Fit for a King: Largest Egyptian Sarcophagus Identified

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The largest ancient Egyptian sarcophagus has been identified in a tomb in Egypt's Valley of the Kings, say archaeologists who are re-assembling the giant box that was reduced to fragments more than 3,000 years ago.

Made of red granite, the royal sarcophagus was built for Merneptah, an Egyptian pharaoh who lived more than 3,200 years ago. A warrior king, he defeated the Libyans and a group called the "Sea Peoples" in a great battle.

He also waged a campaign in the Levant attacking, among others, a group he called "Israel" (the first mention of the people). When he died, his mummy was enclosed in a series of four stone sarcophagi, one nestled within the other.

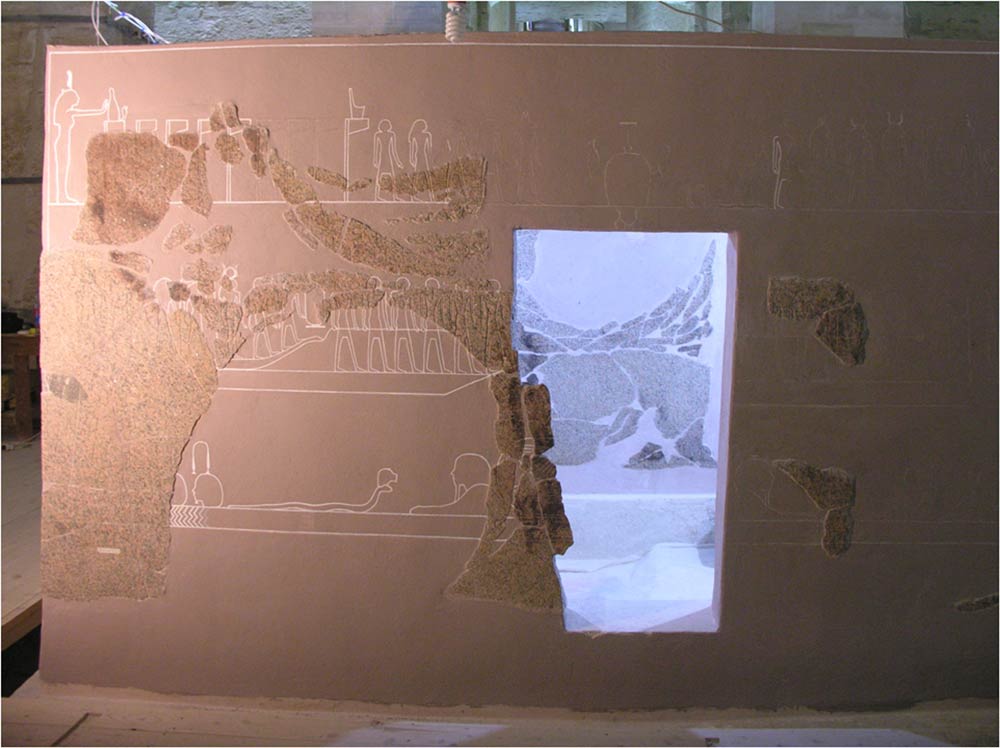

Archaeologists are re-assembling the outermost of these nested sarcophagi, its size dwarfing the researchers working on it. It is more than 13 feet (4 meters) long, 7 feet (2.3 m) wide and towers more than 8 feet (2.5 m) above the ground. It was originally quite colorful and has a lid that is still intact. [See Photos of Pharaoh's Sarcophagus]

"This as far as I know is about the largest of any of the royal sarcophagi," said project director Edwin Brock, a research associate at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, in an interview with LiveScience.

Brock explained the four sarcophagi would probably have been brought inside the tomb already nested together, with the king's mummy inside.

Holes in the entrance shaft to the tomb indicate a pulley system of sorts, with ropes and wooden beams, used to bring the sarcophagi in. When the workers got to the burial chamber they found they couldn't get the sarcophagi box through the door. Ultimately, they had to destroy the chamber's door jams and build new ones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I always like to wonder about the conversation that might have taken place between the tomb builders and the people from the quarry," said Brock in a presentation he gave recently at an Egyptology symposium in Toronto. "This study has shown a lot of interesting little human aspects about ancient Egypt [that] perhaps makes them look less godlike."

When he first examined fragments from Merneptah's tomb in the 1980s, they were "piled up in no particular order" in a side chamber. Even when put together, the fragments made up just one-third of the box, meaning researchers had to reconstruct the rest.

Brock's efforts got a boost with the launch of a full reconstruction project (affiliated with the Royal Ontario Museum) that started in March 2011. (Merneptah's tomb has been recently re-opened to the public.)

The four sarcophagi

Not only was the pharaoh's outer sarcophagus huge but the fact that he used four of them, made of stone, is unusual. "Merneptah's unique in having been provided with four stone sarcophagi to enclose his mummified coffined remains," said Brock in his presentation. [The 10 Weirdest Ways We Deal With the Dead]

Within the outer sarcophagus was a second granite sarcophagus box with a cartouche-shaped oval lid that depicts Merneptah. Within that was a third sarcophagus that was taken out and reused in antiquity by another ruler named Psusennes I. Within this was a fourth sarcophagus, made of travertine (a form of limestone), that originally held the mummy of Merneptah.

Only a few fragments of this last box survive today; the mummy itself was reburied in antiquity after the tomb was robbed more than 3,000 years ago. It was after this robbery that the outer sarcophagus box, and the second box within it, were broken apart (the lids for both boxes being kept intact). They were destroyed not only for their parts but also to help get at the third box (that was reused by Psusennes).

Fire was used in breaking apart the outer sarcophagus box.

"Scorch marks, spalling [splinters] and circular cracking on various locations of the interior and exterior of the box attest to the use of fire to heat parts of the box, followed by rapid cooling with water to weaken the granite," writes Brock in his symposium abstract, adding that dolerite hammer stones also appear to have been used.

Why so big?

Why Merneptah built himself such a giant sarcophagus is unknown. Other pharaohs used multiple sarcophagi, although none, it appears, with an outer box as big as this.

Brock points out that Merneptah's father, Ramesses II, and grandfather, Seti I, both great builders, were apparently each buried in one travertine sarcophagus.

The decorations on Merneptah's different sarcophagi offer a clue as to why he built four of them. They contain illustrations "from two compositions that describe the sun god's journey at night, one is called the 'Book of Gates' and one is called the 'Amduat,'" Brock said. These books are divided into 12 sections, or "hours."

He notes that the same hours tend to be repeated on the box and lids of Merneptah's sarcophagi. One motif the king appears particularly fond of is the opening scenes of the "Book of Gates," including one depicting a realm that exists before the sun god enters the netherworld, according to Egyptologist Erik Hornung's book "The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife" (Cornell University Press, 1999, translation from German). "Upon his entry into the realm of the dead, the sun god is greeted not by individual deities but by the collective of the dead, who are designated the 'gods of the west’ and located in the western mountain range," Hornung writes.

For the king repeating scenes like this over and over may have been important, it’s "as though they're trying to enclose the [king's] body with these magical shells that have power of resurrection," Brock said.

The research was presented at a Toronto symposium that ran from Nov. 30 to Dec. 2 and was organized by the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities and the Royal Ontario Museum's Friends of Ancient Egypt.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus