Scientists See Deep Inside Human Brain

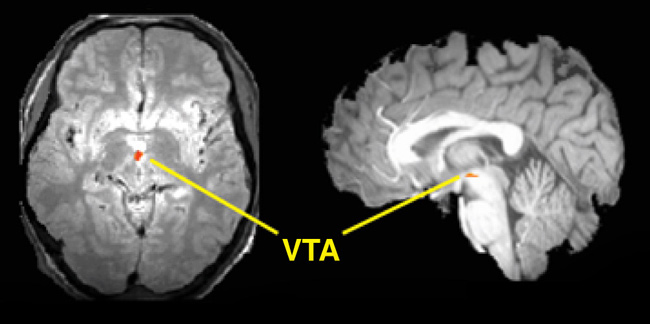

The human brainstem, the most primitive area of our brains, has been notoriously difficult to image because of its small size.

Now researchers have devised a new experimental technique that produces some of the best functional images ever taken of the human brainstem.

The scientists used functional magnetic resonance imaging to study brainstem activity in dehydrated humans. The reported their results in Feb. 28 edition of the journal Science.

The subjects were participating in classical conditioning experiments in which they were presented with a visual clue, then, at varying intervals, given a drink. The researchers were able to track changes in blood flow in areas of the brainstem associated with enhanced activity of the brain chemical dopamine — as the person experienced either pleasure or disappointment at receiving or not receiving the reward.

"For a long time, scientists have tried looking at this area of the brain and have been unsuccessful — it's just too small," said Kimberlee D'Ardenne, a doctoral student in chemistry at Princeton University and the lead author on the paper.

Until now, scientists wanting to use brain scans to study brain chemicals like dopamine were relegated to watching its effects in other more accessible parts of the brain, like the prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum. However, this was downstream of its source, and therefore possibly much less accurate, D'Ardenne said. "We wanted to try because the brainstem is so important to activities in the rest of the brain," said D'Ardenne. "We believe it could be a key to understanding all kinds of important behavior."

The brainstem, a tiny, root-shaped structure, is the lower part of the brain and sits atop the spinal cord. The area controls brain functions necessary for survival, such as breathing, digestion, heart rate, blood pressure and arousal. This structure also serves as the home base for the brain chemicals, also known as neuromodulators, such as dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine. The chemicals spring forth into other brain regions from there, zipping along routes called axons.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team's experiments confirmed results already seen in animal studies. Blood flow increased in dopamine centers of the brainstem when test subjects were happily surprised with a reward. However, there was no activity when participants received less than what they expected, a finding that is different from the results of previous studies looking farther downstream.

"We are just at the beginning of understanding these crucial pathways," D'Ardenne said. "But it gives us a hint about what is possible to know."

For the research, D'Ardenne collaborated with Jonathan Cohen, co-director of the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, and Samuel McClure and Leigh Nystrom, other institute scientists.

- Body Parts Quiz

- Video: Here's To Your Brain

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind