Hens Feel for Their Chicks' Discomfort

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A worried mother is often called a mother hen, and new research is showing how true this expression may be. When her chicks are in distress, a hen will react physically, showing empathy.

"It's very fascinating to find out about the emotional lives of animals, but also it's highly relevant for animal welfare," said researcher Joanne Edgar of the University of Bristol, in southern England. The finding is important in farming or laboratory situations, where birds and other animals are often exposed to the pain and distress of their co-habitants in tight quarters. If they feel empathy toward their injured coop-mates, they could be put under extra stress.

To simulate this stress, the researchers exposed hens and chicks to puffs of air (as from a keyboard-cleaning canister), causing the birds mild distress without harm or pain.

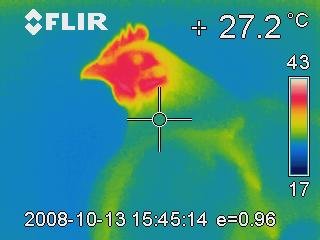

The hens, which were separated from the chicks but could see, smell and hear them, paid more attention to their surroundings when the puff of air was directed at them. But when it was directed at their chicks, the mama birds responded more intensely with a stress response equivalent to fight-or-flight behavior: The hens' heart rates increased and their external temperatures changed (even though the chicks weren't making distress calls, ruling out the possibility that this was a protective-mom response).

They also emitted a "maternal vocalization" call, which is used to call their chicks back to them, Edgar told LiveScience. "It also enhances memory formation of the chicks. Then they know what to do in these circumstances if it ever arises again," she said.

Primatologist Frans de Waal of Emory University, who wasn't involved in the study, called the findings very interesting. "Not only is the mother hen emotionally affected, she also starts calling, which seems an 'other-oriented' response. She is trying to change the situation," de Waal said.

Edgar said she is currently studying whether this same reaction happens in response to other adult chickens, and seeing what actions the hens might be reacting to. Also, the team is seeing whether this reaction could be called an emotion, by determining if it can be classified as an "adverse" or protective reaction by the hen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most empathy studies in animals have been conducted in mammals, assuming that such a response evolved with parental care of children, an obligate behavior in mammals. This new study, along with others, suggests empathy might have evolved from an older common ancestor – possibly a reptile, de Waal told LiveScience in an e-mail. Empathy could be over 200 million years old, he wrote.

The study was be published in Today's (March 8) issue of the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus