Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

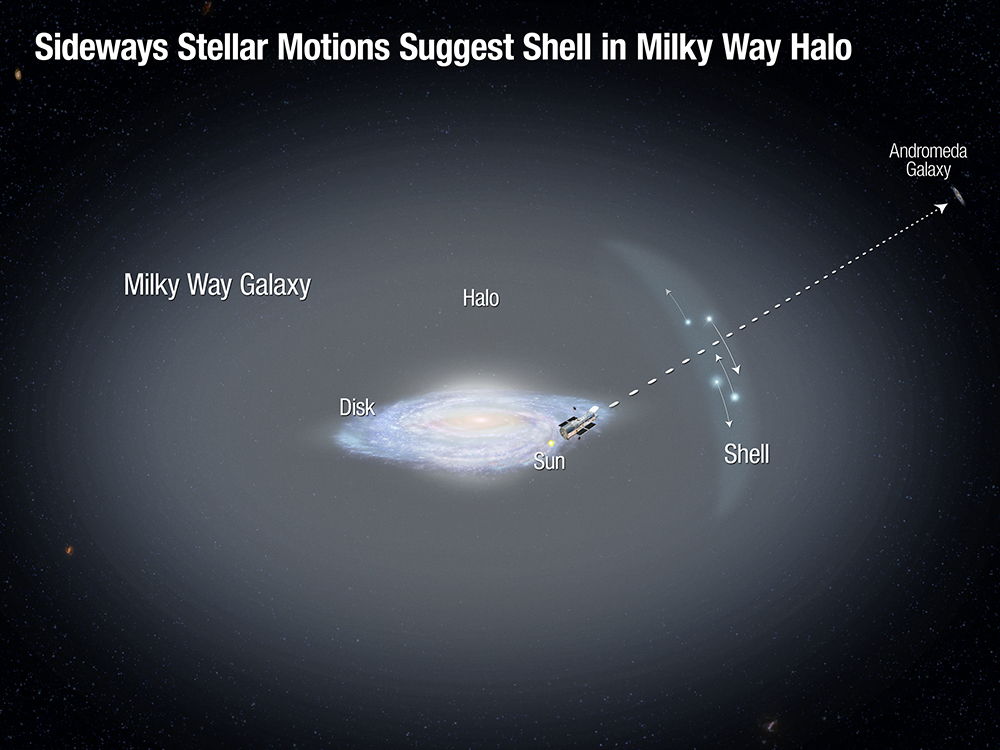

The Milky Way's far outer reaches may harbor a shell of stars left over from a long-ago act of galactic cannibalism, a new study suggests.

The finding supports the idea that our Milky Way has continued to grow over the eons by gobbling up smaller satellite galaxies, researchers said. And the results may help astronomers better understand how mass is distributed throughout the galaxy, which could shed light on the mysterious dark matter that's thought to make up more than 80 percent of all matter in the universe.

In the new study, scientists used NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to precisely measure the motion of 13 stars in the Milky Way's ancient outer halo, about 80,000 light-years from the galactic center. They picked the stars out of seven years' worth of archival Hubble observations, which were acquired when the telescope was staring at the neighboring Andromeda galaxy.

Identifying the handful of far-flung Milky Way residents was no picnic, as each Hubble image contained more than 100,000 stars. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy]

"It was like finding needles in a haystack," co-author Roeland van der Marel, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in a statement.

The team found that the outer halo stars had a surprisingly high level of sideways, or tangential, motion relative to their radial motion (which describes movement toward or away from the Milky Way's core).

The existence of a shell structure — which can be created by the accretion of a satellite galaxy — could explain the halo stars' unexpected motion, researchers said, noting that shell-like features have been observed around other galaxies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What may be happening is that the stars are moving quite slowly because they are at the apocenter, the farthest point in their orbit about the hub of our Milky Way," lead author Alis Deason, of the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement. "The slowdown creates a pileup of stars as they loop around in their path and travel back towards the galaxy. So their in and out or radial motion decreases compared with their sideways or tangential motion."

Deason and her colleagues plan to study more outer halo stars to determine if the shell at 80,000 light-years really does exist. Their overall goals are to gain a better understanding of the Milky Way's formation and evolution, and to calculate an accurate mass for the galaxy.

This latter aim has proven elusive to date.

"Until now, what we have been missing is the stars’ tangential motion, which is a key component," Deason said. "The tangential motion will allow us to better measure the total mass distribution of the galaxy, which is dominated by dark matter. By studying the mass distribution, we can see whether it follows the same distribution as predicted in theories of structure formation."

The new study has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus