Should you get a second booster shot for COVID-19?

Is a second booster recommended?

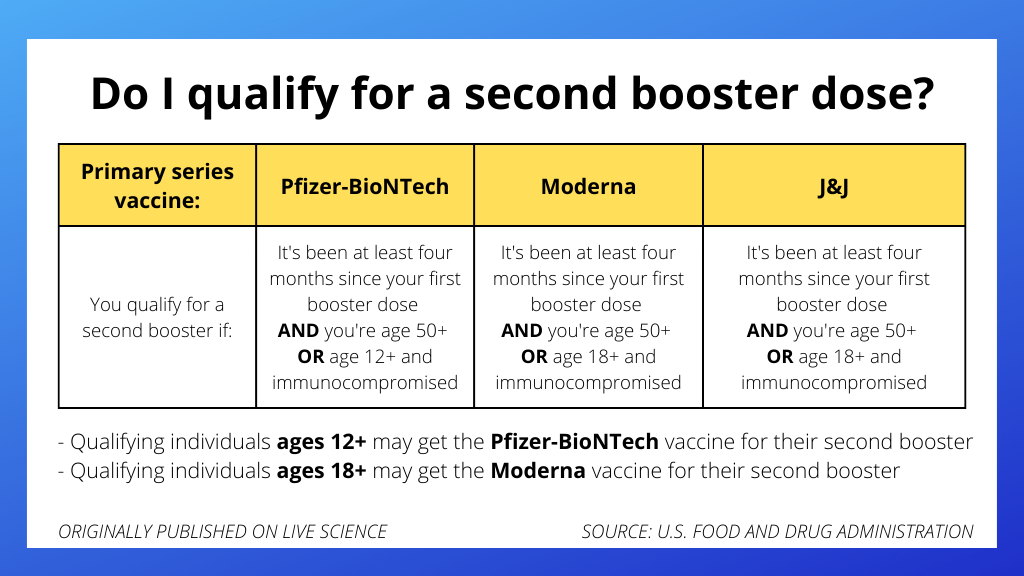

Last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized second booster doses of the COVID-19 vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. This authorization applies to individuals age 50 and older, as well as certain immunocompromised people ages 12 and older.

Dr. Rochelle P. Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said that second boosters are "especially important for those 65 and older and those 50 and older with underlying medical conditions that increase their risk for severe disease from COVID-19."

So if you qualify for a second booster, is it worth seeking one out right away? And are there any potential downsides to getting the shot now?

Broadly speaking, there's a consensus that extra boosters are safe and that people aged 65 and older and immunocompromised people of all ages would benefit most from a second booster shot, John P. Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, told Live Science.

"I think where there's differences of opinion is for healthy people in their 50s," Moore said.

Moore stressed that he is not a physician and therefore can't offer medical advice, but he's of the opinion that healthy individuals in their 50s can get the extra booster now if they want, but it's not necessarily a priority for them.

Related: Quick guide: Most widely used COVID-19 vaccines and how they work

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Who qualifies for a second booster?

Anyone age 50 and older can receive a second booster dose of either mRNA vaccine — Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna — if it's been at least four months since their first booster dose of any authorized or approved COVID-19 vaccine, the FDA said.

Younger people (those over age 12 for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, or those over age 18 for the Moderna vaccine) can also get a second booster dose if they have conditions that impair their immune response.

"These are people who have undergone solid organ transplantation," which involves being placed on immune-suppressing drugs, "or who are living with conditions that are considered to have an equivalent level of immunocompromise," the FDA said.

What are the benefits of the booster?

The FDA justified its authorization of second booster shots based on several studies conducted in Israel.

One study, posted Feb. 1 to the preprint database medRxiv, included more than a million people age 60 or older who had either received one booster shot or two. The follow-up time was very short — only 12 days — but suggested that the rate of severe disease was about four-fold lower in the double-boosted group, Eric Topol, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, wrote in a blog post last week.

Another study from Israel, posted on March 24 to Nature's preprint database, included more than 560,000 people ages 60 and older, and showed that those who received a second booster had a 78% lower death rate from COVID-19 compared with those who only received one booster.

Related: Coronavirus variants: Facts about omicron, delta and other COVID-19 mutants

But how long this boost in protection lasts is an open question.

"The deficiency in our knowledge base is the lack of follow-up, maximal at only 40 days so far, for enhanced protection vs. severe illness, hospitalization and death," Topol noted in his blog.

As these people are followed over time, we should know how long the enhanced protection lasts — and there should also be more data on younger people available soon, he noted.

Are there any safety risks?

The available data suggest that second booster shots don't come with any notable safety concerns, according to the FDA.

The Ministry of Health of Israel sent the FDA a summary of safety surveillance data collected from about 700,000 people — mostly over age 60 — who received second booster doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine at least four months after their first booster doses. This analysis "revealed no new safety concerns," the FDA noted.

The safety of the Moderna second booster was "informed by experience with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine and safety information reported from an independently conducted study," the FDA said. This small study included 120 adult participants who received a first booster dose of Pfizer-BioNTech and then a second booster of Moderna. "No new safety concerns were reported during up to three weeks of follow up after the second booster dose," the FDA said.

Who should get the booster ASAP, and who can wait?

Regarding who should get the shot now, Topol wrote in his blog that he would recommend a second booster if it's been more than 4 to 6 months since your last booster dose and "you are age 50+, you tolerated the previous shots well, and you are concerned about the BA.2 wave where you live, or that it's getting legs as you are trying to decide. Or if you are traveling or have plans that would put you at increased risk." (BA.2 is an omicron subvariant that spreads more easily than the original omicron, known as BA.1.)

Related: 'Stealth' omicron is in the US. Here's what we know about it.

But it's reasonable for some eligible individuals to put off getting a second booster, Topol wrote. For example, he said it's "fine to wait if there's a low level of circulating virus where you live and work." You can check the case positivity rate in your county or state using the CDC's COVID Data Tracker; the tracker also shows the number of new COVID-19 cases, hospital admissions and deaths.

What about those who had an omicron breakthrough case? For those who've had three doses of an mRNA vaccine and an omicron infection, there's little need for a second booster right now, Topol wrote.

Should you wait for an omicron-specific booster?

So far, data suggests you shouldn't wait for an omicron-specific booster.

Scientists have been studying variant-specific boosters in mice and rhesus macaques, a type of monkey. Animals in these studies were exposed to the omicron variant after being boosted with either another dose of one of the original mRNA vaccines or the new, omicron-specific shot, Moore told Live Science. The omicron-specific boosters offered the same amount of protection as the original vaccine formulas.

"The differences were subtle to unimportant," Moore told Live Science.

These studies were in animals though, so it remains to be seen whether an omicron-specific booster could offer people any added benefit over a normal booster, Topol wrote. Human trials of such boosters are ongoing.

Even if omicron-specific boosters do wind up working better than those against the original strain, "from my discussions with FDA, it is not likely the Omicron-specific vaccine will be available before late May or June," Topol wrote. "So you can factor that uncertain added benefit and timeline into your decision" to get a second booster sooner or later.

Will boosters now make future shots less effective?

Some people may be concerned that getting a second booster against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 could sabotage their immune system's attempts to ward off future coronavirus variants. So far, there's no evidence that receiving multiple booster doses against the same variant would have this undermining effect.

It is true that some experts have raised concerns about a phenomenon called "original antigenic sin," in which the immune system's first exposure to a pathogen, whether through infection or vaccination, leaves a permanent "imprint" and shapes the immune response to similar germs in the future. For example, a first encounter with an influenza virus in childhood can affect how well the immune system responds to later flu infections or the yearly flu shot, Live Science previously reported.

Could original antigenic sin — also known as "immune imprinting" or "antigen imprinting" — influence how the immune system responds to future SARS-CoV-2 variants and variant-specific boosters? Studies hint that yes, a person's first COVID-19 infection or vaccination leaves some impression on the immune system, whether that hinders the immune response to new variants or boosters in the future is unclear.

"I've not been convinced that original antigenic sin is an issue here," Moore said.

Related: Omicron's not the last variant we'll see. Will the next one be bad?

Thankfully, even though the current vaccines prime the immune system to react strongly tot the original SARS-CoV-2 variant, they still generate a range of antibodies that can latch onto multiple variants. By comparison, antibody responses to natural infection are much more narrow, a Jan. 24 study in the journal Cell found..

There is a chance that a new variant may crop up that effectively bypasses first generation vaccine-induced immunity. But in that case, antigen imprinting may be less of an issue.

"My own take is that if a variant comes along that's horrific enough to show major immune evasion, that very property will make it something that a new vaccine booster is likely to be able to target usefully," drug discovery chemist Derek Lowe wrote in Science Magazine's In The Pipeline blog. In other words, a variant that looks drastically different from the original SARS-CoV-2 might be easier to take down with a new, specially designed booster.

"Omicron isn't it, though," he wrote. "It's different enough to be much faster-spreading, but it's similar enough for the current vaccines to still provide a huge amount of protection."

Will I need a third booster soon?

At this point, no one knows if or when the FDA might authorize an additional booster dose for those who have already received two.

Early trials of omicron-specific boosters are still underway, so it's not yet known whether those would offer an advantage over the first-generation boosters. While we await the results of those trials, more data should emerge about the benefits of the second booster doses in different populations.

Recent studies hint that, in general, the second booster dose may not offer as dramatic a bump in antibodies or as significant an increase in immune memory compared with the first booster dose. In general, this might hint that repeated booster doses may offer "diminishing results," The New York Times reported.

"From what we know so far, the third dose is likely to be the most important," Moore said, referencing the first mRNA booster. This first booster follows a key period of time where the immune system consolidates its memory of the virus and establishes immune cell training camps known as "germinal centers," according to Nature. The booster likely helps to cement this immunological memory while also broadening which features of the virus can be recognized by the immune system.

So will a third booster someday be necessary? For now, we don't know — and of course, the emergence of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant could complicate the question.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus