Greenland's glaciers are melting 100 times faster than estimated

Scientists are getting a better handle on how fast Greenland's ice is flowing out to sea. Old models that used Antarctica as a baseline were way off the mark.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

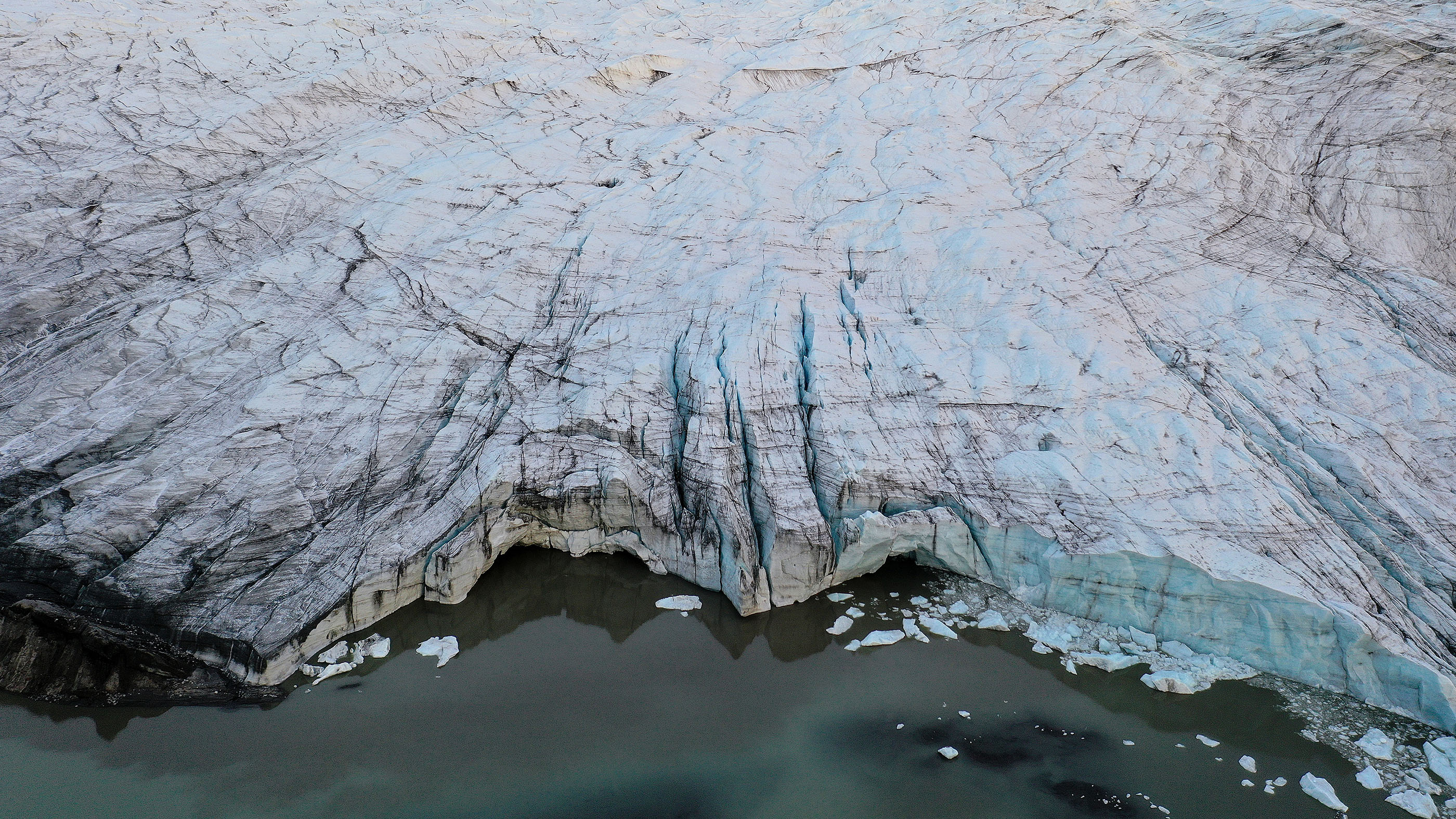

Greenland's glaciers are melting 100 times faster than previously calculated, according to a new model that takes into account the unique interaction between ice and water at the island’s fjords.

The new mathematical representation of glacial melt factors in the latest observations of how ice gets eaten away from the stark vertical faces at the ends of glaciers in GGreenland. Previously, scientists used models developed in Antarctica, where glacial tongues float on top of seawater — a very different arrangement.

"For years, people took the melt rate model for Antarctic floating glaciers and applied it to Greenland's vertical glacier fronts," lead author Kirstin Schulz, a research associate in the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences at University of Texas at Austin, said in a statement. "But there is more and more evidence that the traditional approach produces too low melt rates at Greenland's vertical glacier fronts."

The researchers published their findings in September in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Researchers already knew their Antarctica-based understanding of Arctic glaciers was not a perfect match. But it's hard to get close to the edges of Greenland's glaciers, because they're situated at the ends of fjords — long, narrow inlets of seawater flanked by high cliffs — where warm water undercuts the ice. This leads to dramatic calving events where chunks of ice the size of buildings crumble into the water with little warning, creating mini-tsunamis, according to the researchers.

Researchers led by physical oceanographer Rebecca Jackson of Rutgers University have been using robotic boats to get close to these dangerous ice cliffs and take measurements. They've done this at Alaska's LeConte Glacier as well as Greenland's Kangerlussuup Sermia. (An upcoming mission led by scientists at the University of Texas at Austin will send robotic subs to the faces of three west Greenland glaciers.) Jackon's measurements suggest that the Antarctica-based models massively underestimate Arctic glacial melt. LeConte, for example, is disappearing 100 times faster than models predicted.

The mixture of cold fresh water from the glaciers and warmer seawater drives ocean circulation near the glaciers and farther out in the ocean, meaning the melt has far-reaching implications. The Greenland ice sheet is also important for sea-level rise; Greenland ice holds enough water to raise sea levels by 20 feet (6 meters).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new model uses the latest data from near-glacial missions along with a more realistic understanding of how the steep, cliff-like faces of the glaciers impact ice loss. The results are consistent with Jackson's findings, showing 100 times more melt than the old models predicted.

"Ocean climate model results are highly relevant for humankind to predict trends associated with climate change, so you really want to get them right," Schulz said. "This was a very important step for making climate models better."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus