Father-daughter team decodes 'alien signal' from Mars that stumped the world for a year

A father and daughter team based in the U.S. have decoded a mock "alien signal" beamed from ESA's ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter a year ago — but the meaning of the extraterrestrial message remains a mystery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A father-daughter team has decoded a mock "alien" message after a year of trying. Now, citizen scientists are trying to figure out what the decoded missive truly means for Earth.

According to the European Space Agency (ESA), Ken and Keli Chaffin from the U.S. were the first to crack the code, which was sent from ESA's ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter as part of a citizen science project in May 2023. Three radio observatories on Earth heard the message, and the data were made available to the public. The first step was to extract the signal from the raw data, and the second was to decode it.

The message is part of "A Sign in Space," a science/art project that explores how humanity might react after receiving a real alien message. It took only 10 days for an online community to extract the message from the raw data, but decoding it was more difficult: That wasn't achieved until June 7, 2024, when the Chaffins messaged Daniela de Paulis, the founder and artistic director of the project, with the solution. ESA publicly announced their success on Oct. 22.

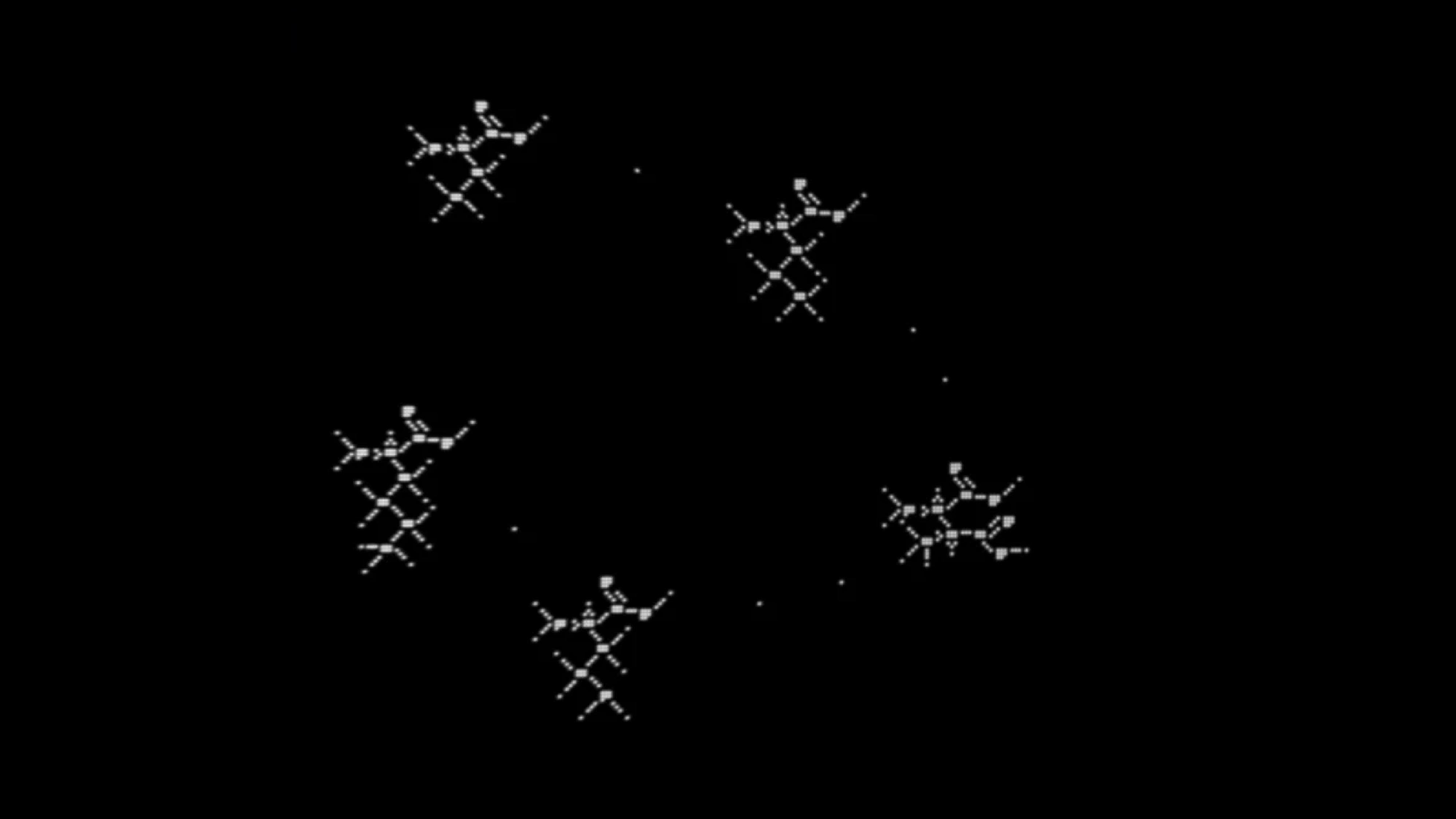

The message turned out to be an image depicting the structure of five amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. It was the brainchild of a group of "simulated extraterrestrials," according to A Sign in Space, which included de Paulis, as well as a computer scientist, a poet, a radio engineer, a physicist and space lawyer, and several astronomers and astrobiologists.

Related: Infamous 'Wow! signal' that hinted at aliens may actually be an exceptionally rare cosmic event

The project had additional support from the SETI Institute — a nonprofit dedicated to the search for extraterrestrial life — and the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia. Decoding the message required many hours of computer simulations. The Chaffins managed to crack the code when they figured out that the message included some biological features, ESA reported.

But what would aliens be trying to convey by sending a picture of five amino acids? That mystery still needs to be solved. Now, citizen scientists are gathering on a Discord server to debate and puzzle over the message's meaning. Do aliens come in peace? That question might be the toughest to answer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus