Image Gallery: Stunning Dual-Sex Animals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Stunning creatures

Some creatures can't pick sides, like this half-male, half-female leopard lacewing butterfly. Dual-sex animals like this one, called gynandromorphs, are also found in birds and crustaceans. This butterfly emerged from its chrysalis at Iowa State University's Reiman Gardens in 2008. Half of its body is male, with a male's orange, black and white wing. The other half is female, with a female's paler wing.

One in 100,000+

In almost nine years, Reiman Gardens has received about 163,116 pupae to populate its butterfly wing. But this leopard lacewing is the only gynandromorph butterfly to ever emerge. Gynandromorphs likely go unnoticed in species in which males and females look alike, so it is difficult to estimate how frequently they occur.

Male-Female Bee

Gynandromorphs aren't limited to butterflies and moths. This carpenter bee has the dark, larger body of a female on one side, as well as a smaller, lighter male side. It resides in a collection of the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History. The date and place it was found were not recorded.

The comparison

The gynandromorph bee sits between a light male bee on the left, and a dark, larger female bee on the right. If a particular genetic error occurs during the first cell division after fertilization, it can create a bilateral gynandromorph, like the bee in the middle. When this happens, each sex claims half of the insect: wings, genitalia, body size, coloration and other sex-related features. The same error can also occur later in development and result in a mosaic gynandromorph, which has patches of male cells and patches of female cells.

A lucky find

James Adams, a biology professor, found this gynandromorph tiger swallowtail at Pigeon Mountain in Georgia. But the location doesn’t really matter, he said: "You never go out to look for those because they are genetic anomalies. You happen upon them."

Barely visible

Not all gynandromorphs make for dramatic specimens. James Adams found this forest tent caterpillar moth on the wall of a gas station underneath a light. Often, gynandromorphs go unnoticed because the differences between their male and female parts aren't that dramatic. A line down the middle of the moth's body marks the division between the lighter, somewhat fluffier male side from the female side, which is longer, causing the abdomen to curl.

A literary bug

The author Vladimir Nabokov was an unofficial curator of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) for Harvard's research collection, and, in his autobiography, he recounts losing a prized gynandromorph as a child when his governess sat on his collection: "… A precious gynandromorph, left side male, right side female, whose abdomen could not be traced and whose wings had come off, was lost forever: one might re-attach the wings, but one could not prove that all four belong to that headless thorax on its bent pin." Shown above is an unrelated gynandromorph blue morpho butterfly featured in "The Rarest of the Rare: Stories Behind the Treasures at the Harvard Museum of Natural History" (Harper-collins Publishers, 2004).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Blue morpho butterflies

The more brilliant blue male morpho butterfly is shown above, and the female below. Both are on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History to show the difference between males and females – called sexual dimorphism – in the same species of butterfly.

An unexpected arrival

In January, this odd cardinal showed up at Larry Ammann's backyard feeder in Texas. (The red side is male.) Ammann, a wildlife photographer, had never seen anything like it. He and the biologists he consulted concluded it was likely part male, part female — a gynandromorph. Eventually, the bird was chased away by other cardinals.

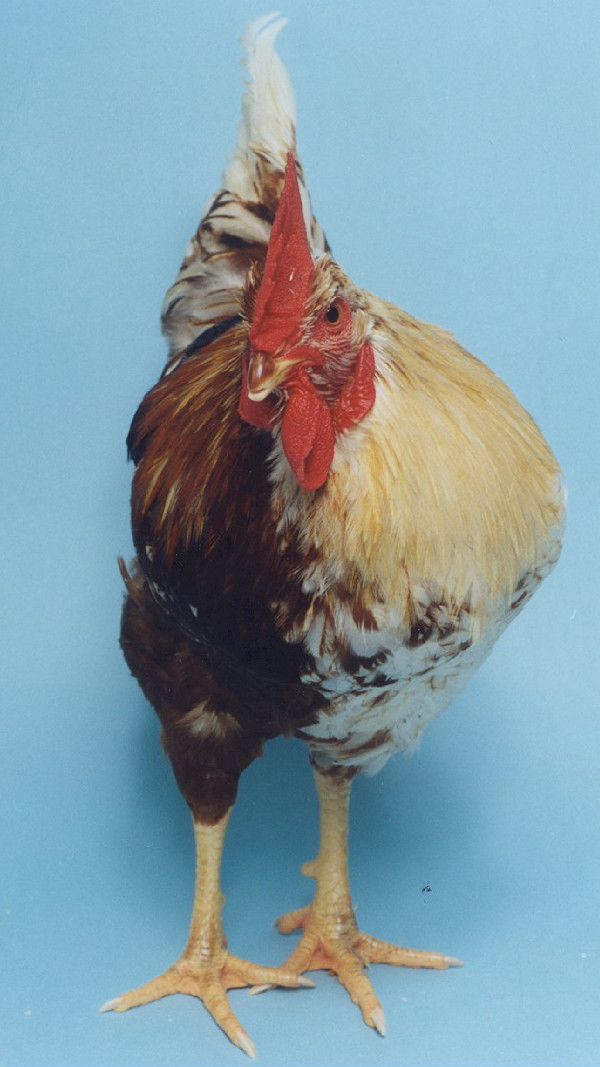

Funky chicken

This rare chicken has a brown hen side with a small wattle and slight build, while its masculine side has white plumage, with a larger wattle, breast musculature, a heavier bone structure and a leg spur, all as a cockerel should.

Related: Sex-change chicken: Gertie the hen becomes Bertie the cockerel

Identity issues?

Three gynandromorph chickens like this one showed scientists that most cells on a gynandromorph bird's male side have male sex chromosomes, while most of the cells on its female side have female sex chromosomes. By studying the chickens, scientists found evidence that individual cells play an important role in determining sex differences for birds. (Hormones play a crucial role in determine sex characteristics in humans, which may explain why gynandromorphs do not appear to exist among us.)

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus