The largest telescope on Earth is coming to hunt radio-waves from the early universe

After 30 years of planning, construction of the SKA Telescope, set to be the world's largest telescope array, began in South Africa on December 5.

Construction has started on the largest telescope array on Earth.

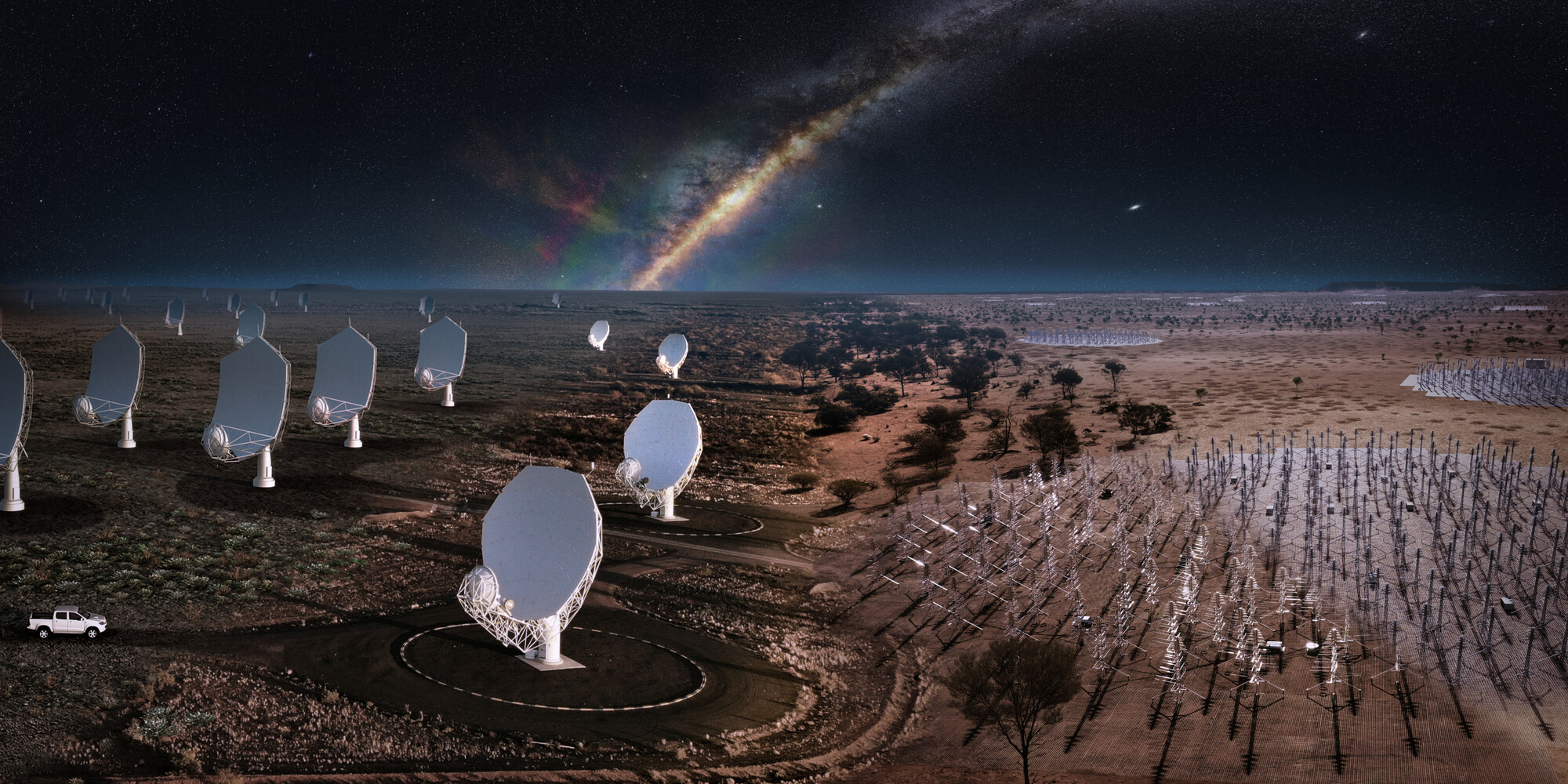

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which will contain hundreds of radio antennae spread across two continents, is now under construction in both South Africa's Karoo region and Western Australia's Murchison Shire.

Together, the two sites – named SKA-Mid and SKA-Low, for the types of radio frequencies they will primarily detect – will enable high-resolution imaging of the whole sky, according to the Square Kilometre Array Observatory (SKAO), the organization that oversees the telescope. The sensitivity of the telescope will allow scientists to pick up even faint signals left over from the earliest days of the universe.

"The SKA project has been many years in the making," SKAO council chair Catherine Cesarsky said in an address at the South Africa site Monday (Dec. 5). "Today, we gather here to mark another important chapter in this 30-year journey that we've been on together. A journey to deliver the world's largest scientific instrument."

The planning stages of the telescope have spanned three decades, with pre-planning and contracting picking up speed in the past 18 months. The goal is to complete the telescope arrays by 2030.

The Australia site will host 131,072 low-frequency antennae placed as far as 40.4 miles (65 kilometers) apart. Together, they'll act as a radio telescope with a lens spanning nearly 100 acres (400,000 square meters). Each antenna station is 6.6 feet (2 m) tall and contains 256 antennae in a configuration that looks a bit like a pine tree. By catching very-low-frequency signals from the whole sky, SKA-Low will be able to delve into some of the oldest echoes left over from the first billion years of the universe, according to SKAO.

The site is on the land of the Indigenous Wajarri Yamaji, who signed a land-use agreement to ensure that the telescope did not interfere with any cultural sites and that locals would receive economic and educational benefits from the site. As a part of the agreement, the Wajarri Yamaji bestowed the traditional name "Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara" on the site, which means "sharing the sky and stars."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The South Africa site will consist of 197 parabolic discs spread as far as 93.2 miles (150 km) from one another. They'll be linked to the existing MeerKAT radio telescope, and will be the equivalent of a single telescope with an 8.2-acre (33,000 square meters) lens. SKA-Mid will be five times more sensitive, four times higher-resolution and 60 times faster at scanning the sky than the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) telescope, the current state-of-the-art radio telescope, located in New Mexico.

Both Murchison Shire and Karoo were chosen for their remoteness and relative lack of human-made radio signals that might interfere with the detection of radio signals from deep space. Scientists around the world plan to use data from the telescope to study questions ranging from the fundamental nature of dark energy to the nature of mysterious fast radio bursts from distant galaxies.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus