Mass-Production Sends Robot Insects Flying

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

A new technique inspired by elegant pop-up books and origami will soon allow clones of robotic insects to be mass-produced by the sheet.

Devised by engineers at Harvard University, the ingenious layering and folding process enables the rapid fabrication of not just microrobots, but a broad range of electromechanical devices. The new technique replaces a tedious and time-consuming manual process for creating such devices.

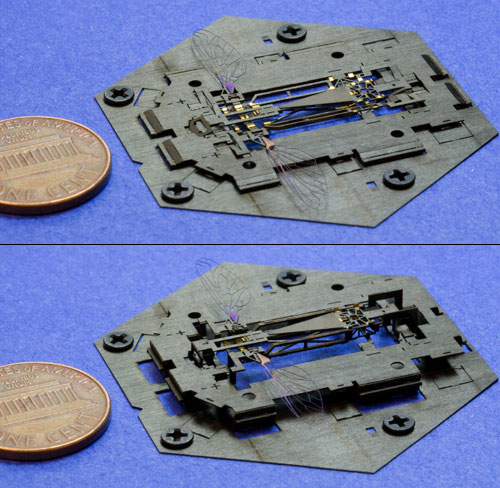

For prototypes, engineers laminated together layers of carbon fiber, Kapton (a plastic film), titanium, brass, ceramic, and adhesive sheets in a complex, laser-cut design. The structure incorporates flexible hinges that allow the 3-D product — just 0.1 inch (2.4 millimeters) tall — to assemble in one movement, like a pop-up book.

The entire product is approximately the size of a U.S. quarter, and dozens of these microrobots could be fabricated in parallel on a single sheet.

"This takes what is a craft, an artisanal process, and transforms it for automated mass production," researcher Pratheev Sreetharan, who co-developed the technique with J. Peter Whitney, said. Both are graduate students at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

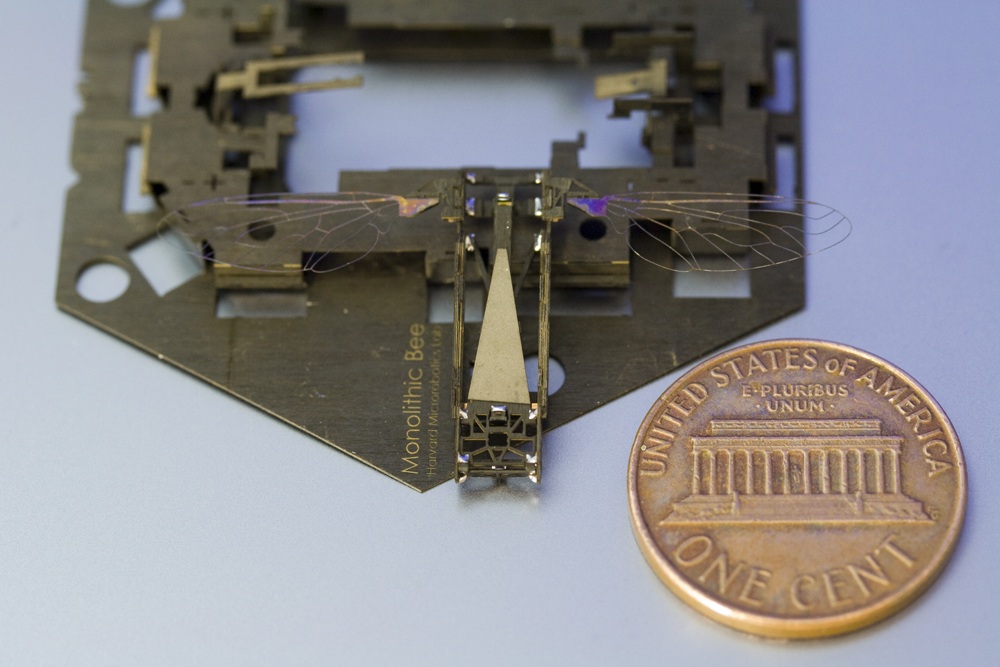

Sreetharan, Whitney, and their colleagues in the Harvard Microrobotics Laboratory have been working for years to build bio-inspired, bee-sized robots that can fly and behave autonomously as a colony. Appropriate materials, hardware, control systems, and fabrication techniques did not exist prior to the RoboBees project, so each must be invented, developed, and integrated by a diverse team of researchers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The RoboBees project is supported by the National Science Foundations' Expeditions in Computing program, as well as the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard.

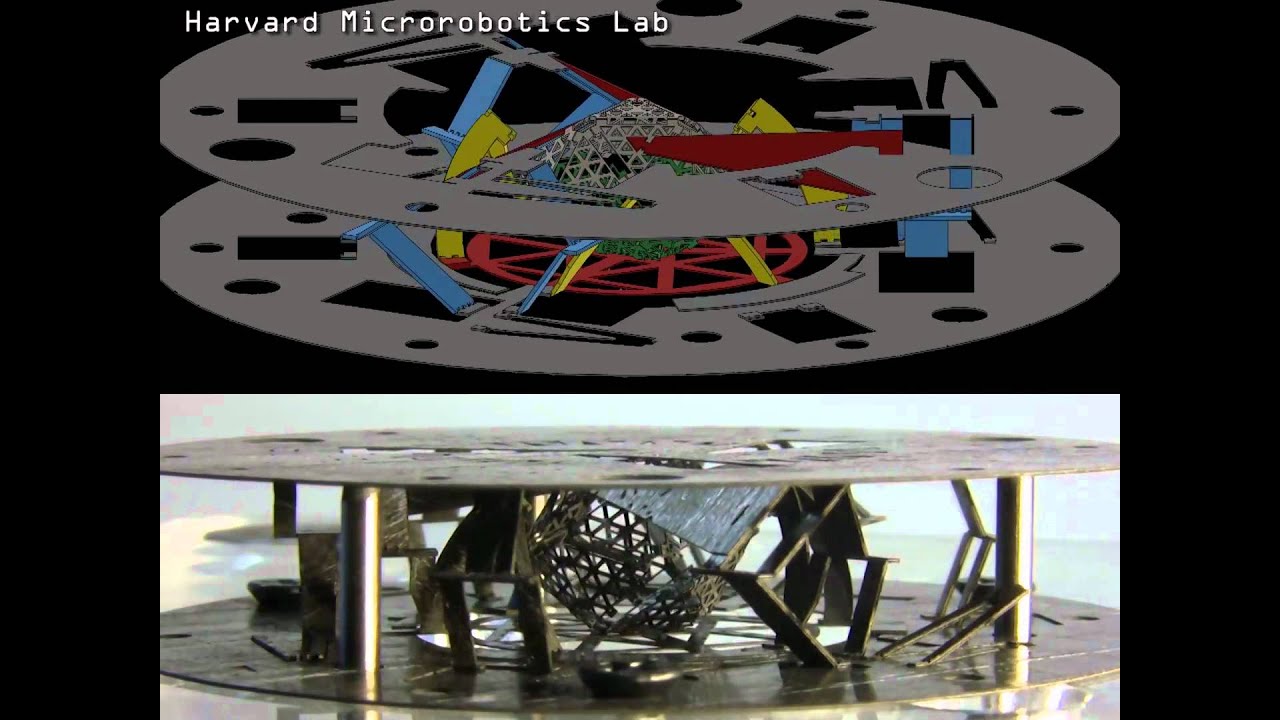

"The ability to incorporate any type and number of material layers, along with integrated electronics, means that we can generate full systems in any three-dimensional shape," principal investigator Rob Wood, an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering at Harvard, said. "We've also demonstrated that we can create self-assembling devices by including pre-stressed materials."

Printed bot boards

Moreover, the layering process builds on the manufacturing process currently used to make printed circuit boards, which means that the tools for creating large sheets of pop-up devices are common and abundant. It also means that the integration of electrical components is a natural extension of the fabrication process — particularly important for projects like RoboBees where the devices are constrained in their size and weight.

"In a larger device, you can take a robot leg, for example, open it up, and just bolt in circuit boards," explains Sreetharan. Our devices are "so small that we don't get to do that." Pointing to the carbon-fiber box truss that constitutes the pop-up bee's body frame, Sreetharan said, "Now, I can put chips all over that. I can build in sensors and control actuators."

The implications of this novel fabrication strategy go far beyond the micro-air vehicles. The same mass-production technique could be used for high-power switches, optical systems, and any other tightly integrated electromechanical devices that have parts on the scale of micrometers to centimeters.

Ultimately, with such an efficient technique, tiny robots might soon be built by only slightly bigger ones.

See a flat sheet pop up into an icosahedron below.

Editor's Note: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus