Your most distant cousin doesn't even have an anus

The nerve of those comb jelly pretenders.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The entire history of the animal kingdom is like a long highway, with different species exiting at different points to pursue their own evolutionary paths. And sea sponges got off at the highway's first exit, ending up in the most distant corner of the country.

Scientists recently compared the genetics of sponges with that of another unusual animal: comb jellies. They say their research, published March 19 in the journal Nature Communications, resolves a debate: Some biologists already considered sponges the most distant cousins of all other animals; others argued that comb jellies were the true "sister to all other animals."

The concept of evolution existed for about a century before anyone discovered DNA. Many of the ideas developed during that era still hold: Animals that share many traits likely diverged from common ancestors more recently — taking the same evolutionary route until that point. And two animals that share fewer traits likely diverged longer ago.

Humans and other great apes, for example, look and act alike. So it makes sense to assume they share relatively recent ancestors. People and dolphins look different and live very different lives, but they share some key traits — live birth, mammary glands and hair. So they're more like second or third cousins.

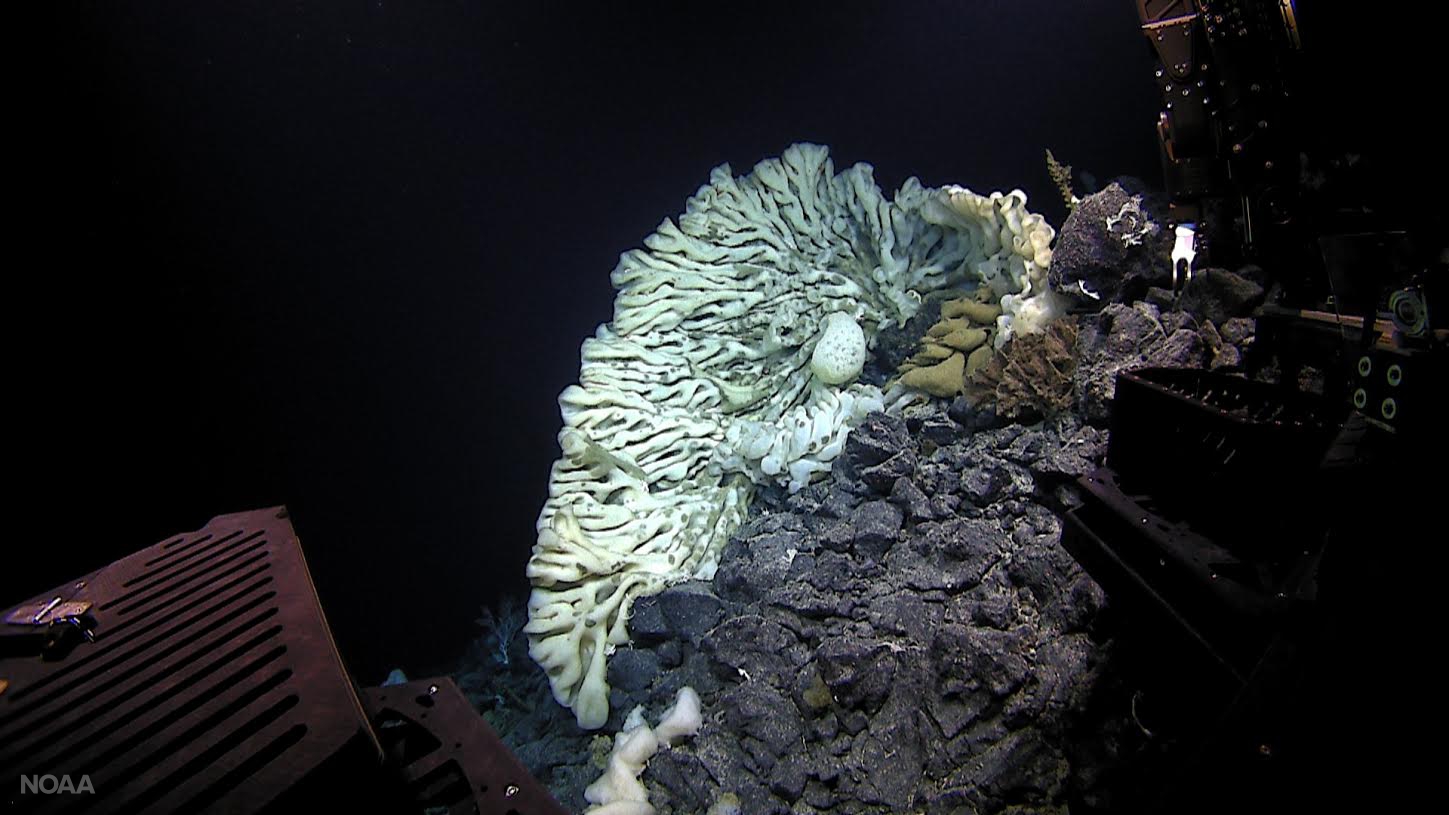

Taking this approach to the entire diversity of animals on Earth would suggest that sponges split off longest ago. They don't have muscles, nervous systems, organs or even the traditional mouth-to-anus digestive tract common to all other members of the animal kingdom. Their animal traits are basic: They're made of multiple cells, produce sperm, lack cell walls and need to eat for energy.

Related: 7 theories on the origin of life

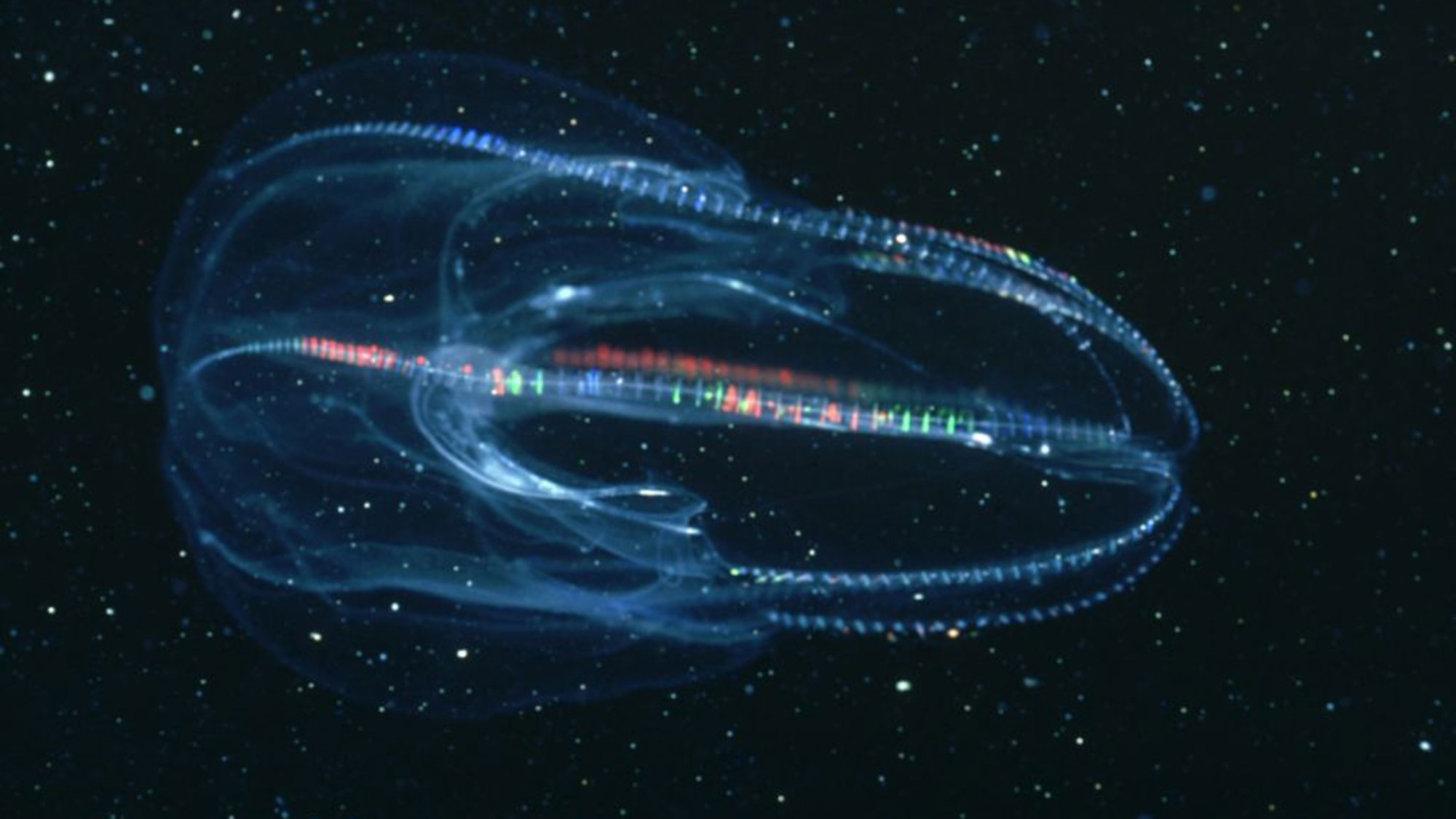

Comb jellies, which have muscles, simple anuses and nerves despite so many other differences from most animal life on Earth, seem to have diverged more recently — belonging to the same non-sponge branch of animal life as human beings, sea lions and tarantulas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This sort of analysis is useful but imperfect. Birds and bats both fly, but not due to any common ancestor; they evolved their wings independently, as Live Science previously reported. Manatees and whales are both water-dwelling mammals, but Live Science reported manatees are closer to elephants than ShamuIt seemed possible, based on earlier genetic work, that comb jellies split off from the rest of the animal kingdom before nervous system-less sponges did. As Live Science reported in 2017, most studies of relationships between animals look at their whole genomes. But this big-picture method is too imprecise to make fine distinctions between cousins as distant as sponges and comb jellies. So the most important sponge-comb studies rely on a handful of genes that all organisms share.

Even in these common genes, mutations creep in over time. The more mutations that separate two animals' common genes, the longer ago their evolutionary paths diverged. From this perspective, some scientists argued comb jellies and not sponges were the most distant cousins of other life. But that conclusion came from just a couple of genes that had diverged greatly in the comb jellies.

If comb jellies were the most distant cousins, that would be important. It would suggest comb jellies split off before nerveless sponges — and evolved their own nerves separately from other life. And if evolution invented the nervous system (or anus) twice, then maybe evolution really likes nervous systems (or anuses) for some reason. That would tell us something important about life itself.

This new paper throws cold water on that idea.

"Instead of comb jellies, our improved analyses point to sponges as our most distant animal relatives, restoring the traditional, simpler hypothesis of animal evolution," lead author and Trinity University microbiologist Anthony Redmond said in a statement.

The Trinity team developed a new method for studying the animals' genetics, taking into account the mechanisms of evolution itself. Genes contain instructions for building big, complex molecular machines known as proteins. When small pieces of a gene mutate — individual letters of genetic code swapping out for different units of code — those changes can result in proteins that don't do their job. So mutations that stick around tend to follow strict rules, changing the individual pieces of those proteins (known as amino acids) only in ways that don't usually cause the whole protein to stop working.

There are 20 amino acids in genetic code. That list of 20 breaks up into smaller "bins" of four to six biochemically similar amino acids that might, for example, share the same positive or negative charge.. A mutation that swaps one amino acid for another in the same bin is less likely to significantly change the behavior of a protein. Most mutations that stick around long enough to become part of a type of animal's genome involve swaps within bins.

Swapping an amino acid for a counterpart from a different bin is more likely to change the function of a protein. That means it's more likely to be harmful and therefore more likely to get weeded out through natural selection. Swaps of amino acids from different bins do happen, but it's much rarer that they stick around through the generations.

So, to simplify matters, if every additional swap of amino acids from the same bin means two species diverged a generation further in the past — great grandparents rather than grandparents — a mutation that swaps an amino acid for another from a different bin might suggest a hundred generations. Accounting for the differences between types of mutations when studying sponge and comb jelly genomes suggests sponges, not jelly combs, diverged first from the rest of animal life.

While jelly combs do have those couple of genes that are radically divergent from other animals, suggesting they diverged long ago in the deep past, a more holistic look at the types of mutations present in their genomes suggests a more recent diversion than the one sponges took. Nerves, anuses, and other common features of non-sponge animal life likely only evolved once.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus