com .

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus