Fructose Sugar Tells the Brain To Keep Eating

Foods that contain the sugar fructose may cause people to gain more weight than foods that contain the sugar glucose, a new study suggests.

Consuming glucose signals to the brain that you've eaten, and thus satiates appetite. By contrast, eating fructose does not, said the researchers, from Yale University School of Medicine.

The results suggest that the pervasiveness of high-fructose corn syrup in Western diets — the sugar is found in many processed foods and beverages, including juice and soda — may contribute to the obesity epidemic, experts say.

But other experts argue that the findings should be interpreted with caution. The study examined the brain's response to pure fructose and pure glucose. However, processed foods generally contain a combination of fructose and glucose (high-fructose corn syrup, for example, contains about 55 percent fructose and 45 percent glucose.) For this reason, it's not possible to say how the results would play out in the real world, said Terry Davidson, director of the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience at American University in Washington, D.C.

"I'm not necessarily sure that you would have seen similar effects," if the study included high-fructose corn syrup instead of pure fructose, Davidson said. [See 5 Ways Obesity Affects the Brain.]

In addition, the study only looked at the sugars' effects on the brain, and did not examine whether people really do eat more food after consuming fructose than they would after eating glucose. So more research is needed to better understand the role fructose plays in obesity, Dr. Jonathan Purnell, a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

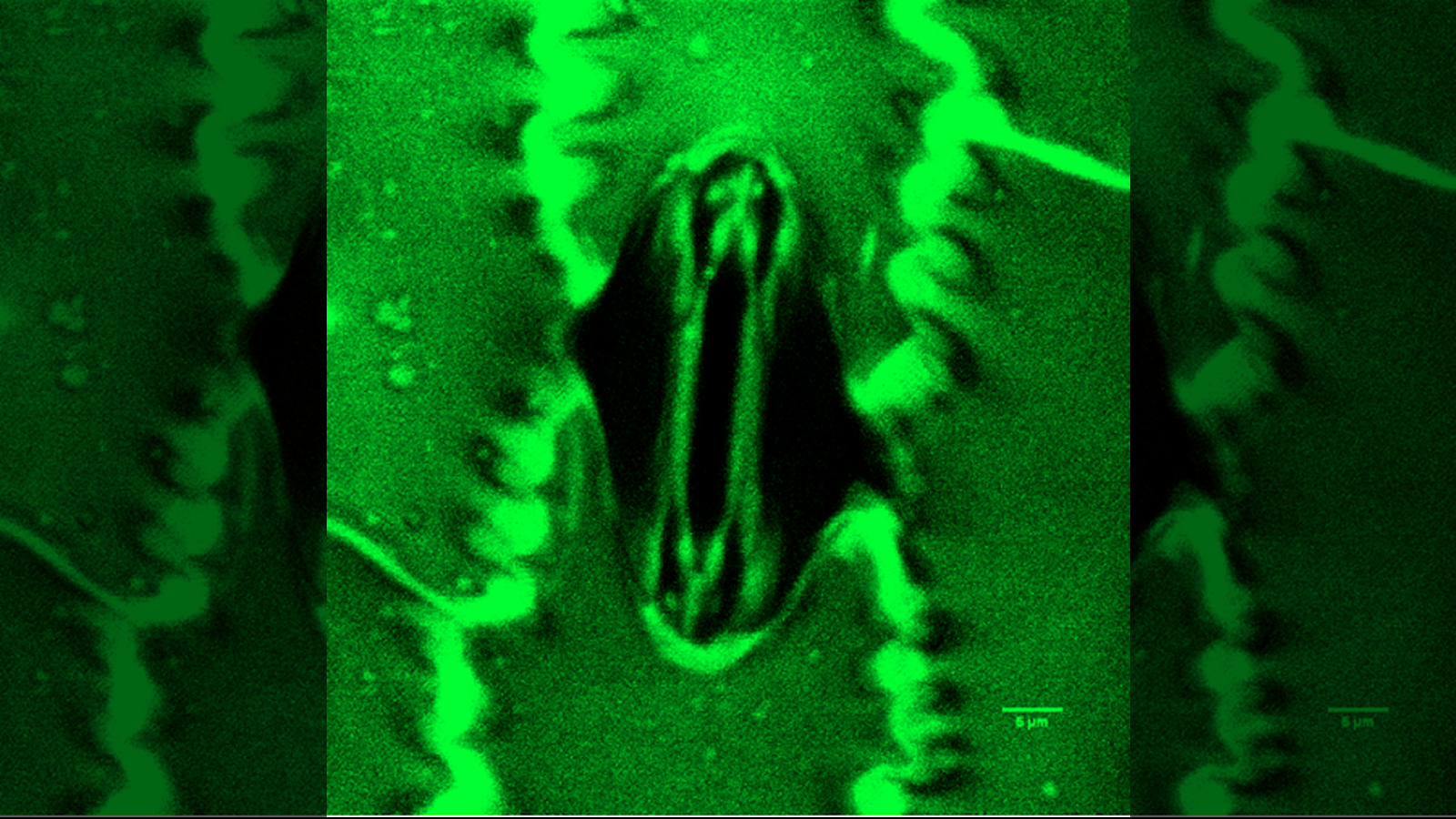

The study involved 20 normal-weight people who had their brains scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) before and after they drank water sweetened with either fructose or glucose.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When people consumed glucose, the researchers saw a decrease in activity in the hypothalamus, a brain region that regulates appetite and rewards. However, they did not see this decrease after fructose consumption.

The study and editorial were published Jan. 1 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Pass it on: The brain may react differently to the sugars fructose and glucose.

Follow Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner, or MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus