Swarms of mutant bacteria look just like Van Gogh's 'Starry Night'

The artistic swirls were discovered by accident.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A group of swarming bacteria just created strikingly artistic (and swirly) "paintings" that are reminiscent of the masterpieces by iconic Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh.

Microbiologists noticed the similarities while studying the social cooperation of predatory bacteria called Myxococcus xanthus. Individuals in this species are known to form cooperative swarms, in which they share resources to help overwhelm their prey. The researchers were specifically studying a pair of proteins, TraA and TraB, that allow these microbes to recognize and bond with each other. To do this, the team created mutated strains of M. xanthus that overexpressed the genes behind these proteins, to see how they would change, the scientists reported in a study published Dec. 7 in the journal mSystems.

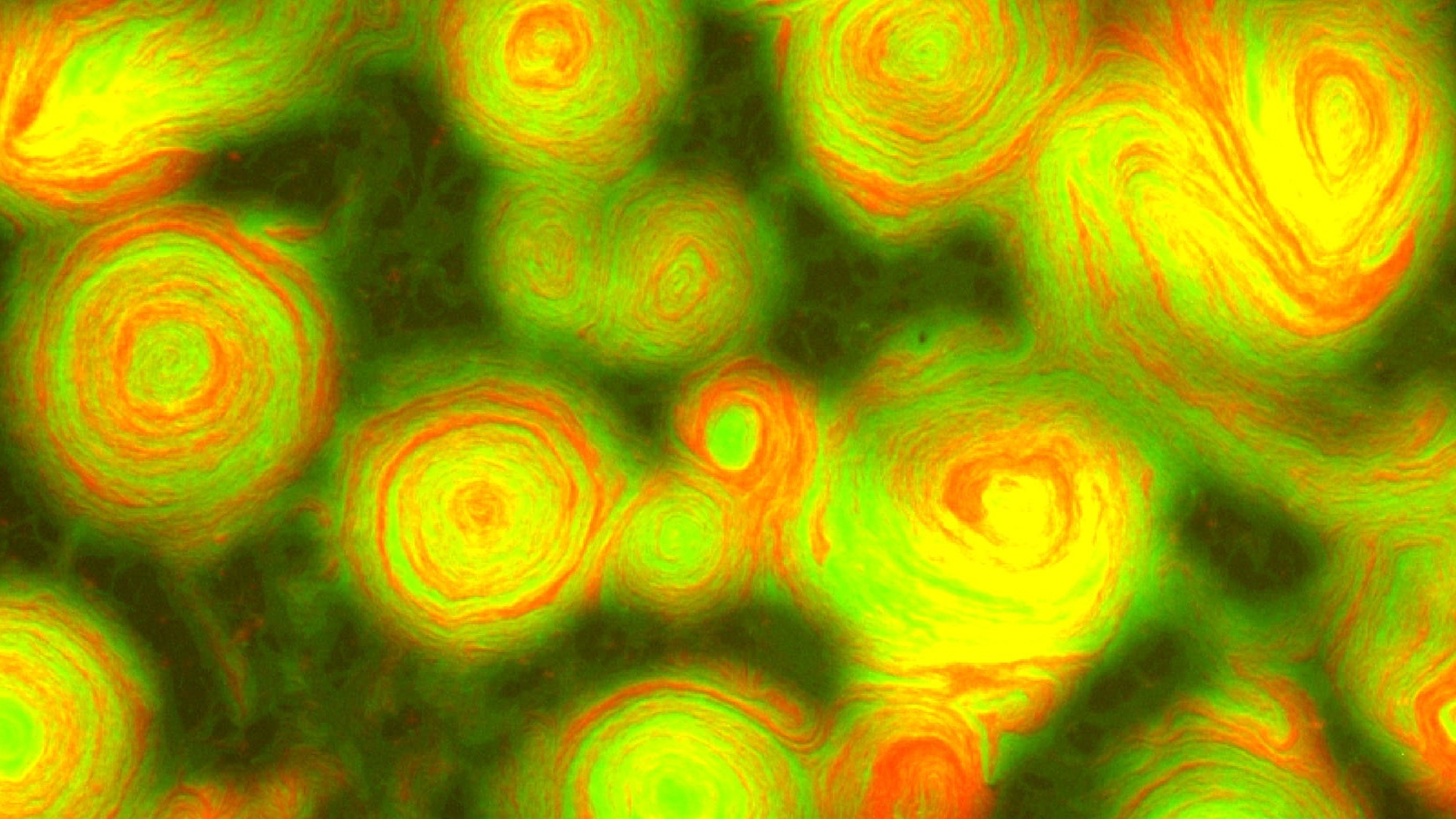

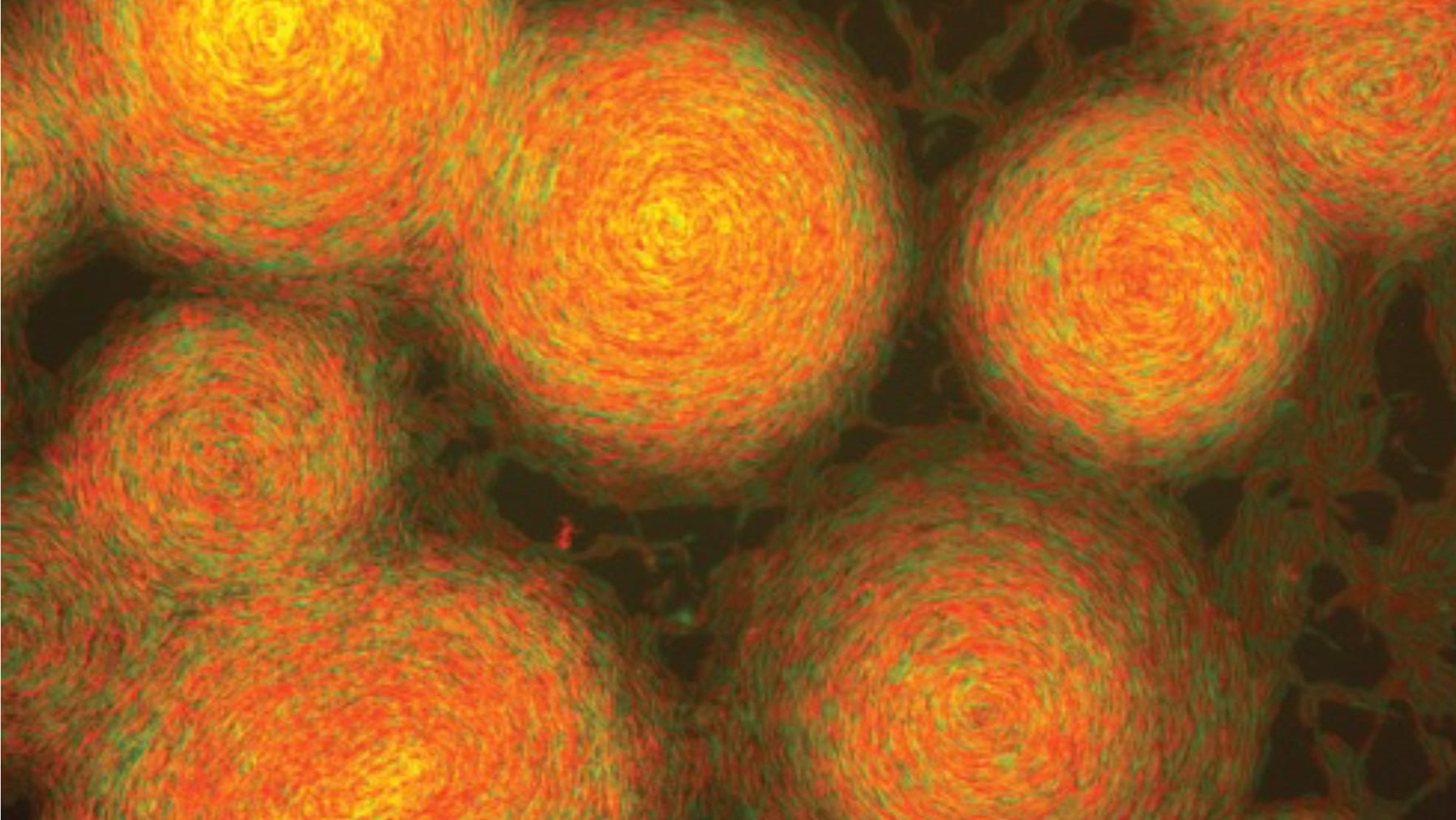

As the mutated strains formed swarms with other mutated strains and with nonmutated strains, the clumps of conjoined cells formed swirling patterns. The researchers then digitally added different colors to distinguish each strain. Once the color was added, the team realized the striking resemblance between the bacteria-made art and Van Gogh's, especially with the blue-and-yellow image that has a striking resemblance to "The Starry Night," one of the most famous pieces by the 19th-century painter.

Related: Gallery: 5 times science inspired art

The discovery highlights how studying social bacteria may reveal "behaviors that also exhibit artistic beauty," study co-author Daniel Wall, a molecular biologist at the University of Wyoming, said in a statement.

M. xanthus individuals form cooperative swarms by pooling their enzymes (proteins) and metabolites (chemicals), which help turn food into energy by speeding up metabolic reactions. This enables the bacteria to overwhelm their prey, which are typically other microbes. (They sometimes also gobble up other, unrelated strains of M. xanthus.) Normally, these swarms are head-to-tail chains of individual cells in a long line like a "commuter train," study co-author Oleg Igoshin, a computational biologist at Rice University in Texas, said in the statement. However, the mutations introduced in the lab caused the usual head-to-tail swarms to turn into rotating swirls of cells, each swirl as large as a millimeter (0.04 inch) or more.

"The cells are in dense groups and are in contact with others all the time," much more than in their usual swarms, Igoshin said in the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The overexpression of TraA and TraB also created stronger bonds that meant the bacteria swarms stuck together longer and seemed to be unable to revert to individual cells. In mutated strains, "your neighbor will remain your neighbor for longer," Igoshin said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus