India's lunar lander finds 1st evidence of a moonquake in decades

The possible moonquake was detected by India's Chandrayaan-3 mission on its third day on the lunar surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

India's moon rover may have just detected the first evidence of a "moonquake" since the 1970s.

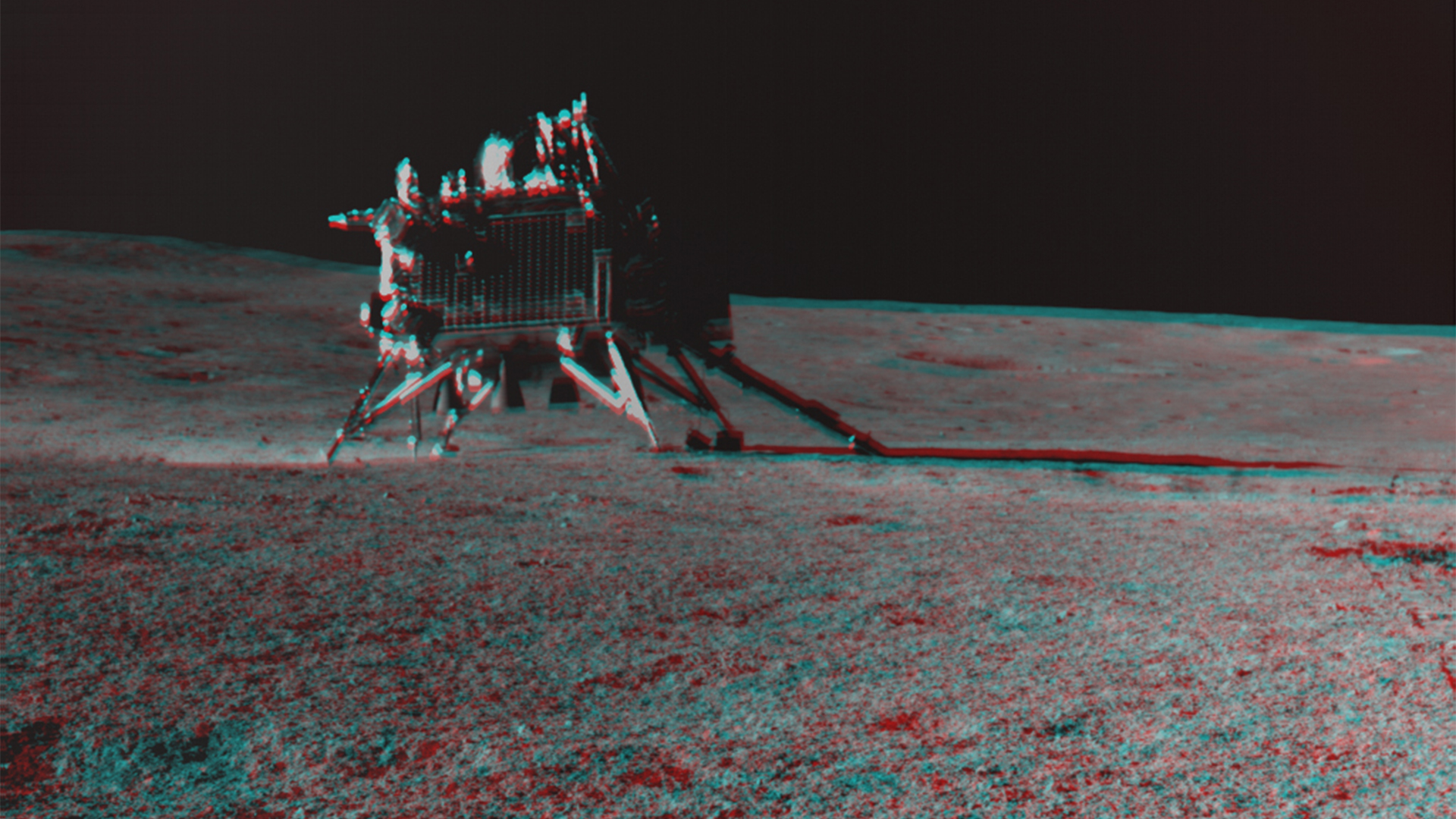

The Instrument for Lunar Seismic Activity (ILSA) attached to the Vikram lander detected the seismic activity on the surface of the moon Aug. 26. Vikram landed on the moon's south pole Aug. 23 as part of the Chandrayaan-3 mission — India's first mission to the lunar surface.

If it's confirmed, the moonquake — which the mission detected alongside other activity including the movements of India's Pragyan rover — could give scientists a rare insight into the mysterious churning innards of Earth's lunar companion.

Related: Why can we sometimes see the moon in the daytime?

The lander "has recorded an event, appearing to be a natural one, on August 26, 2023," The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) wrote on X, formerly Twitter. "The source of this event is under investigation."

The Apollo lunar missions between 1969 and 1977 first detected seismic activity on the moon, which proved that the moon had a complex geological structure hidden deep within, rather than being uniformly rocky like the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos.

In recent years, advanced analysis tools and computer models have enabled scientists to sift through the data gathered by Apollo and other missions and build a clearer picture of the moon's mysterious interior. A 2011 NASA study revealed that the moon's core, much like Earth's, was likely made up of fluid iron surrounding a dense, solid iron ball.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In May 2023, researchers used gravitational field data to confirm this iron core hypothesis, while also suggesting that blobs of the moon's molten mantle could be separated from the rest, floating to the surface as clumps of iron and generating quakes as they went.

But these findings are just the beginning of the moon's secrets. Magnetic fields are produced inside planetary bodies by the churning movement of material in planets' electrically conductive molten cores.

Today the interior of the non-magnetic moon is quite different from Earth's magnetized innards — it's dense and mostly frozen, containing only a small outer core region that is fluid and molten. Scientists believe that the moon's insides cooled fairly quickly and evenly after it formed around 4.5 billion years ago, meaning it doesn't have a strong magnetic field — and many scientists believe it never did.

How then, could some of the 3 billion-year-old rocks retrieved during NASA's Apollo missions look like they were made inside a geomagnetic field powerful enough to rival Earth's?

It is questions like these that the Chandrayaan-3 could help to answer. As the mission's lander and rover are both solar-powered, they are currently in sleep mode until the moon exits its roughly 14-day night. When the sun hits the face of the lunar south pole again on Sept. 22, both tools stand poised to search for the answers.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus