9 Famous Art Forgers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Forgery Artists

"To trick the art world has been the primary motivation of nearly all of history's known forgers," writes Noah Charney, a professor and author who specializes in art history and crime, in text for an exhibit focused on one such forger who appears to break this rule.

The subject of a University of Cincinnati exhibit, Mark Landis, is unusual in this regard. Landis says he was first motivated to donate a fake drawing to a museum by a desire to please his mother and honor his father, then became addicted to the VIP treatment he received from museum staff. "Landis is more of a footnote to the history of art forgery, warranting his own chapter, rather than part of the larger continuum of famous forgers who work for revenge and money," Charney writes.

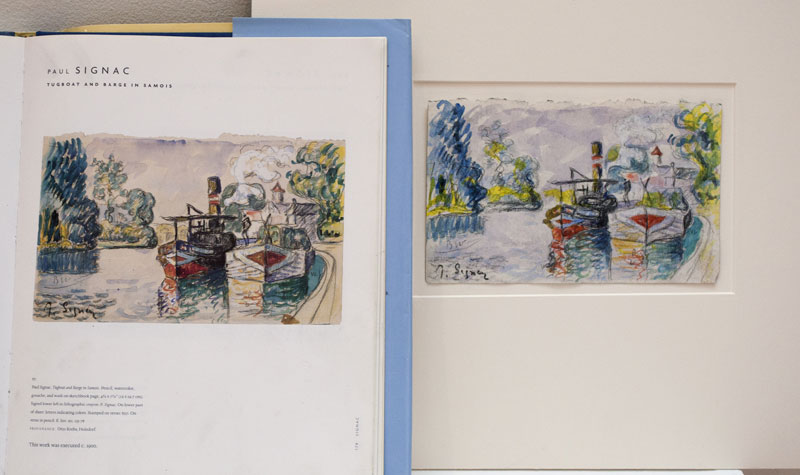

Here's a look at some of the most intriguing art forgers, including Landis. (Above, on the right, a copy Landis created of a watercolor by the French painter Paul Signac, using an image from a catalogue on the left.)

Mark Landis (b. 1955)

Mark Landis is believed to have presented more than 100 forged works of art to museums across 20 U.S. states. To make these donations seem authentic, Landis used aliases and even dressed as a Jesuit priest. He says he was first motivated by a desire to please his mother and honor his father, then became addicted to the VIP treatment he received from museum staff. He never received money or tax benefits. The work above is a copy Landis made of one of Picasso's paintings, based on the image in the catalog to the left, and donated to a museum in Florida.

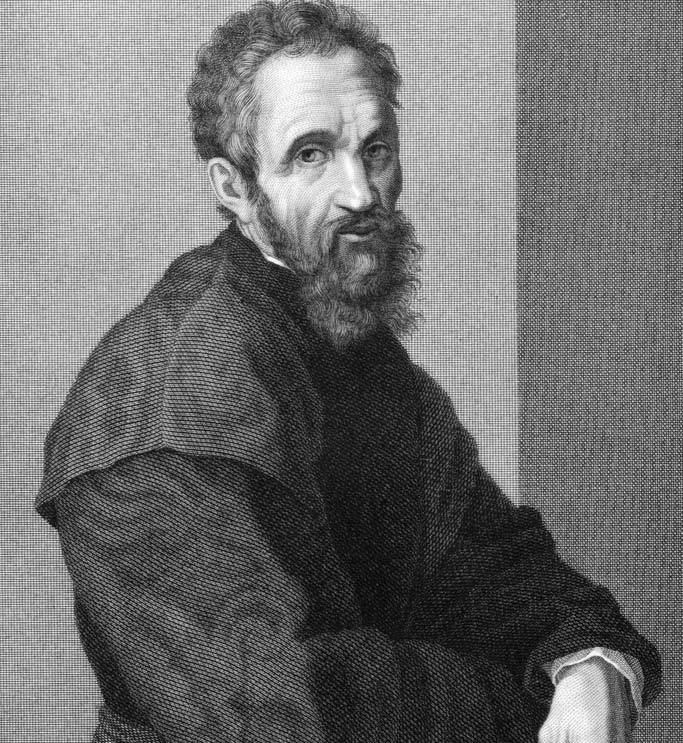

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564)

Yes, this is the Michelangelo of the Sistine Chapel. He began his sculpting career by passing off his early marble sculpture, Sleeping Eros as an ancient Roman statue in order to fetch a much better price. With help from a dealer, Michelangelo damaged and buried the sculpture in the dealer's yard, in order to "discover" it as an ancient sculpture, according to Charney.

Icilio Federico Joni (1866-1946)

Joni spent many years as a successful art forger, fooling the art historian Bernard Berenson. When Berenson realized he had purchased fakes, he traveled to Italy to meet Joni, expressing his admiration. It is said that Berenson sold several of Joni's works as originals afterward, while keeping a few of the pieces in his collection as reminders. In 1936, Joni published a memoir titled "Affairs of a Painter," in spite of antique dealers' attempts to bribe him into not to publishing, according to Charney.

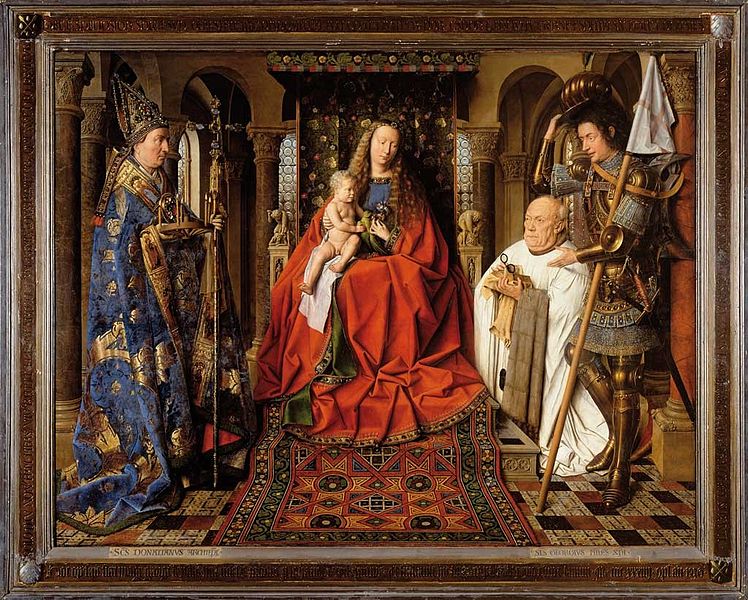

William Sykes (18th century)

Forgery isn't just about making a convincing copy. During the 18th century, William Sykes convinced the Duke of Devonshire that an anonymous painting of an unidentified saint was actually a portrait by Jan van Eyck, whose works claimed the highest prices at auction of any artist at the time, according to Charney.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

(Shown here, a 1434 van Eyck painting called "Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele," a renowned example of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting.)

Han van Meegeren (1889-1947)

The Dutch forger's work was uncovered after World War II, when a previously unknown Johannes Vermeer painting turned up in a Nazi leader's collection. The painting was traced back to Van Meegeren, who had been dismissed as an original artist; he was charged with selling a Dutch national treasure and collaborating with the enemy. Facing the possibility of the death penalty, Van Meegeren confessed forging the painting, but the work was so good he had to prove his guilt by forging another painting while in prison, according to Charney.

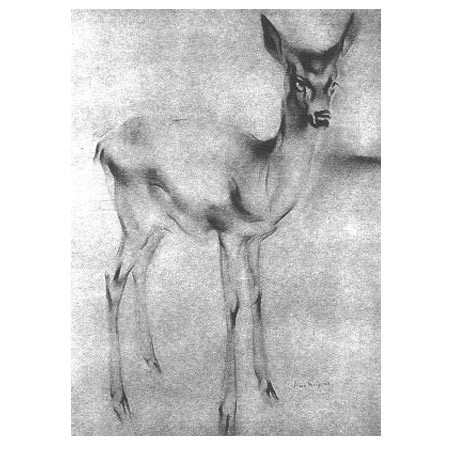

(Shown here, one of van Meegeren's best-known original drawings, "The Fawn," one of Princess Juliana of the Netherlands' deer.)

Tom Keating (1917-1984)

This British artist, too, turned to forgery after the art world dismissed his original works. He created more than 2,000 forgeries of works from more than 100 artists. After being caught and serving time, Keating starred in a popular British TV series, in which he taught aspiring painters how to copy famous works. In 1984, when he died, Christie's auctioned 204 of his works, according to Charney.

(Shown here, a reproduction of Vermeer's "Girl with a glass" painting.)

John Myatt (b. 1945)

Myatt collaborated with his dealer, John Drewe, forging work by Chagall, Giacometti and others to match fake records for the work, which Drewe created. These were inserted into real archives, so scholars would later "discover" them. Although the con has been uncovered, along with 60 of the fakes, the potential for damage lingers, because 140 remain unfound, creating the potential for scholars to mistake them for the real thing. After serving his prison sentence, Myatt helped track down other forgers. He now sells "genuine fakes" bearing his own signature, and George Clooney is reportedly interested in turning Myatt's life story into a film.

Eric Hebborn (1934-1996)

A graduate of London's Royal Academy of Art, Hebborn began making forgeries after a famous London art dealer bought a real drawing from him, then sold it for many times more. Hebborn claimed to have produced approximately 1,000 forgeries of drawings by Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, Raphael, Anthony van Dyck, Nicolas Poussin, and 18th-century painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, among many others. These were sold by noted auction houses to numerous prestigious collections. He wrote two memoirs of his career, including one that explained his tricks for aspiring forgers. In 1996, he was murdered in Rome, according to Charney.

Shaun Greenhalgh (b. 1961)

Convicted of forgery in November 2008, Greenhalgh and his octogenarian parents were involved in the most wide-reaching forgery campaign of all time. Greenhalgh created works of astounding diversity, from 20th-century British sculpture to an Egyptian statue purportedly from 1350 B.C., fooling Christie's, Sotheby's and The British Museum, as well as other illustrious victims. The Greenhalghs were caught when a British Museum expert noted that Assyrian sculptural relief tablets, supposedly created in Mesopotamia in 700 B.C., contained misspellings in cuneiform, the ancient writing, according to Charney.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus