Powerful solar ‘burp’ flares on the surface of the sun

Our solar neighbor has been zinging out bursts like this all week.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

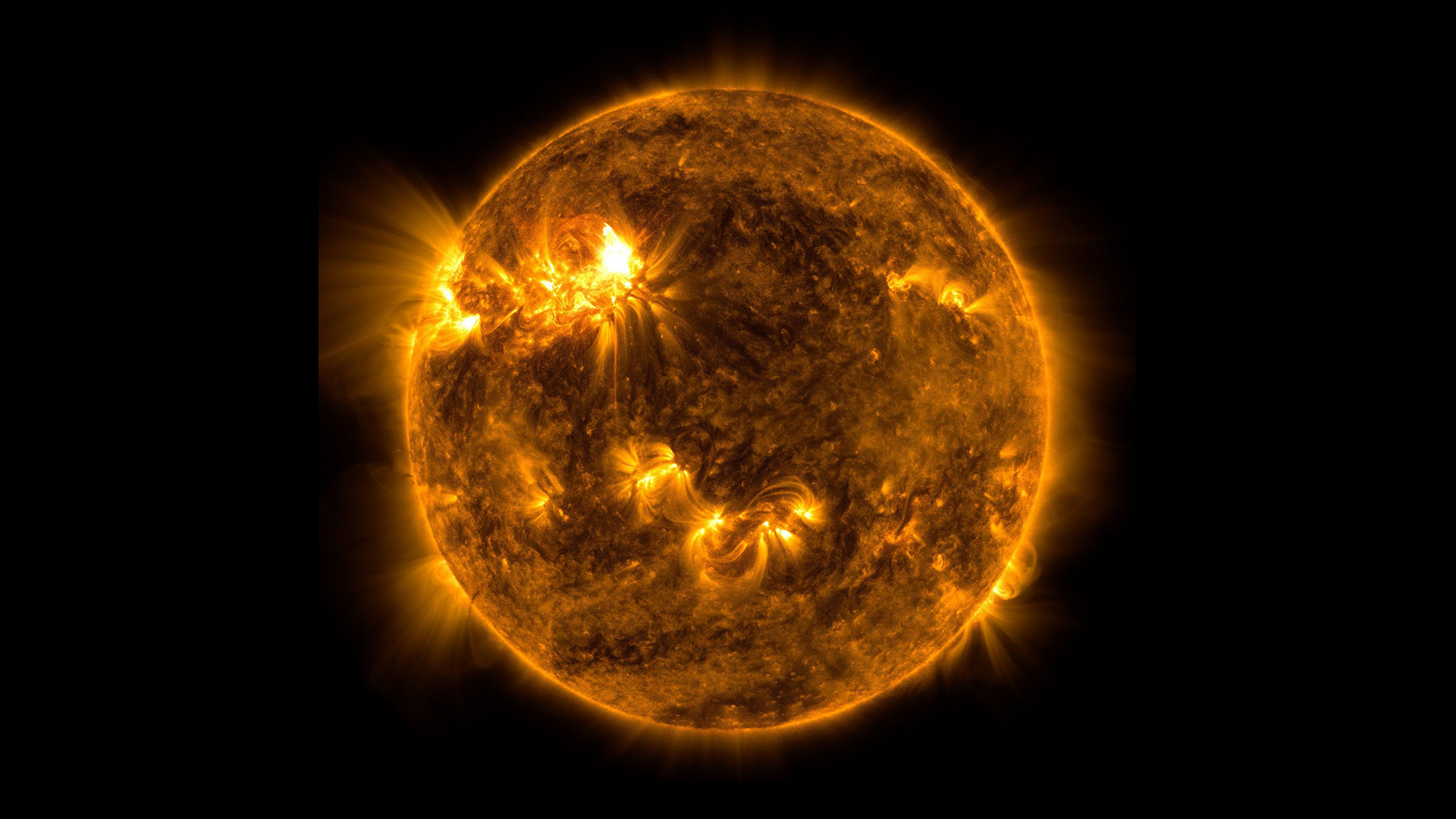

The sun is a beehive of flaring activity in a stunning new photo from a NASA spacecraft.

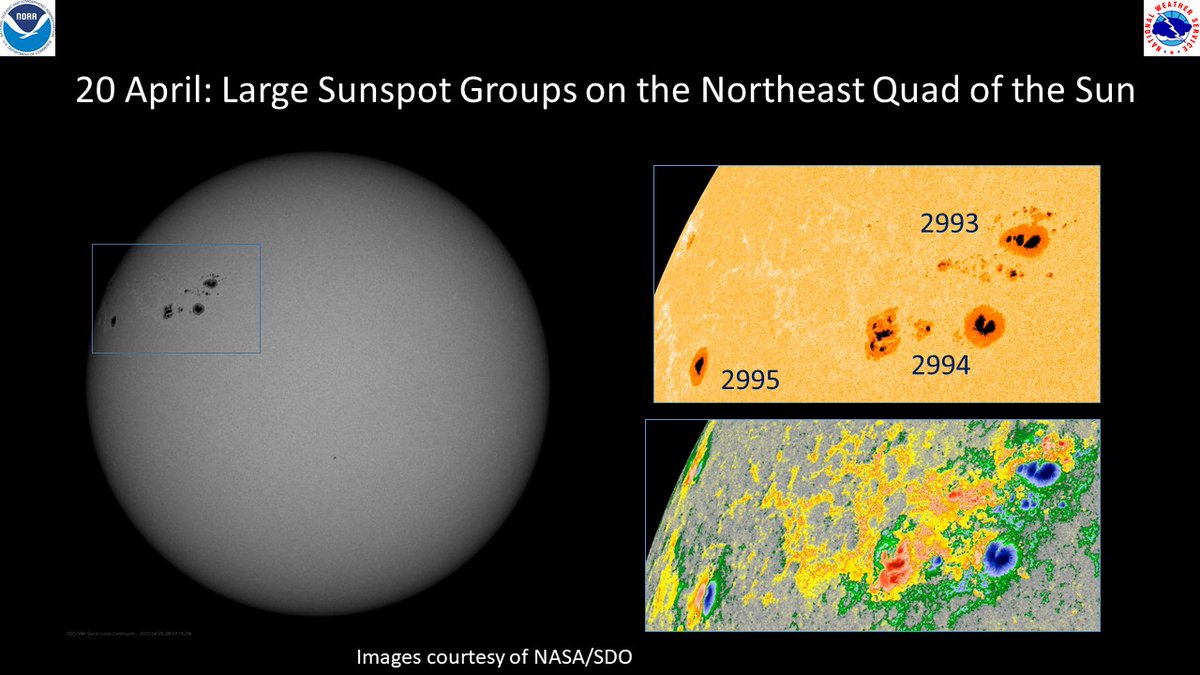

NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory caught the sun in action as it flung a moderate-sized flare into space on Wednesday (April 20). The flare was just one of dozens of plasma projectiles that the sun generated in just a few hours.

This particular flare peaked Wednesday at 9:59 p.m. EDT (1359 GMT Thursday, April 21), NASA officials said in a release. The agency did not provide a specific forecast associated with the event, but it did state that "solar flares are powerful bursts of energy. Flares and solar eruptions can impact radio communications, electric power grids, navigation signals, and pose risks to spacecraft and astronauts."

While NASA did not share a forecast associated with the event, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration advised that there is a moderate probability of auroras in the next 24 hours.

Related: Earth braces for solar storm, potential aurora displays

This latest missive came after the sun sent out dozens of flares within a few hours, including the most powerful class of solar flare, X-class. The biggest flares came from sunspot AR2992, which is on the edge of the sun. Since Earth wasn't quite within firing range, it appears there is no incoming set of auroras associated with that sunspot's outburst.

Auroras can occur after a solar flare when the charged particles from coronal mass ejections reach Earth and flow across our planet's magnetic field lines. As the particles hit bits of Earth's atmosphere high above us, the atmospheric molecules get "excited" and begin to glow. Forecasts Wednesday (April 20) suggested a CME was brewing, but was likely not to strike Earth given the sunspot was facing in a direction mostly away from our planet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The flaring sun and huge groups of sunspots on its surface show that the sun is starting to emerge from the quieter beginning of the solar cycle, which began in 2019. The 11-year cycle should peak in 2025.

Most CMEs are harmless, aside from the sky shows and brief radio blackouts. But NASA and other agencies do keep a sharp eye on the sun in case of larger events. The most powerful storms, albeit rare, can create issues with infrastructure such as satellites or power lines.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus