10 incredible archaeological finds from 2022

The top 10 archaeological finds of 2022 include ancient bronze Etruscan statues from Italy, a Roman-era mosaic in Syria and a prehistoric chalk sculpture in England.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

There were many important archaeological discoveries in 2022. Researchers found evidence of prehistoric animations, one of the earliest known Buddhist temples and ancient Egyptian mummy portraits showing vivid images of the deceased — discoveries that captivated people around the globe. In this countdown Live Science takes a look at 10 of the most important archaeological stories from 2022.

1. Mummy portraits

Archaeologists with Egypt's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities discovered two complete mummy portraits along with semi-complete and incomplete portraits in a cemetery at the ancient city of Philadelphia, about 75 miles (120 kilometers) southwest of Cairo. These realistic portraits date back around 2,000 years.

While mummy portraits can be seen today in museums around the world, many were dug up by looters; the newfound paintings are the first mummy portraits found in a scientific excavation since the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie uncovered portraits in the 1880s. Scholars hope the new discoveries will help them learn more about mummy portraits, as the new finds were unearthed during an archaeological excavation and so were examined with modern scientific methods.

2. Underground city

A hidden underground city may have housed up to 70,000 people beneath the ancient city of Midyat in Turkey, archaeologists discovered. While only about 5% of the underground city has been excavated so far, finds include water wells, grain storage silos, the remains of houses, a Christian church and what seems to be a synagogue with a Star of David symbol on the wall. Coins and oil lamps found in the underground city suggest that it was in use during the second and third centuries A.D. During this time, the Roman Empire controlled the area and persecuted Christians, and it's possible that some people fled to this underground city to escape persecution.

3. Early Buddhist temple

Archaeologists working in Swat Valley, Pakistan found a Buddhist temple that dates to the mid-second century B.C., making it one of the oldest Buddhist temples in the world. Buddhism was founded by Siddhārtha Gautama, who lived from circa 563 B.C. to 483 B.C., meaning this temple dates to a few centuries after his death. Found in the town of Barikot, the uncovered remains of the temple so far include a ceremonial platform topped by a cylindrical structure that housed a stupa, a conical or dome-shaped Buddhist monument.

4. Destruction in Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine launched in February 2022 has resulted in the damage, destruction or theft of numerous artifacts and heritage sites. To name just a few examples, the world's largest plane, originally designed to carry a Soviet space shuttle, was destroyed in the opening days of the invasion. Occupation forces also took numerous artifacts from Melitopol Museum of Local History in Ukraine, including 2,300-year-old Scythian gold artifacts as well as 300-year-old silver coins and antique weapons.

Not even the dead have been spared. Before retreating from the Ukrainian city of Kherson in November, Russian occupation forces took the body of Grigory Potemkin (lived 1739 to 1791) from his grave in the city. Potemkin, a nobleman, was a favorite of Russian Empress Catherine the Great and served as both a governor and general. Media reports suggest that Russian president Vladimir Putin admires the figure and wanted his forces to remove the body and bring it to Russia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

5. Prehistoric cartoons

A research team studying a cave in southern France found that prehistoric animal carvings were positioned in such a way that light and shadows would interact with them to make it look like the animals were moving. "When you get this dynamic light across the surface, suddenly all these animals start to move; they start to flicker in and out of focus," Andy Needham, an archaeologist at the University of York in the United Kingdom, told Live Science. The site may date back around 15,000 years, and the carved animal animations long predate the earliest moving pictures, which didn't debut until the 19th century.

6. 9,000-year-old shrine discovery

A 9,000-year-old shrine discovered in Jordan's eastern desert contains a number of remarkable artifacts: at least two large stones with carvings of human facial features, an altar and hearth, animal figurines, stone tools and even marine fossils. Several full-size kites — a type of trap for capturing groups of animals — were found near the shrine, and it's possible that rituals at the shrine were performed in hopes of bringing about good hunting. While the area is now a desert, it's possible that it was wetter at the time the shrine was built.

7. Thousands of pits near Stonehenge

Researchers carrying out an electromagnetic induction survey discovered thousands of pits near Stonehenge. Results indicate that there may be 415 large pits that measured more than 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) in diameter and about 3,000 smaller pits. The oldest excavated pit was around 10,000 years old and contained the remains of stone tools that may have been used for hunting. At that time, many animals roamed Salisbury Plain, including aurochs (Bos primigenius), a now-extinct cattle species.

Only a small number of the pits have been excavated so far. Some may have been used for hunting, like the 10,000-year-old pit, while others may have had ceremonial purposes.

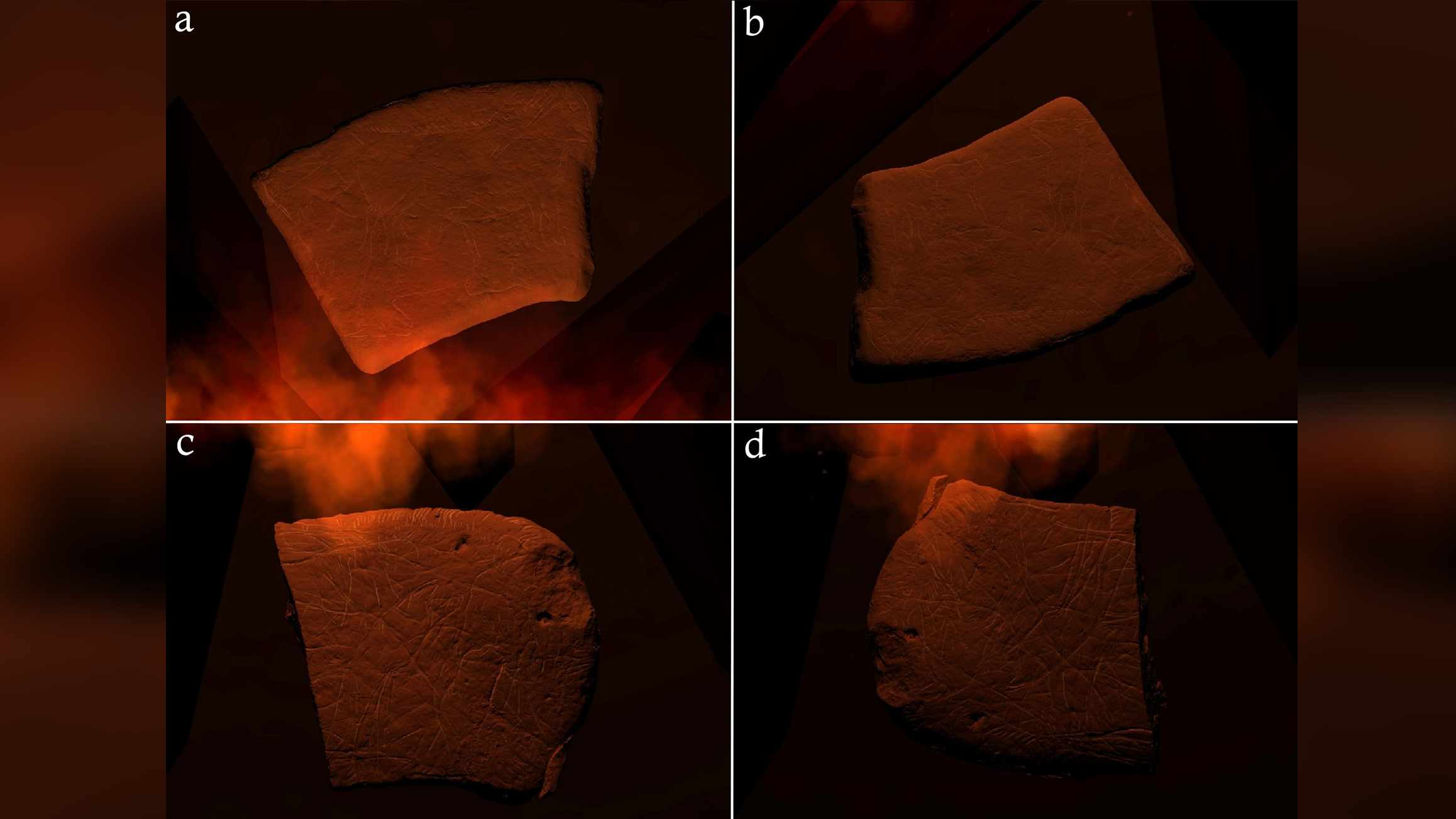

8. Ancient sanctuary

In the commune of San Casciano dei Bagni in Tuscany, Italy, archaeologists found what appears to be the remains of an ancient sanctuary. It may have been used by both the Etruscans and Romans. The Etruscans were a people who flourished in Italy during the first millennium B.C. but their cities and territory were gradually taken over by the Romans and their culture was absorbed by them. A team found more than two dozen well-preserved bronze statues dating to 2,000 years ago. Additionally, archaeologists found bronze carvings of individual body parts and organs, and 5,000 coins made of gold, silver or bronze.

At least some of the statues depict gods, including Apollo, a deity revered by both Greeks and Romans who was associated with the sun; and Hygeia, a goddess associated with healing. Some of the statues had Latin or Etruscan inscriptions carved on them.

9. Chalk sculpture

A 5,000-year-old chalk sculpture, which the British Museum called "the most important piece of prehistoric art to be found in Britain in the last 100 years," was found near the village of Burton Agnes in East Yorkshire. It was discovered alongside a chalk ball and bone pin inside the grave of three children.

The burial dates back to a time when Stonehenge was being built. The new finds are evidence that people across Britain were engaging in similar artistic practices at that time. For instance, the sculpture is similar to three other sculptures found in 1889 near the village of Folkton, about 15 miles (24 km) away from Burton Agnes. The bone pin found with the sculpture is similar to pins found interred with people inside Stonehenge, and the chalk ball is similar to another artifact found at Bulford, near Stonehenge.

10. Roman mosaic

In Syria, archaeologists uncovered a massive, colorful mosaic dating back about 1,600 years. It depicts scenes from the Trojan War, a legendary conflict between the Greeks and Trojans. It also shows scenes depicting the gods Hercules and Neptune. The mosaic is about 65.5 feet long by 20 feet wide (20 by 6 m) and was found in Rastan, a town near Homs, by archaeologists from the General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums, a Syrian government agency. The mosaic was found inside an ancient building whose purpose is unknown, although one idea is that it was a public bathhouse. Syria has been ravaged by a civil war since 2011 that has left many of its archaeological sites looted, damaged or destroyed.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus