Trippy satellite map of North America's largest glacier shows off 'hidden lagoon' and other secrets

NASA has revealed a new false-color image of Alaska's Malaspina Glacier that highlights several recent findings about the massive ice mass.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

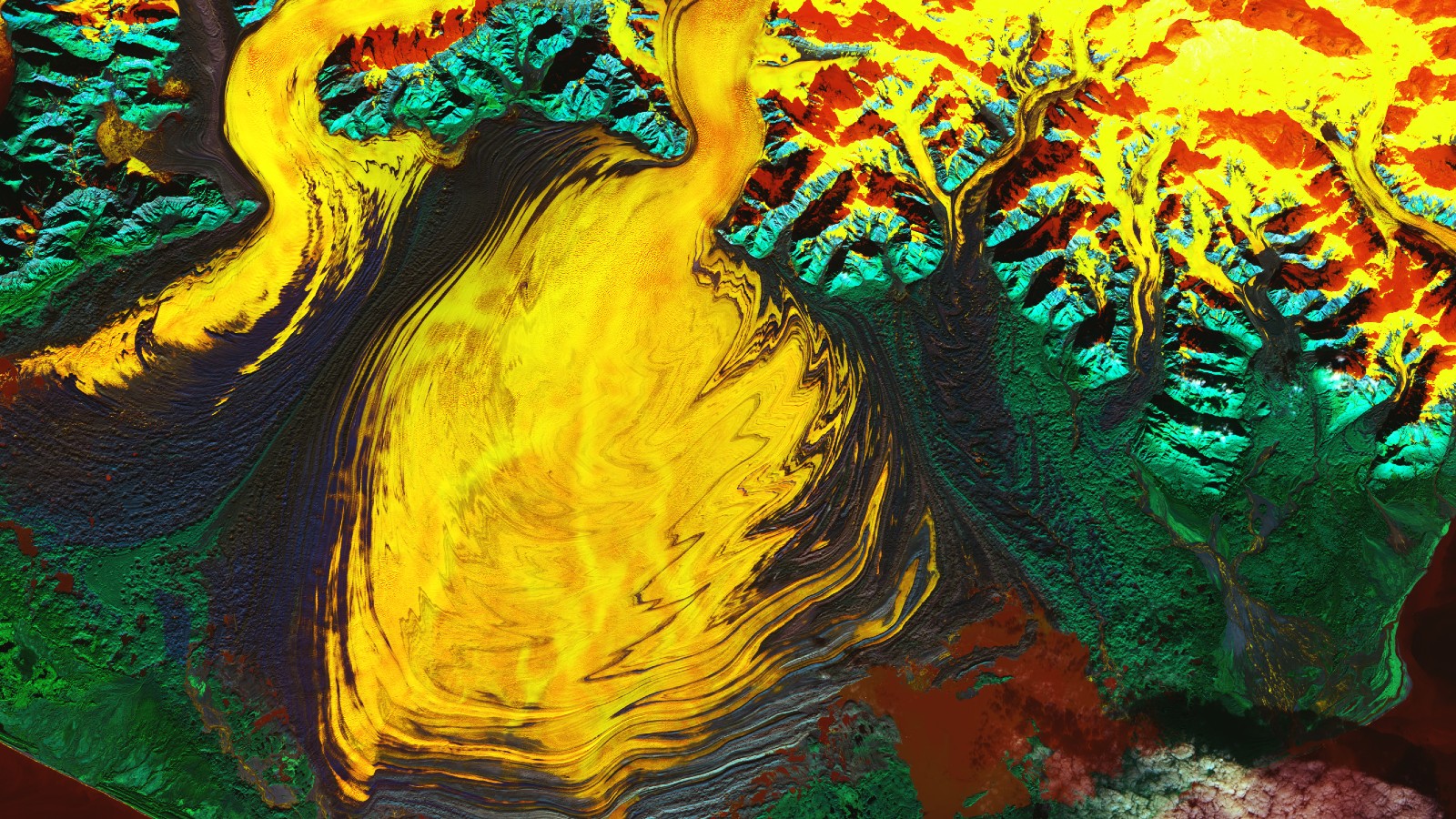

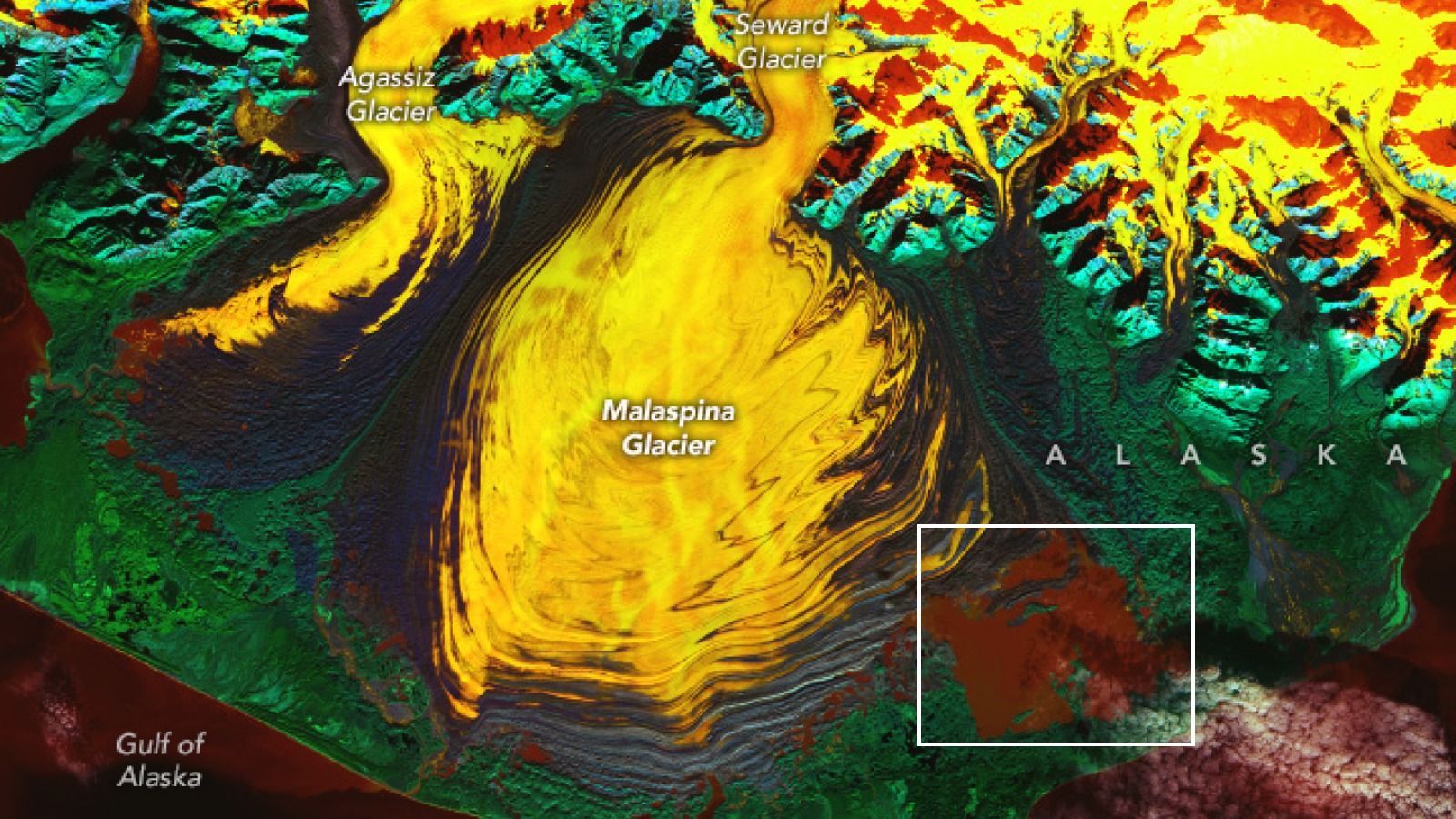

NASA has released a trippy, technicolor satellite photo of Alaska's Malaspina Glacier, which makes the massive ice mass look like a fiery, rippling blob of paint. The new image highlights recent discoveries at the glacier, including a "hidden lagoon."

The glacier, in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park on the state's southeastern coast, covers around 1,680 square miles (4,350 square kilometers), making it North America's largest glacier and the world's largest piedmont glacier — a type of lobed glacier that spills out from mountains onto flattened ground.

Malaspina Glacier is also known as Sít' Tlein, which means "big glacier" in the Tlingit language spoken by the Indigenous people in the area.

The image was captured on Oct. 27 by the Landsat 9 satellite, which is co-owned by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey. It was released by NASA's Earth Observatory on Nov. 25.

The picture is a false-color image created using infrared radiation. The yellow and orange colors represent ice; the red hues show water; and the blue and green colors show where land and vegetation occur, respectively. The ripples, or folds, in the ice are moraines — bands of soil, rock and other debris that are scraped up as the glacier slowly lurches forward.

Related: Landsat satellites: 12 amazing images of Earth from space

The Seward Glacier, which feeds into the Malaspina Glacier from the Saint Elias Mountains, and the Agassiz Glacier, which is fed by the same mountain range, are also visible in the image.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In February, a study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface revealed that the volume of the Malaspina Glacier's ice had previously been overestimated by around 30% — but if the entire ice mass were to melt away, it could raise the global average sea level by 0.06 inch (1.4 millimeters), the studys showed.

The study also revealed that the dark-red patch of water, located between the ice and an outstretched piece of land at the end of the glacier, is a saltwater lagoon that was hiding in plain sight. The lagoon is warmer than scientists previously suspected because of its high salt content, which could accelerate the ice melt rate.

The researchers also found that there are subglacial channels of water that run through the bedrock beneath the glacier. These channels extend up to 22 miles (35 kilometers) under the ice and could further accelerate the glacier's retreat.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus