13 billion-year-old 'streams of stars' discovered near Milky Way's center may be earliest building blocks of our galaxy

Two gargantuan structures discovered near our galaxy's ancient heart may be some of the earliest building blocks of the Milky Way. Researchers have named them Shiva and Shakti.

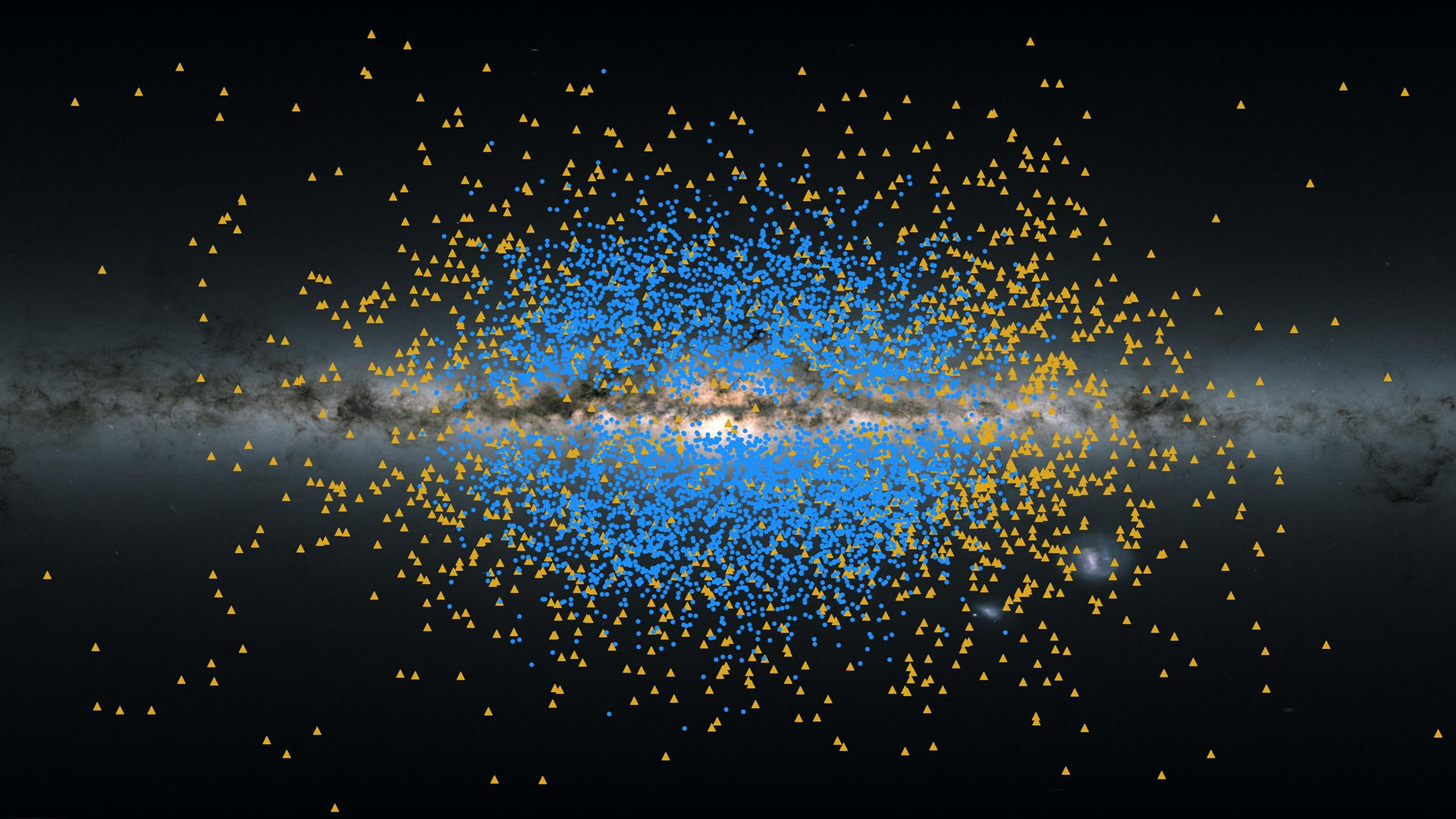

Astronomers peering into the heart of the Milky Way have discovered two gargantuan, never-before-seen structures. These vast "streams" of stars each contain the mass of 10 million suns and are up to 13 billion years old. They span wide swathes of the galaxy and may be some of the earliest building blocks of our Milky Way, scientists with the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) said.

The two structures — described in a new study published March 21 in The Astrophysical Journal — have been named Shiva and Shakti, after the divine Hindu couple whose union is said to have brought harmony to the universe. The newfound stellar streams appear to have merged with the early Milky Way between 12 billion and 13 billion years ago, fueling our galaxy's growth.

"What's truly amazing is that we can detect these ancient structures at all," lead study author Khyati Malhan, an astrophysicist at MPIA said in a statement. "The Milky Way has changed so significantly since these stars were born that we wouldn't expect to recognise them so clearly as a group."

The researchers spotted the cosmic structures using the European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope — a floating observatory that's been mapping the shape and structure of the Milky Way since 2014. By charting the speed, position and motion of more than 1.5 billion stars in our galaxy, Gaia's observations enable astronomers to draw connections between groups of stars that share similar origins, helping to piece together our galaxy's history.

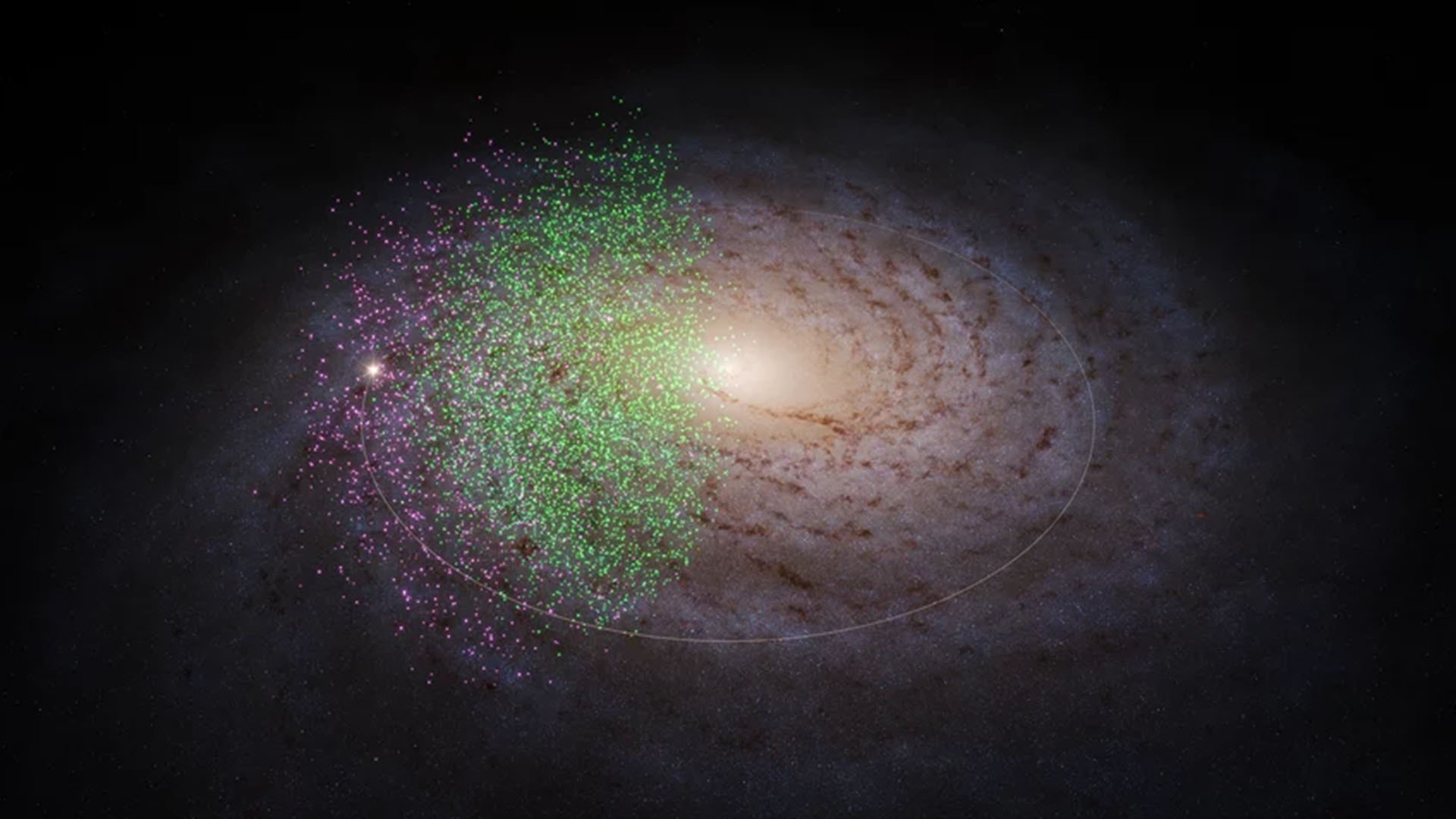

It's thought that the Milky Way has collided with neighboring galaxies at least a dozen times over the last 12 billion years, with each merger funneling fresh stars into our evolving galaxy. The Gaia telescope has helped reveal several of these collisions — including a previously unknown merger with the so-called Gaia sausage dwarf galaxy, which our insatiable Milky Way swallowed 10 billion years ago, giving our galaxy its bulging center.

The millions of stars that make up Shiva and Shakti also seem to have contributed to our galaxy's overall structure but are located a bit further from the galactic center than previously identified fragments like the Gaia sausage.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Until now, we had only recognised these very early fragments that came together to form the Milky Way's ancient heart," study co-author Hans-Walter Rix, director of the department of galaxies and cosmology at MPIA, said in the statement. "With Shakti and Shiva, we now see the first pieces that seem comparably old but located further out. These signify the first steps of our galaxy's growth towards its present size."

The team's analysis showed that Shakti's stars orbit further from the galactic center and in a more circular orbit than Shiva's — but both structures contain stars that are extremely metal poor, meaning they lack the heavier elements forged through stellar fusion later in the universe's history. This means Shiva and Shakti likely contain some of the oldest stars in the Milky Way, making the newfound streams some of the first building blocks upon which the galaxy evolved.

To better understand how Shiva and Shakti's union with the Milky Way contributed to the current state of our galaxy, the team will continue studying them through several ongoing sky surveys. Sadly, there is a strict deadline for this research: In about 4.5 billion years, the Milky Way's next big collision will unfold as the nearby Andromeda galaxy merges with ours. Whatever life exists on our planet then will have a completely different view of the night sky than we do today.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus