Astronomers discover enormous 'cavity' in the Milky Way being masked by a cosmic illusion

The bubble-shaped void is likely the result of an ancient supernova shockwave.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two clouds of gas, both alike in dignity, appear side by side in the fair Milky Way. Known as "molecular clusters," these enormous provinces of star-forming gas stretch across the sky, seeming to form a bridge between the Taurus and Perseus constellations where new suns can grow and thrive for billions of years to come.

It's a celestial tale of star-crossed love — and, according to new research, it's also an enormous optical illusion.

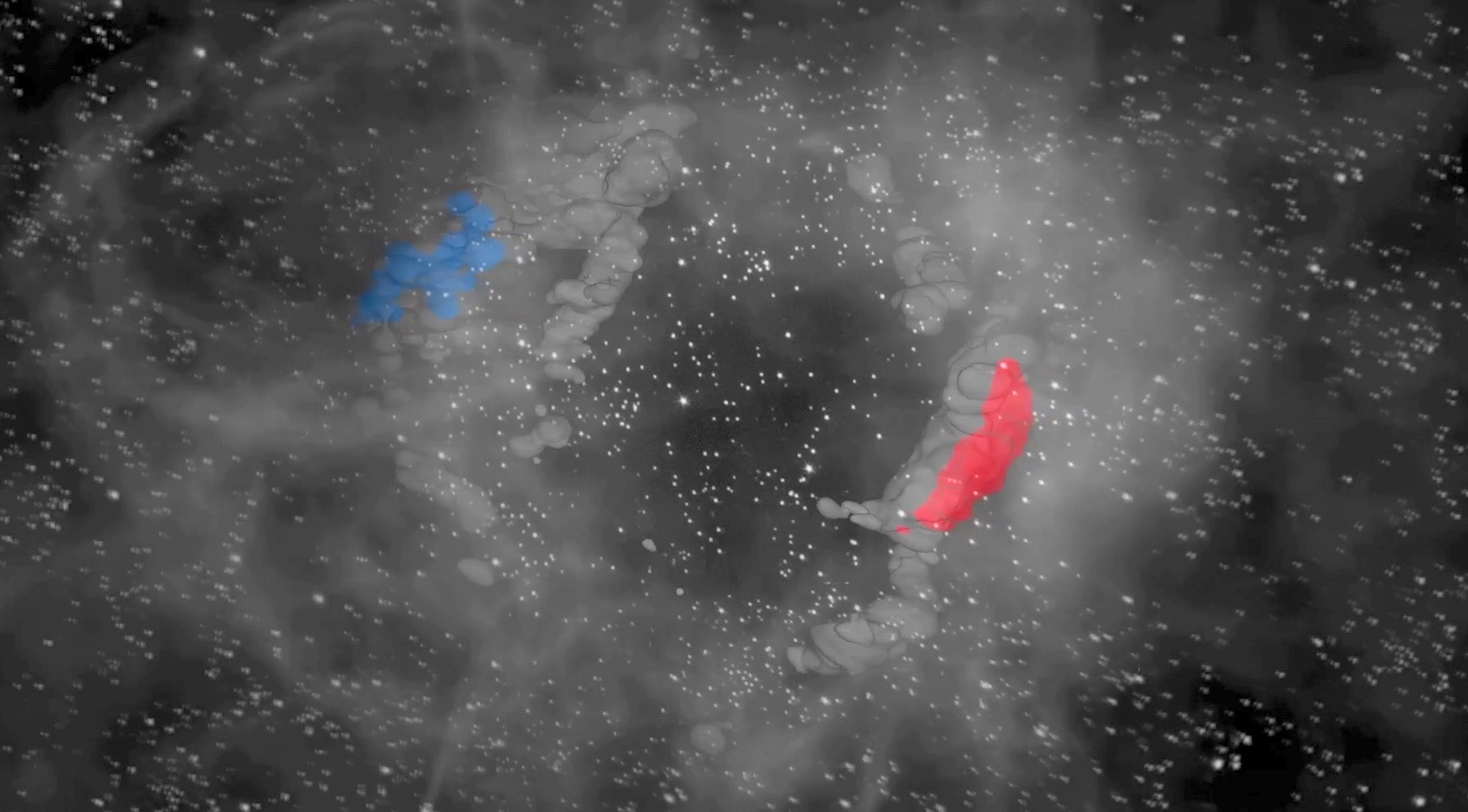

New 3D maps of the region, created with help from the European Space Agency's Gaia space observatory, show that these canoodling clouds are actually hundreds of light-years apart — separated by an enormous, empty orb where neither gas, nor dust nor stars can find purchase.

Dubbed the Perseus-Taurus Supershell, this newly detected chasm stretches about 500 light-years wide, according to a study published Sept. 22 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters — or roughly 115 times the distance between Earth and the nearest alien sun, Proxima Centauri. While hundreds of young stars have already formed around the edges of the bubble, the great, spherical emptiness within points to one obvious culprit, the authors wrote: a catastrophic supernova explosion.

"Either one supernova went off at the core of this bubble and pushed gas outward forming what we now call the 'Perseus-Taurus Supershell,', or a series of supernovae occurring over millions of years created it over time," lead study author Shmuel Bialy, a postdoctoral researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said in a statement.

Astronomers have known about the Taurus and Perseus molecular clouds for decades, but all prior research was based on two-dimensional observations. Now, with data from Gaia, the study authors developed a new technique of mapping the dust in distant corners of the galaxy in 3D. (The authors describe their methods further in a second study, published Sept. 22 in The Astrophysical Journal.)

Upon mapping these seemingly linked clouds of gas, the researchers realized that there was no physical connection between them — but rather, they resided on opposite sides of an invisible, empty cavity. The long filament of gas that seemed to connect them is just a "coincidental projection" that resides on the closer, Taurus side of the bubble, and only appears to connect to the farther Perseus side, the team wrote in their study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Given the positions of the molecular clouds and the ages of the stars within them, the researchers estimated that both clouds formed as a result of the same supernova explosion about 10 million to 20 million years ago. Explosions like these occur when large stars run out of fuel, shed their outer layers of hot gas and then collapse under their own gravity. This sudden collapse creates a powerful shockwave, pushing all that leftover gas and dust far away from the ex-star's ramshackle remains.

In this case, two big blobs of gas seem to have congregated on opposite sides of the shockwave, where each one began to condense and form new stars, the researchers said.

"This demonstrates that when a star dies, its supernova generates a chain of events that may ultimately lead to the birth of new stars," Bialy said.

So, this story of star-crossed clusters has a hopeful ending after all. But the happier takeaway, according to the researchers, is the new mapping technique itself. This study represents the first time that molecular clouds have been imaged in 3D, and it opens the door to many potential discoveries about the way gas rearranges itself to form stars across the galaxy, the authors wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus