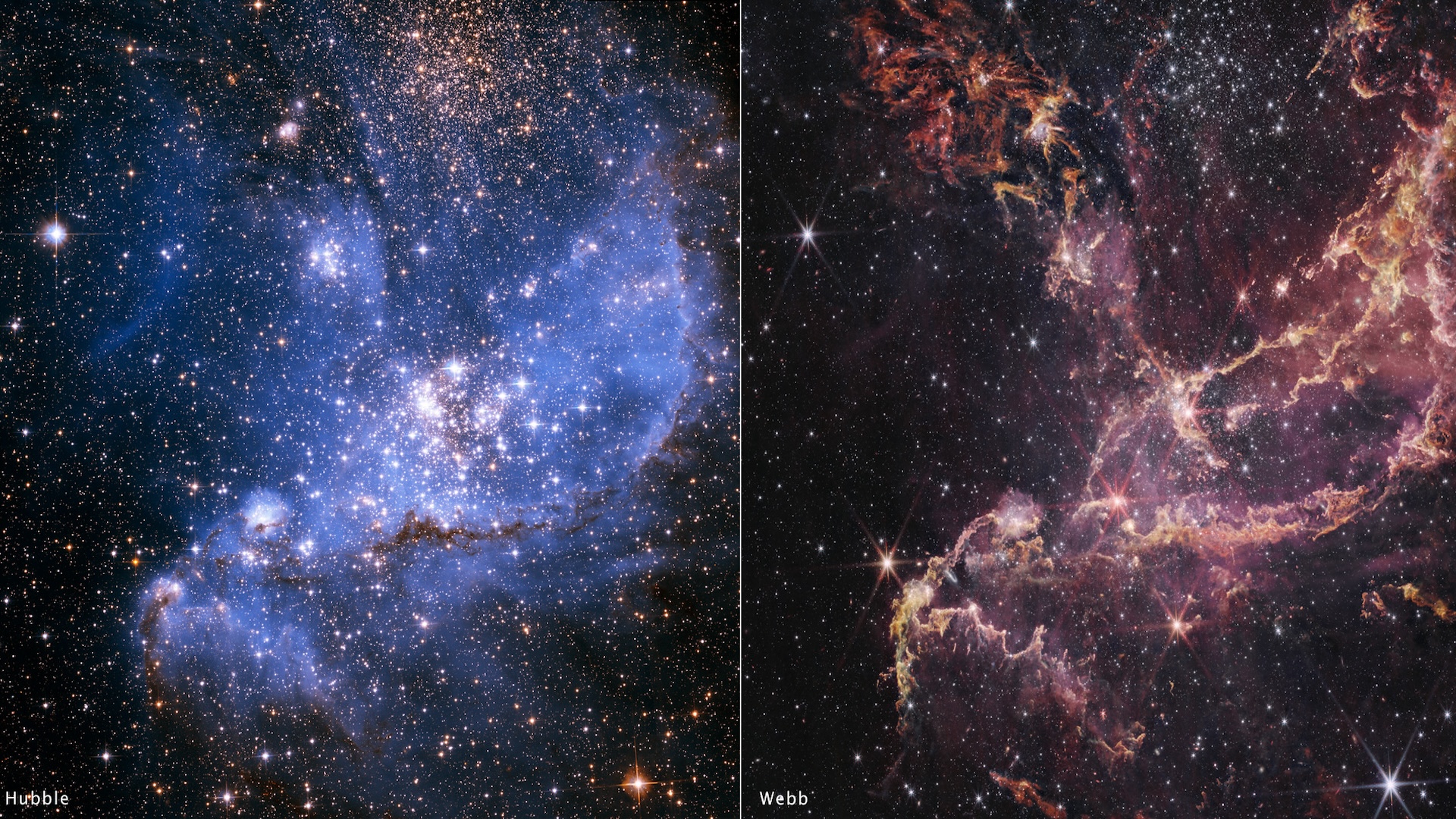

Space photo of the week: James Webb and Hubble telescopes unite to solve 'impossible' planet mystery

New James Webb Space Telescope observations of a star cluster called NGC 346 are shedding light on how, when and where planets formed in the early universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What it is: An open cluster of stars called NGC 346

Where it is: 210,000 light-years away, in the constellation Tucana

When it was shared: Dec. 16, 2024

Why it's so special: This James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) image has helped astronomers untangle a long-standing mystery about how planets form. The mystery arose more than 20 years ago, when the Hubble Space Telescope spotted the universe's oldest known planet, which formed earlier in the universe's history than scientists thought was possible.

Stars form in large clouds of gas and dust called molecular clouds. Any remaining gas and dust gather in disks around the stars. Planets, in turn, form from these disks. Scientists believed that early stars didn't have planets because there was a lack of heavier elements, such as carbon and iron, which are created by stars' nuclear fusion and supernova deaths. They thought that these heavier elements were essential for planet-forming disks to exist long enough for planets to form.

Related: Space photo of the week: The tilted spiral galaxy that took Hubble 23 years to capture

But in 2003, Hubble detected a massive planet orbiting an ancient star in the M4 globular cluster, which is about 5,600 light-years distant in the Milky Way. Globular clusters are extremely old and, therefore, lack heavier elements. The exoplanet is about 13 billion years old, which suggests that planets may have formed earlier in the universe's history than scientists thought was possible. But astronomers were unsure exactly how it formed so early in the universe's history.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To learn more about the early universe, astronomers use proxies that have similar conditions to ancient galaxies. One such proxy is the star cluster NGC 346, a star-forming region within the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), a dwarf galaxy that orbits the Milky Way. Like early galaxies, the SMC lacks heavier elements and is made up mainly of hydrogen and helium.

When astronomers pointed Hubble at NGC 346, they found signs that planet-forming disks existed around stars for 20 million to 30 million years — about 10 times longer than theories predicted such disks could survive. However, the signs were faint, so astronomers needed further proof.

In 2023, JWSTused the unprecedented sensitivity and resolution provided by its Near Infrared Spectrograph and Mid-Infrared Instrument to confirm the existence of long-lived planet-forming disks in NGC 346.

The findings, published Dec. 16, 2024, in The Astrophysical Journal, affirm the Hubble result and suggest that the lack of heavier elements may slow the star's ability to disperse its planet-forming disk — giving planets more time to form. Another theory is that the initial gas cloud from which the star forms might be larger, resulting in a more massive, longer-lived disk.

For more sublime space images, check out our Space Photo of the Week archives.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus