There’s too much gold in the universe. No one knows where it came from.

Something is showering gold across the universe. But no one knows what it is.

Something is raining gold across the universe. But no one knows what it is.

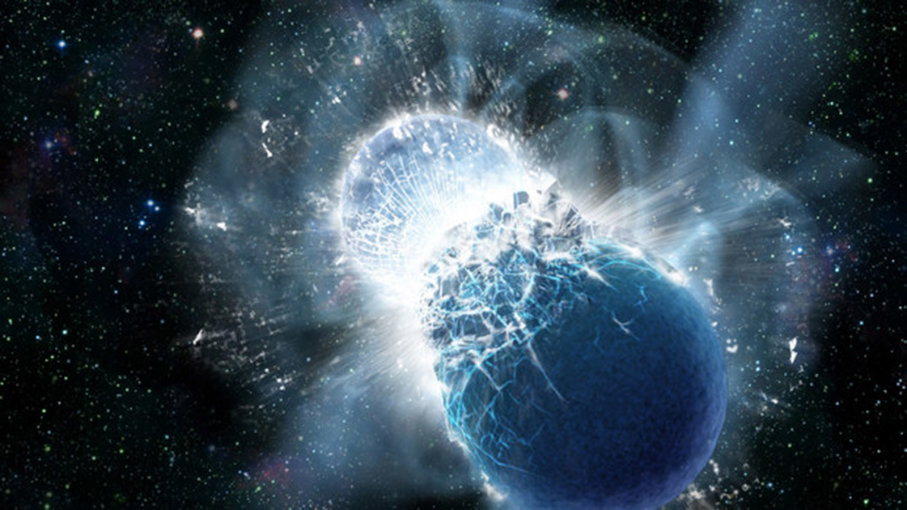

Here's the problem: Gold is an element, which means you can't make it through ordinary chemical reactions — though alchemists tried for centuries. To make the sparkly metal, you have to bind 79 protons and 118 neutrons together to form a single atomic nucleus. That's an intense nuclear fusion reaction. But such intense fusion doesn't happen frequently enough, at least not nearby, to make the giant trove of gold we find on Earth and elsewhere in the solar system. And a new study has found the most commonly-theorized origin of gold — collisions between neutron stars — can't explain gold's abundance either. So where's the gold coming from? There are some other possibilities, including supernovas so intense they turn a star inside out. Unfortunately, even such strange phenomena can't explain how blinged out the local universe is, the new study finds.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

Neutron star collisions build gold by briefly smashing protons and neutrons together into atomic nuclei, then spewing those newly-bound heavy nuclei across space. Regular supernovas can't explain the universe's gold because stars massive enough to fuse gold before they die -- which are rare -- become black holes when they explode, said Chiaki Kobayashi, an astrophysicist at the University of Hertfordshire in the United Kingdom and lead author of the new study. And, in a regular supernova, that gold gets sucked into the black hole.

So what about those odder, star-flipping supernovas? This type of star explosion, a so-called magneto-rotational supernova, is "a very rare supernova, spinning very fast," Kobayashi told Live Science.

During a magneto-rotational supernova, a dying star spins so fast and is wracked by such strong magnetic fields that it turns itself inside out as it explodes. As it dies, the star shoots white-hot jets of matter into space. And because the star has been turned inside out, its jets are chock full of gold nuclei. Stars that fuse gold at all are rare. Stars that fuse gold then spew it into space like this are even rarer.

But even neutron stars plus magneto-rotational supernovas together can't explain Earth's bonanza of gold, Kobayashi and her colleagues found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There's two stages to this question," she said. "Number one is: neutron star mergers are not enough. Number two: Even with the second source, we still can't explain the observed amount of gold."

Past studies were right that neutron star collisions release a shower of gold, she said. But those studies didn't account for the rarity of those collisions. It's hard to precisely estimate how often tiny neutron stars — themselves the ultra-dense remnants of ancient supernovas — slam together. But it's certainly not very common: Scientists have seen it happen only once. Even rough estimates show they don't collide nearly often enough to have produced all the gold found in the solar system, Kobayashi and her co-authors found.

"There's two stages to this question," she said. "Number one is: neutron star mergers are not enough. Number two: Even with the second source, we still can't explain the observed amount of gold."

Past studies were right that neutron star collisions release a shower of gold, she said. But those studies didn't account for the rarity of those collisions. It's hard to precisely estimate how often tiny neutron stars — themselves the ultra-dense remnants of ancient supernovas — slam together. But it's certainly not very common: Scientists have seen it happen only once. Even rough estimates show they don't collide nearly often enough to have produced all the gold found in the solar system, Kobayashi and her co-authors found.

Related: 15 amazing images of stars

"This paper is not the first to suggest that neutron star collisions are insufficient to explain the abundance of gold," said Ian Roederer, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan, who hunts traces of rare elements in distant stars.

But Kobayashi and her colleagues' new paper, published Sept. 15 in The Astrophysical Journal, has one big advantage: It's extremely thorough, Roederer said. The researchers poured over a mountain of data and plugged it into robust models of how the galaxy evolves and produces new chemicals.

"The paper contains references to 341 other publications, which is about three times as many references as typical papers in The Astrophysical Journal these days," Roederer told Live Science.

Pulling all that data together in a useful way, he said, amounts to a "Herculean effort."

Using this approach, the authors were able to explain the formation of atoms as light as carbon-12 (six protons and six neutrons) and as heavy as uranium-238 (92 protons and 146 neutrons). That's an impressive range, Roederer said, covering elements that are usually ignored in these types of studies.

Mostly, the math worked out.

Neutron star collisions, for example, produced strontium in their model. That matches observations of strontium in space after the one neutron star collision scientists have directly observed.

Magneto-rotational supernovas did explain the presence of europium in their model, another atom that has proved tricky to explain in the past.

But gold remains an enigma.

Something out there that scientists don't know about must be making gold, Kobayashi said. Or it's possible neutron star collisions make way more gold than existing models suggest. In either case, astrophysicists still have a lot of work to do before they can explain where all that fancy bling came from.

Originally published on Live Science.