Scientists have discovered neurons in mice that fire in response to gentle, stroking touch.

The neurons, described in the Jan. 31 issue of the journal Nature, may explain why animals, from rats to cats to humans, enjoy grooming each other and being stroked.

The new discovery could also lead one day to a kind of massage pill, said Alan Basbaum, a neuroscientist at the University of California San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

"It's a nice piece of work. It's technically elegant, and it does have interesting implications," Basbaum told LiveScience. If these neurons can be activated by certain chemicals, "you could generate drugs that make you feel good."

Soothing touch

Most people, along with many other mammals, enjoy being gently stroked, but why people enjoy massage isn't clear, said study co-author David Anderson, a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology.

But because mammals do a lot of social grooming, being wired to find such touch pleasurable would be important in strengthening ties among group members, Anderson told LiveScience. Past work has identified the neurons specific to itch, but massage has proved more elusive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

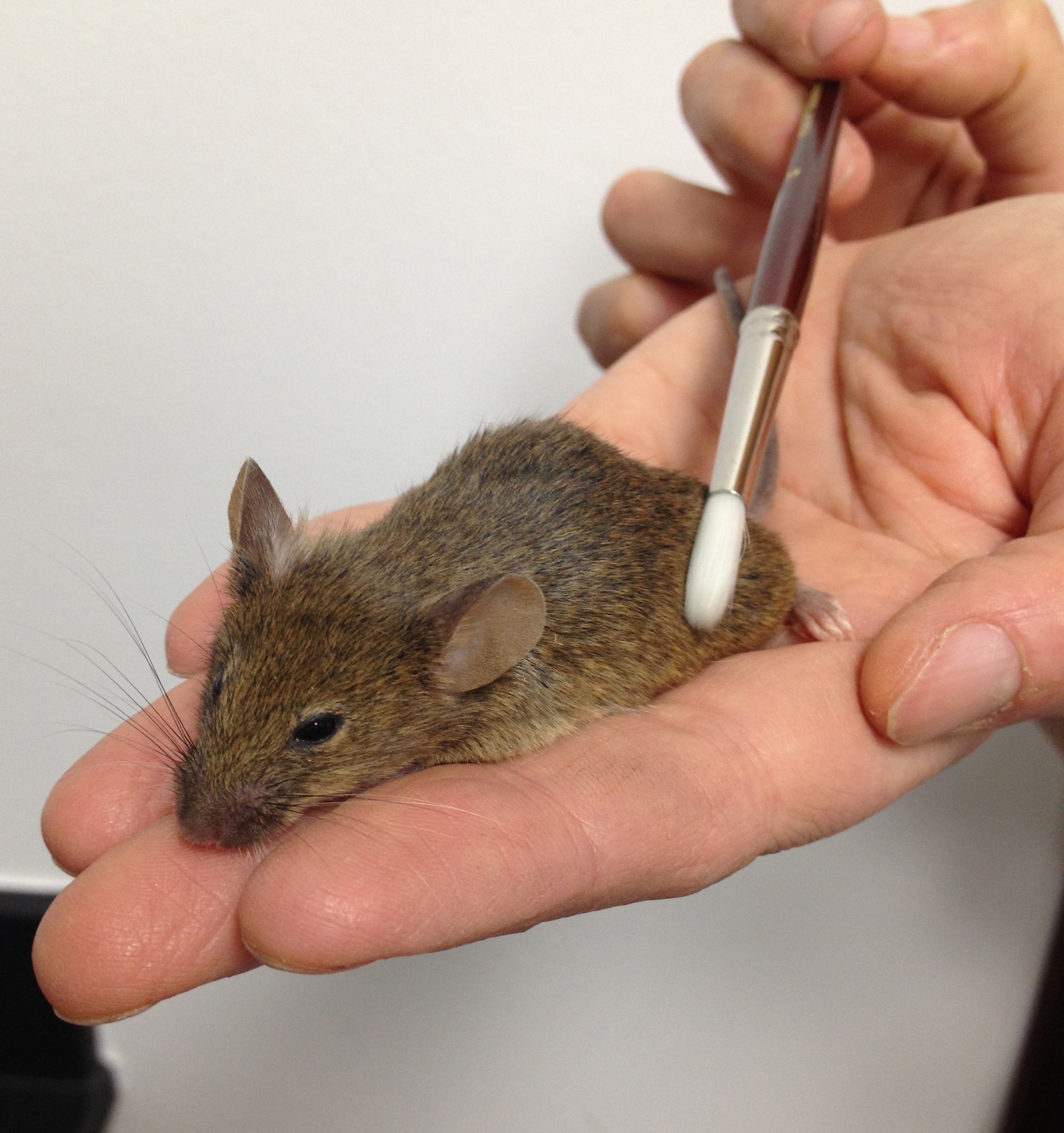

Scientists had pinpointed a specific group of neurons (also called nerve cells) that lurked beneath the skin and were connected to neurons around the spinal cord, but it wasn't clear exactly what these cells near the skin did. To find out, Anderson and his colleagues used genetic engineering to make these neurons in mice glow when they fired (or became active).

Then the researchers subjected the mice to gentle stroking with a paintbrush, pinching or poking sensations. The neurons only fired when the mice got the soft, massage-like touch. [10 Odd Facts About the Brain]

"It is brushing with a gentle pressure component," Anderson said. "It's not like a deep tissue massage, but it's also not a very light, superficial stroke."

That feels good

Next, researchers created a method to chemically activate these neurons. Scientists put 18 mice into a box that had a central room, with doors to a room on the left and the right. When the mice were in one side of the box, the researchers activated the animals' neurons chemically and let the mice hang out for about an hour. The scientists repeated this procedure a few times.

A group of 30 control mice were left in the room without chemical enhancement.

Afterwards, researchers let all of the mice loose in the box with the doors open. Control mice spent roughly equal amounts of time exploring each room, but the mice that received the chemical massage spent more time in the room where their stroking neurons had been activated.

That the mice spent more time in the "chemical massage parlor" than the other sides of the room suggests they associated this area with a pleasant experience.

While no one knows if humans have these exact same nerve cells, "there is evidence from other labs that says that humans have neurons in their skin that respond to gentle touch," Anderson said.

The findings may help explain why animals spend so much time grooming each other: it probably feels good. But the new discovery may not explain why Fluffy the cat licks herself incessantly, because it's not clear that self-grooming can activate the same neurons, Anderson said.

Video credit: Nature Video

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.