Surprise discovery of world's 2nd deepest blue hole could provide window into Earth's history

The second deepest blue hole in the world has been discovered off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. The giant, underwater cavern is around 900 feet deep and spans an area of 147,000 square feet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

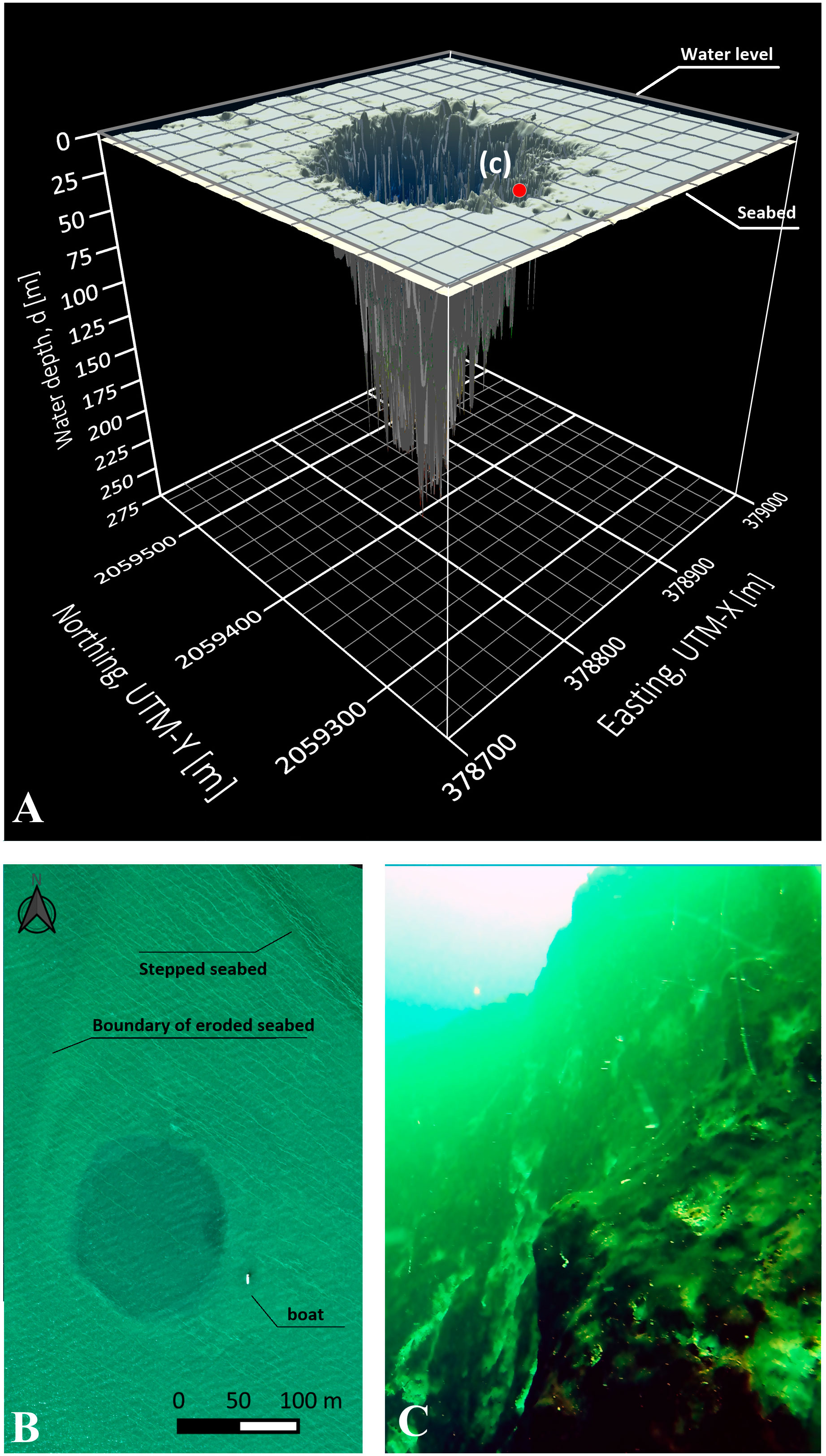

The second deepest blue hole in the world has been discovered off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. The giant, underwater cavern, located in Chetumal Bay, is around 900 feet (274 meters) deep and spans an area of 147,000 square feet (13,660 square meters).

That's just shy of the record set by the world's deepest known blue hole — the Dragon Hole in the South China Sea — which was discovered in 2016 and is thought to be more than 980 feet (300 m) deep.

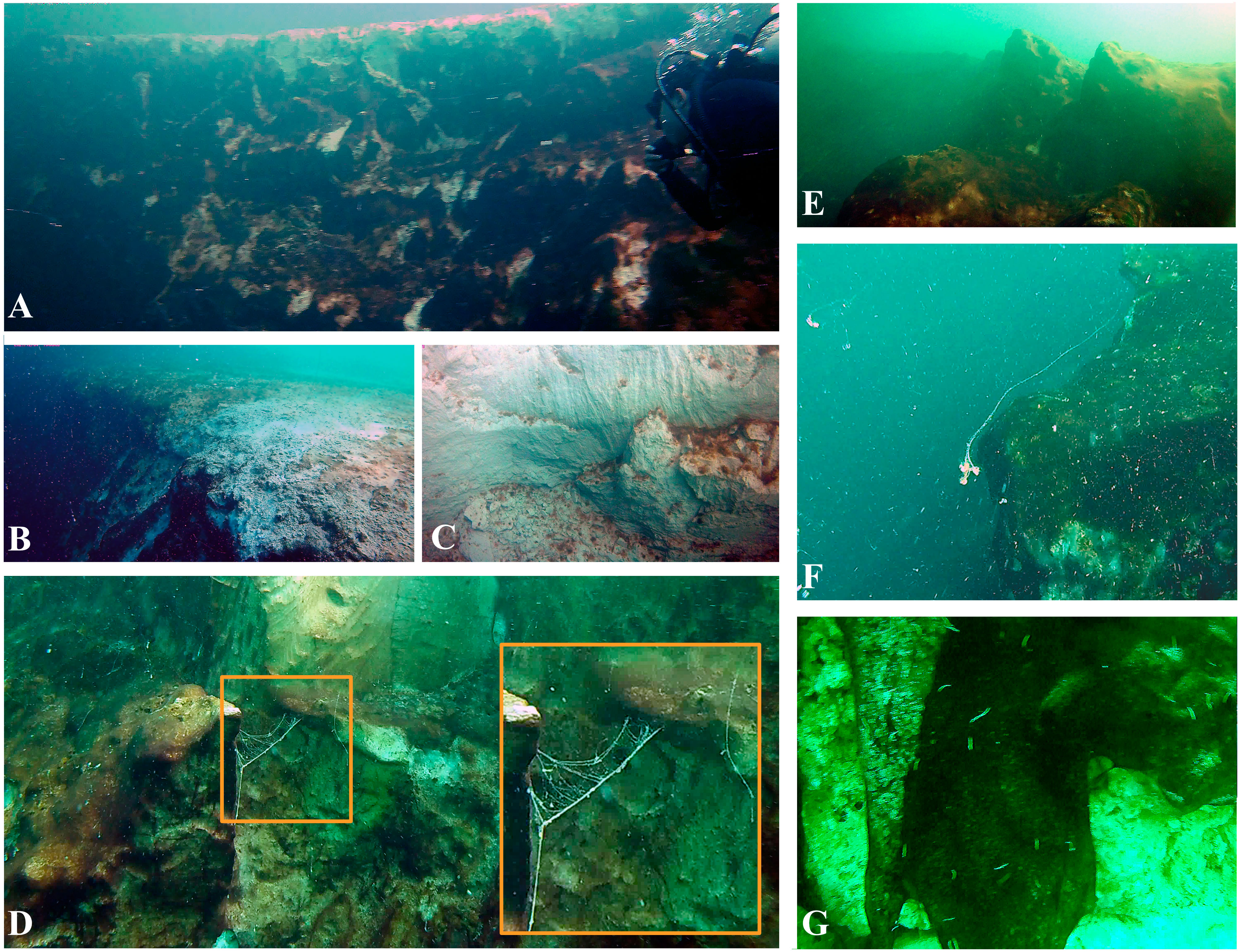

Blue holes are large, undersea vertical caves or sinkholes found in coastal regions. Many contain a high diversity of plant and marine life, including corals, sea turtles and sharks. The one in Chetumal, named Taam Ja’ which means "deep water" in Mayan, has steep sides with slopes of almost 80 degrees, and the mouth of the cavern sits around 15 feet (4.6 m) below sea level. Scientists from El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Ecosur), a public research center coordinated by Mexico's National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt), first discovered it in 2021. A study of the find was published Feb. 23 in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Blue holes form when sea water meets limestone. Limestone is very porous, so water easily permeates the rock, enabling chemicals in the water to react with the limestone, eating it away. Many of the world's blue holes likely formed during past ice ages, when the repeated flooding and draining of coastal areas eroded the rock and created voids. When the last ice age ended around 11,000 years ago and sea levels rose, these caverns filled with water and some were completely immersed.

Related: Strange 'alien' holes discovered on the ocean floor

Because blue holes are so hard to reach, scientists haven't studied many of them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“They are largely poorly understood,” Christopher G. Smith, a coastal geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) who has studied other submarine sinkholes but was not involved in the latest research, told Live Science in an email. Smith added that the unique seawater chemistry in blue holes suggests they may interact with groundwater and possibly aquifers — bodies of rock or sediment that hold groundwater.

Blue holes contain little oxygen, and sunlight only shines on the surface. Despite these conditions, the gigantic voids are teeming with life that has adapted to the low-oxygen environment.

Blue holes may offer a snapshot of what life was like thousands of years ago. Without much oxygen or light, fossils can be well-preserved, enabling scientists to identify the remains of extinct species, the researchers noted in the study.

Blue holes may also tell us more about life on other planets. In 2012, researchers peering into blue holes in the Bahamas found bacteria deep in the caverns where no other lifeforms dwelled. Such findings could offer clues as to what life may exist in the extreme conditions elsewhere in our solar system.

Lydia Smith is a health and science journalist who works for U.K. and U.S. publications. She is studying for an MSc in psychology at the University of Glasgow and has an MA in English literature from King's College London.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus