Scientists discover closest star-shredding black hole to Earth ever seen

Astronomers comparing maps of the universe uncovered the nearest example of a black hole devouring a star ever detected.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

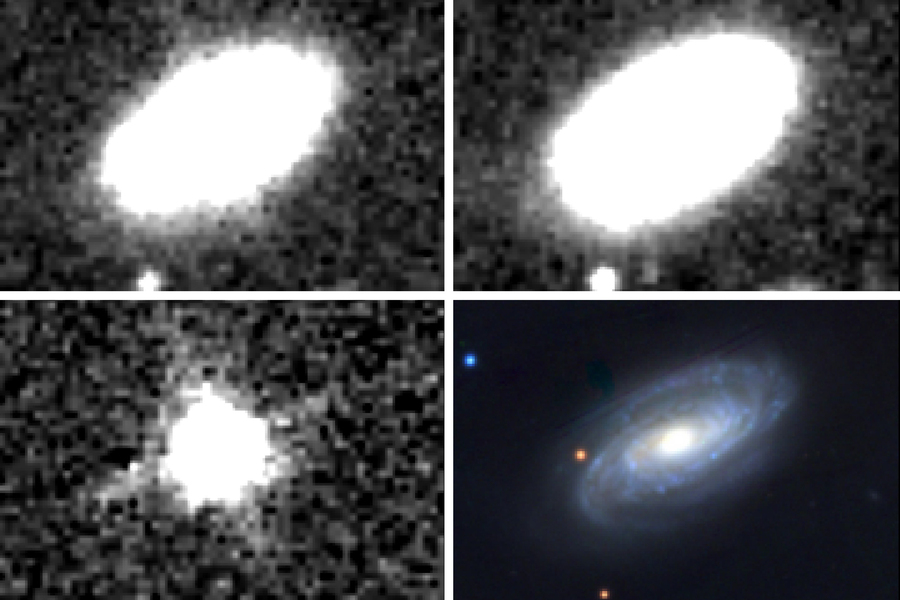

A long time ago, in a galaxy not so far away, a supermassive black hole ripped a star to shreds in the center of the galaxy NGC 7392. The flash of light from the black hole's dinner finally reached Earth in 2014 — and astronomers just discovered it in their data.

This newly detected outburst from the center of NGC 7392 is the closest-yet example of a tidal disruption event (TDE), where a star is pulled apart by the massive gravitational pull of a black hole. The findings were published April 28 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The hungry black hole was spotted roughly 137 million light-years from Earth — or about 35 million times as far as Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the sun. As distant as that sounds, astronomers have only observed around 100 of these events so far, and this one is four times closer than the previous title-holder of "closest TDE to Earth." Scientists discovered the TDE in infrared, a different wavelength than most conventional TDE detections, which usually come in X-rays, ultraviolet, and optical light.

Related: Meet 'Scary Barbie,' a black hole slaughtering a star in the brightest way possible

"Finding this nearby TDE means that, statistically, there must be a large population of these events that traditional methods were blind to," said lead author Christos Panagiotou, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in a statement. "So, we should try to find these in infrared if we want a complete picture of black holes and their host galaxies."

After first spotting the TDE in observations from the NEOWISE space telescope, Panagiotou and collaborators sifted through data from many other observatories and space telescopes to dig up more information on NGC 7392's supermassive black hole. They wanted to solve the mystery of why this TDE only appeared in infrared, instead of in more energetic wavelengths like others of its kind.

Previously discovered TDEs mostly appeared in so-called green galaxies, which don’t create quite as many stars as the more active blue galaxies but aren't totally burned-out on star-making like red galaxies. NGC 7392, however, is a blue galaxy — churning out many new stars and creating a lot of dust in the process. This dust could obscure the center of the galaxy, where the supermassive black hole lives, in optical and ultraviolet light. But infrared light enables astronomers to peer through that dust and see what's going on.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This finding suggests that astronomers should be searching for TDEs in infrared light, too.

"Using infrared surveys to catch the dust echo of obscured TDEs has already shown us that there is a population of TDEs in dusty, star-forming galaxies that we have been missing," Suvi Gezari, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute who was not involved in the study, said in the statement.

By looking for TDEs in infrared too, scientists could get one step closer to understanding how black holes chow down on stars.

Briley Lewis (she/her) is a freelance science writer and Ph.D. Candidate/NSF Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles studying Astronomy & Astrophysics. Follow her on Twitter @briles_34 or visit her website www.briley-lewis.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus