Largest Molecules Yet Behave Like Waves in Quantum Double-Slit Experiment

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

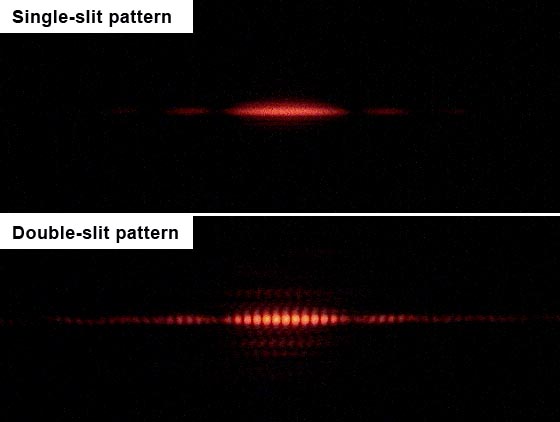

One of the most famous experiments in quantum physics, which first showed how particles can bizarrely behave like waves, has now been carried out on the largest molecules ever.

Researchers have sent molecules containing either 58 or 114 atoms through the so-called "double-slit experiment," showing that they cause an interference pattern that can only be explained if the particles act like waves of water, rather than tiny marbles.

Researchers said it wasn't a foregone conclusion that such large particles would act this way.

"In a way it's a little bit surprising, because these are highly complex and also flexible molecules; they change their shape while they're flying through the apparatus," said Markus Arndt of the University of Vienna in Austria, a co-leader of the project. "If you talk to the community, maybe 50 percent would say this is normal because it's quantum physics, and the other 50 percent would really scratch their heads because it's quantum physics."

Indeed, the double-slit experiment, one of the foundations of quantum physics, was voted the "most beautiful experiment" ever in a 2002 poll of Physics World readers.

Beautiful experiment

The experiment was first carried out in the early 1800s by English scientist Thomas Young in an effort to find out if light is a wave or a collection of tiny particles. [Graphic: Nature's Tiniest Particles Explained]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Young sent a beam of light through a plate with two parallel slits cut out of it. When the light hit a screen behind the plate, it produced a pattern of dark and bright bands that only makes sense if light is a wave, with crests (high points) and troughs (low points). When the crests of two waves overlap, they create an especially bright patch, but when a crest and a trough overlap, they cancel each other out, leaving a dark space.

The results of the experiment showed that light behaves like a wave, and disproved the popular idea of the 17th and 18th centuries that light was made of tiny discrete particles. However, in 1905, Einstein's explanation of the photoelectric effect showed that in addition to behaving like waves, light also acts like particles, leading to the current notion of light's "wave-particle duality."

The double-slit experiment upturned physics again in 1961 when German physicist Claus Jönsson showed that when electrons passed through the two slits, they, too, produced an interference pattern.

The results were shocking, because if electrons were individual particles as was thought, then they wouldn't produce such a pattern at all — rather they would create two bright lines where they had impacted the screen after passing through one or the other of the slits (about half would pass through one slit, and the rest through the other, thereby building up the two lines after a number of particles had passed through).

This groundbreaking experiment befuddled and irked physicists, who knew from other tests that electrons also behave like particles. Ultimately, it showed that they are, somehow, both.

"Seeing the two-slit experiment is like watching a total solar eclipse for the first time: A primitive thrill passes through you and the little hairs on your arms stand up," astronomer Alison Campbell of Scotland's St. Andrews University wrote to Physics World. "You think this particle-wave thing is really true and the foundations of your knowledge shift and sway."

Wave of probability

If electrons were waves, they would travel through both slits at once, whereas particles must travel through one or the other slit, it was thought. And even electrons slowed down to the point where only one passes through the experiment at a time still manage to interfere with each other. How can this be?

It took the modern theory of quantum mechanics to explain the results by suggesting that particles exist in a state of uncertainty, rather than at a specific time and place, until we observe them, forcing them to choose. Thus, the particles traveling through the plate don't have to select slit A or slit B; in effect, they travel through both.

This is one of the ways particles in the tiny quantum world behave oddly, diverging from the understandable macroscopic, classical world of people and buildings and trees. But scientists have wondered where the boundary between the two is, and if one even exists.

"Some physicists argue there must be an objective threshold between quantum and classical physics," Arndt told LiveScience. "That's puzzling also."

If there is a boundary, the researchers' 58- and 114-atom molecules, made of links of carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen, are pushing it.

"We're still in the strange situation that if you believe that quantum physics is everything, then all of us are somehow quantum-connected, which is hard to believe. But it's also hard to believe that quantum physics ends at some point. That's why groups like us are trying to increase the complexity [of our molecules] to see if there is a threshold at some point."

The results of the research, led by Thomas Juffmann, also of the University of Vienna, were published online March 25 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. For more science news, follow LiveScience on twitter @livescience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus