World's oldest DNA reveals secrets of lost Arctic ecosystem from 2 million years ago

Researchers have unearthed tiny fragments of DNA in the Arctic that were left by plants, microbes and animals that lived in a previously unknown ecosystem in Greenland.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have discovered tiny fragments of 2 million-year-old DNA trapped within frozen layers of Arctic sediment. The ancient genetic material, which is the oldest ever discovered, has provided a glimpse of a previously unknown ecosystem.

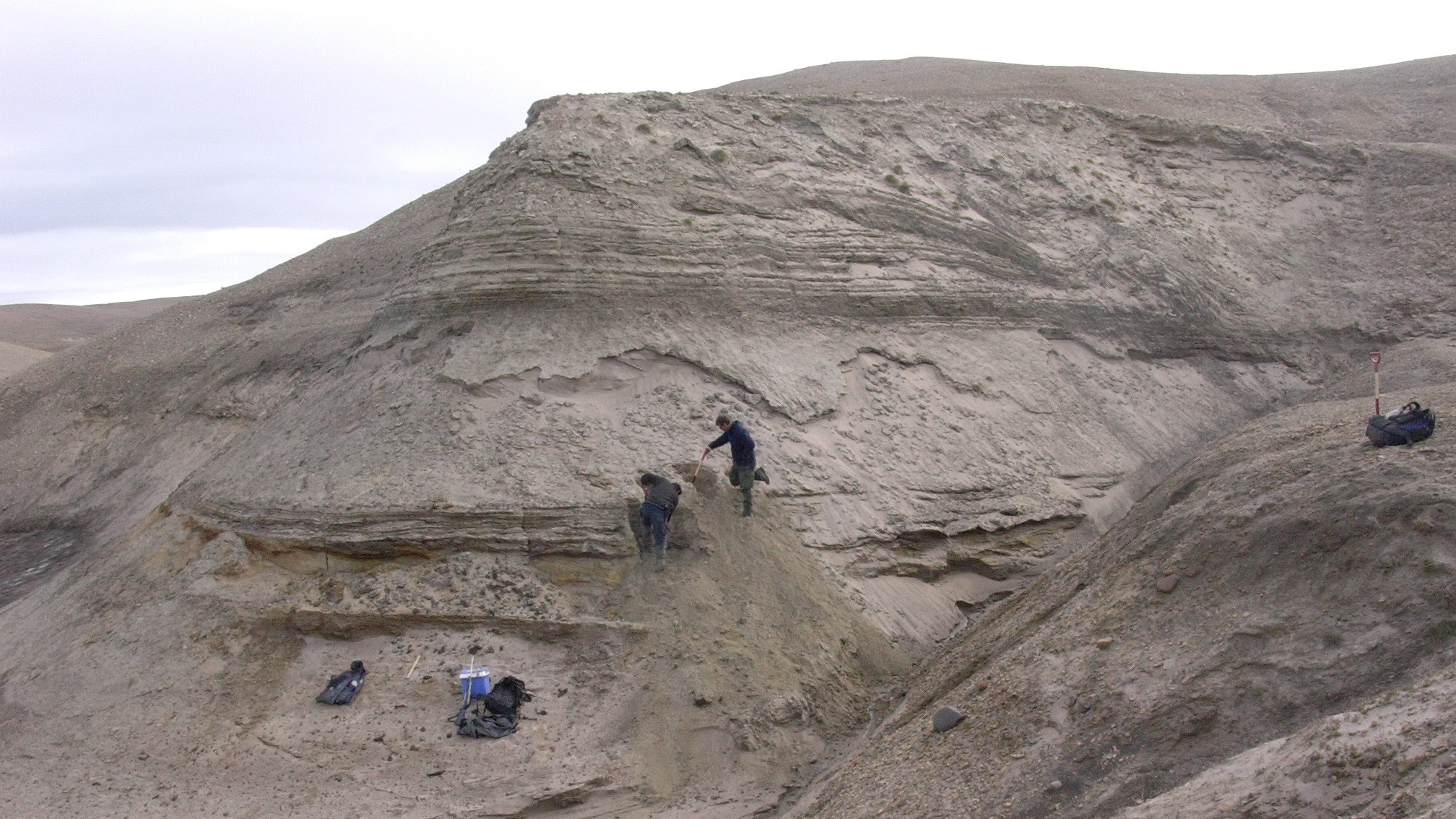

Since 2006, researchers have uncovered 41 samples of DNA within a 328-foot-deep (100 meters) slab of sediment at the Kap København Formation in northern Greenland. The genetic fragments, known as environmental DNA, were left by plants, animals and microbes that once lived in the area and have been perfectly preserved by permafrost and ice.

The previous oldest DNA sample ever found, which was revealed to the world in 2021, was retrieved from a 1.2 million-year-old mammoth bone in Siberia, researchers wrote in a statement.

In a new study, published Dec. 7 in the journal Nature, researchers isolated and analyzed the ancient DNA samples and compared them with known genome sequences to reveal what creatures left the DNA. The results paint a picture of an incredibly diverse ecosystem that included birds, reindeer, hares and, most surprisingly, mastodons, an extinct group of elephant relatives that were not previously known to have lived that far north.

"A new chapter spanning one million extra years of history has finally been opened and for the first time we can look directly at the DNA of a past ecosystem that far back in time," study lead author Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., said in the statement.

Related: Scientists discover 1 million-year-old DNA sample lurking beneath Antarctic seafloor

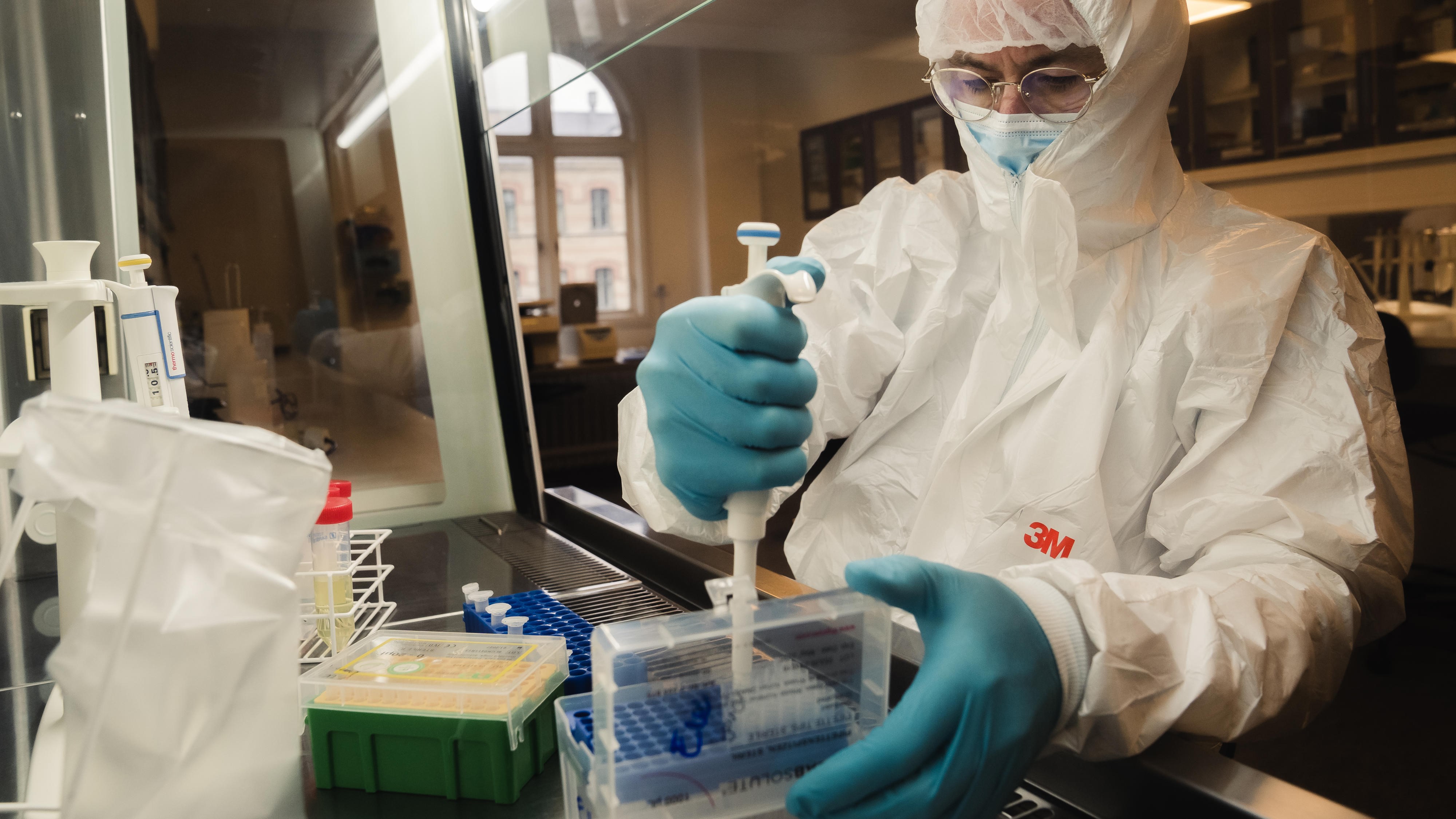

The DNA fragments were incredibly difficult to study. Each scrap of genetic material was only "a few millionths of a millimeter long," which made it hard to isolate the fragments from the sediment layer without completely breaking them, the researchers wrote in the statement. The collection of the sediment began in 2006, but before attempting to extract the DNA, the researchers decided to wait until more advanced technology was available.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It wasn't until a new generation of DNA extraction and sequencing equipment was developed that we've been able to locate and identify extremely small and damaged fragments of DNA in the sediment samples," study co-author Kurt Kjær, a paleogeologist and geneticist at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, said in the statement.

As well as a variety of animals, the DNA also revealed the presence of several species of trees, bacteria and fungi. Not all of the DNA samples could be matched with known species, suggesting that some could be new to science. However, almost all were identified to at least the correct genus.

The sediment layer excavated by the researchers accumulated during a 20,000-year period around 2 million years ago. During this time, the area was between 18 and 31 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 17 degrees Celsius) warmer than Greenland is today, the researchers wrote in the statement. This shows that entire ecosystems can rise and fall because of climatic changes, they added.

Related: World's oldest human DNA found in 800,000-year-old tooth of a cannibal

"The data suggests that more species can evolve and adapt to wildly varying temperatures than previously thought," study co-author Mikkel Pedersen, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Copenhagen, said in the statement. "But, crucially, these results show they need time to do this." Therefore, species at threat from current human-driven climate change are unlikely to be as successful because they will have much less time to adapt, he added.

The researchers will now try to build a more in-depth picture of the Kap København ecosystem by working out how the various species might have interacted with one another, according to the statement. The new findings could also shed more light on if and how DNA has changed over the last 2 million years, the team added.

Being able to locate, isolate and sequence such ancient DNA also provides hope that similarly ancient, or even older, genetic samples could be unearthed elsewhere around the globe.

"If we can begin to explore ancient DNA we may be able to gather ground-breaking information about the origin of many different species — perhaps even new knowledge about the first humans and their ancestors," Willerslev said. "The possibilities are endless."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus