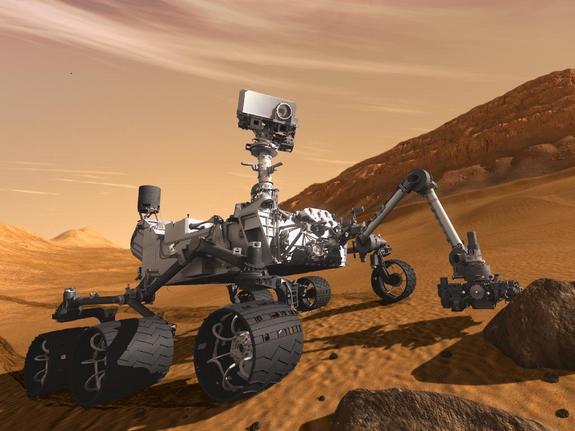

NASA's Curiosity rover will launch on Saturday (Nov. 26) toward a frigid and dry Mars, but the robot will likely spend much of its time staring deep into the Red Planet's warmer, wetter past, scientists say.

Curiosity, also known as the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), aims to assess whether Mars is, or ever was, capable of supporting microbial life. The $2.5-billion rover will work hard to reconstruct and investigate ancient environments, because Martian life likely had a better shot at gaining a foothold long ago, researchers said.

"We've learned that Mars is a dynamic planet," Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA's Mars exploration program, told reporters today (Nov. 21). "We've learned that it has a history where it was warm and wet at the same time that life started here on Earth."

A changing Mars

Most scientists hunting for signs of life beyond Earth have focused on wet environments, because life on our planet is reliant on water. By this measure, modern Mars would seem a poor candidate, because its surface is mostly cold and dry today (although water ice does lurk beneath the red dirt).

But this was not always so. Many ancient riverbeds snake around the Red Planet's surface, and most scientists think they were carved by liquid water in the distant past. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Various Mars orbiters and rovers have also spotted lots of clays on Mars, suggesting that water once persisted on the surface for extended periods of time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Clay minerals form from long-term chemical interaction of water with rock," said Bethany Ehlmann of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech in Pasadena, Calif.

This wet period petered out around 3 billion years ago, and Mars became the dry, dusty planet we see today. The MSL team hopes Curiosity can help them understand more about this dramatic transition.

Going to Gale Crater

Curiosity is about the size of a Mini Cooper and weighs 1 ton — five times more than each of its Mars rover predecessors, the golf-cart-size twins Spirit and Opportunity.

The huge rover will use 10 different science instruments to search for organics — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it — and characterize the Red Planet environment and how it has changed over time.

Curiosity is slated to touch down at a 90-mile-wide (150 kilometers) crater called Gale in August 2012. Clays and sulfates, which also betray past water activity, are plentiful at Gale, and a mysterious 3-mile-high (5 km) mountain rises from the crater's center.

The mountain is composed of sedimentary rock, meaning it grew from sediment deposited over billions of years. So Gale should be a great place to investigate Mars' past and present habitability, as well as the transition from wet to dry that occurred so long ago, researchers said.

"In one location, we can drive the rover through all these successive different environments and sample these various periods in the history of Mars," said MSL project scientist John Grotzinger of Caltech.

While Curiosity is tackling the Martian-life issue, MSL is not a life-detection mission. So even if microbial Martians are squirming about in the soils of Gale Crater, the rover is not likely to detect them.

"It can look at organics and characterize them, and make you more interested in Mars and what secrets it might hold," Meyer said. "But unless you're extremely lucky, it's not going to tell you whether or not you found evidence of life."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.