China aims to be 1st to bring samples back from Mars

China's planned mission to bring rock samples to Earth from Mars would beat both NASA and the European Space Agency to the punch.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

China's space agency could be the first to bring samples from Mars to Earth, in a plan that would return Martian rocks and sediment in 2031.

In a paper published in the November issue of the journal National Science Review, researchers from the Deep Space Exploration Laboratory and collaborating institutions within China laid out a plan for Tianwen-3, a two-spacecraft Mars lander mission planned by the China National Space Administration. In a September update at a space exploration conference, Jizhong Liu, the chief designer of Tianwen-3, said the mission is on track to launch in 2028.

According to Space News, Tianwen-3 will include a lander, an ascent vehicle, an orbiter and a return module; it also may use a helicopter and a six-legged robot for gathering samples at a distance from the lander.

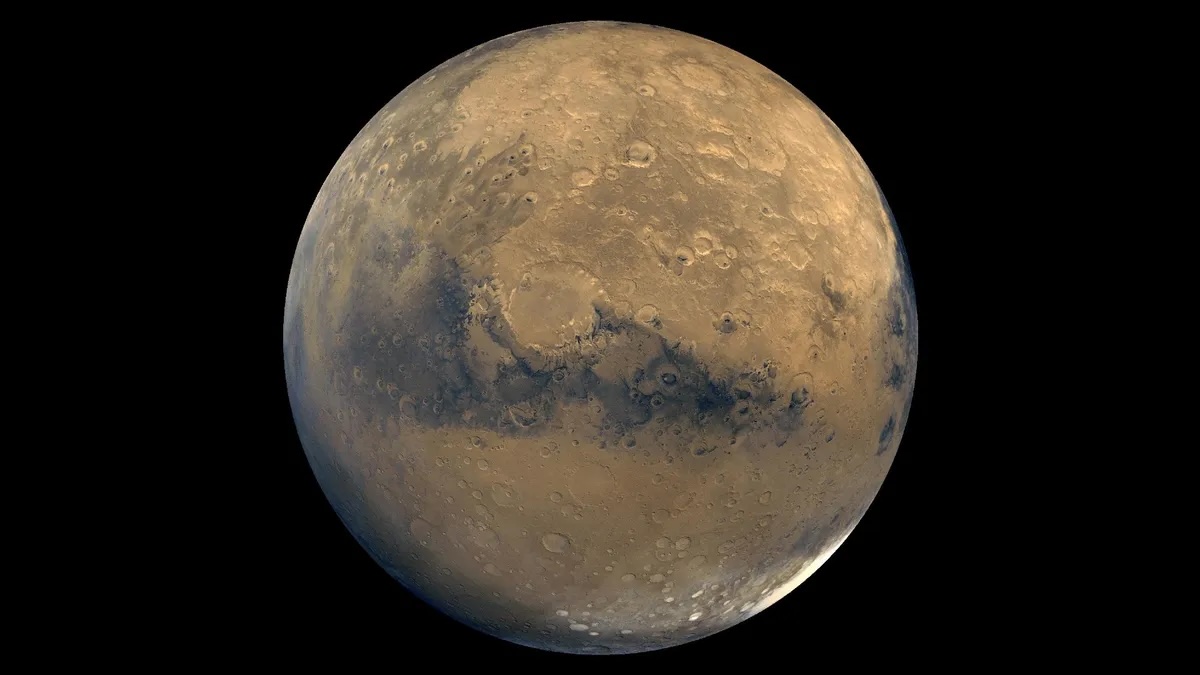

In the National Science Review paper, Zengqian Hou of the Deep Space Exploration Laboratory and Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences reported that there are 86 potential sites being considered for the Tianwen-3 landing spot. Most are clustered in Chryse Planitia, a smooth plain in Mars' northern equatorial region, and Utopia Planitia, the largest impact basin on Mars, where China landed a rover in 2021.

Related: Why can't we see the far side of the moon?

These sites are promising for the key aim of the Tianwen-3 mission, which is to look for signs of past life on Mars, Hou and his colleagues wrote. The sites were chosen because they offer relatively forgiving landing topography and because rocks and sediment there might still preserve traces of ancient Martian life.

A 2028 launch would bring Tianwen-3 back to Earth in 2031. (A one-way trip between Earth and Mars takes between seven and 11 months, depending on the alignment of the planets on a given date.) Samples would be analyzed in multiple ways, Hou and his team wrote. These methods would include mass spectrometry, to determine their elemental makeup, and isotopic analysis, to look at the ratio of different versions of elements that might indicate the past presence of living organisms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If the Tianwen-3 mission remains on track, it will beat NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) in bringing Mars rocks back to Earth by nearly a decade. NASA announced in April that the planned Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission, a joint effort between NASA and ESA, would be delayed until the 2030s. Under the current plan, the MSR lander would launch in 2035, and the sample-return mission wouldn't occur until 2040.

China's Chang'e-6 mission recently brought back the first-ever samples from the far side of the moon. An early analysis revealed the first evidence of volcanic activity on the lunar far side, suggesting volcanoes were erupting there as recently as 2.8 billion years ago.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus