The early universe was crammed with stars 10,000 times the size of our sun, new study suggests

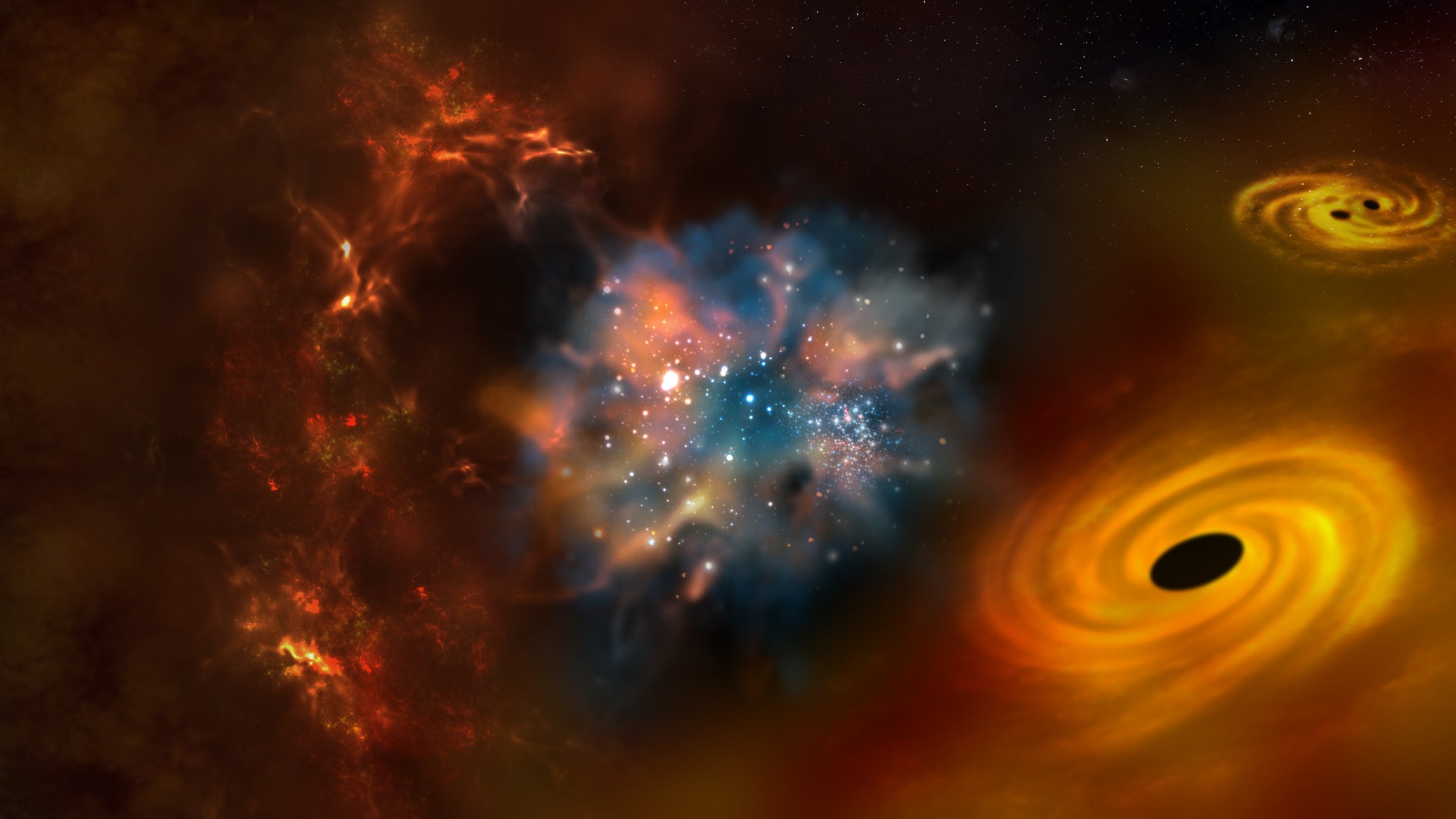

When the universe's first stars emerged from the cosmic dark ages, they ballooned to 10,000 times the mass of Earth's sun, new research suggests.

The first stars in the cosmos may have topped out at over 10,000 times the mass of the sun, roughly 1,000 times bigger than the biggest stars alive today, a new study has found.

Nowadays, the biggest stars are 100 solar masses. But the early universe was a far more exotic place, filled with mega-giant stars that lived fast and died very, very young, the researchers found.

And once these doomed giants died out, conditions were never right for them to form again.

The cosmic Dark Ages

More than 13 billion years ago, not long after the Big Bang, the universe had no stars. There was nothing more than a warm soup of neutral gas, almost entirely made up of hydrogen and helium. Over hundreds of millions of years, however, that neutral gas began to pile up into increasingly dense balls of matter. This period is known as the cosmic Dark Ages.

In the modern day universe, dense balls of matter quickly collapse to form stars. But that’s because the modern universe has something that the early universe lacked: a lot of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. These elements are very efficient at radiating energy away. This allows the dense clumps to shrink very rapidly, collapsing to high enough densities to trigger nuclear fusion – the process that powers stars by combining lighter elements into heavier ones.

But the only way to get heavier elements in the first place is through that same nuclear fusion process. Multiple generations of stars forming, fusing, and dying enriched the cosmos to its present state.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Without the ability to rapidly release heat, the first generation of stars had to form under much different, and much more difficult, conditions.

Cold fronts

To understand the puzzle of these first stars, a team of astrophysicists turned to sophisticated computer simulations of the dark ages to understand what was going on back then. They reported their findings in January in a paper published to the preprint database arXiv and submitted for peer review to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The new work features all the usual cosmological ingredients: dark matter to help grow galaxies, the evolution and clumping of neutral gas, and radiation that can cool and sometimes reheat the gas. But their work includes something that others have lacked: cold fronts – fast-moving streams of chilled matter – that slam into already formed structures.

The researchers found that a complex web of interactions preceded the first star formation. Neutral gas began to collect and clump together. Hydrogen and helium released a little bit of heat, which allowed clumps of the neutral gas to slowly reach higher densities.

But high-density clumps became very warm, producing radiation that broke apart the neutral gas and prevented it from fragmenting into many smaller clumps. That means stars made from these clumps can become incredibly large.

Supermassive stars

These back-and-forth interactions between radiation and neutral gas led to massive pools of neutral gas– the beginnings of the first galaxies. The gas deep within these proto-galaxies formed rapidly spinning accretion disks – fast-flowing rings of matter that form around massive objects, including black holes in the modern universe.

Meanwhile, on the outer edges of the proto-galaxies, cold fronts of gas rained down. The coldest, most massive fronts penetrated the proto-galaxies all the way to the accretion disk.

These cold fronts slammed into the disks, rapidly increasing both their mass and density to a critical threshold, thereby allowing the first stars to appear.

Those first stars weren’t just any normal fusion factories. They were gigantic clumps of neutral gas igniting their fusion cores all at once, skipping the stage where they fragment into small pieces. The resulting stellar mass was huge.

Those first stars would have been incredibly bright and would have lived extremely short lives, less than a million years. (Stars in the modern universe can live billions of years). After that, they would have died in furious bursts of supernova explosions.

Those explosions would have carried the products of the internal fusion reactions – elements heavier than hydrogen and helium – that then seeded the next round of star formation. But now contaminated by heavier elements, the process couldn’t repeat itself, and those monsters would never again appear on the cosmic scene.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.