There's a Mysterious Source of Oxygen in Mars' Atmosphere, and No One Can Explain It

There's something strange about the oxygen in the atmosphere above Mars' Gale Crater: Its levels fluctuate dramatically as the seasons change. And this mysterious oxygen cycling can't be explained by any known chemistry, a new study found.

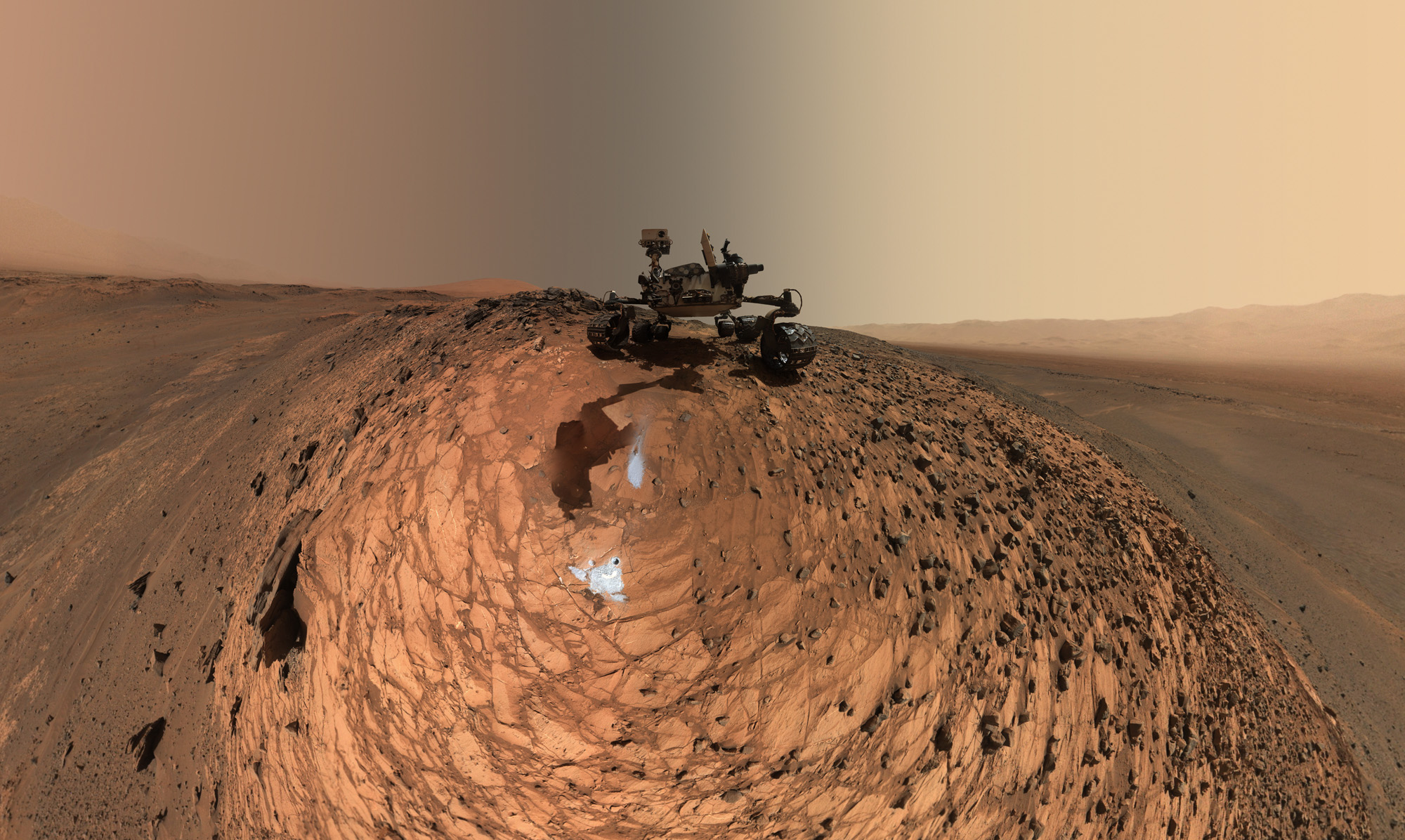

Gale Crater is a 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) depression that was created by a meteor crash 3.5 billion to 3.8 billion years ago. NASA's Curiosity rover has been exploring the crater since 2012, when it landed at the foot of Mount Sharp, a giant mountain at the heart of the crater, according to NASA.

For the past three Martian years (over five Earth years), the rover has been breathing in the air above Gale Crater and analyzing the atmosphere using an instrument called the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM), which is part of a portable chemistry lab, NASA officials said in a statement.

Related: Photos: Gale Crater on Mars

SAM confirmed that 95% of Mars' atmosphere is made up of carbon dioxide (CO2) and the other 5% is a combination of molecular nitrogen (two nitrogen atoms bound together), molecular oxygen, argon and carbon monoxide. SAM also found that, when CO2 gas freezes at the poles during the Martian winter, the entire planet's air pressure drops. When the CO2 evaporates in the warmer months, the air pressure rises again. Argon and nitrogen predictably rise and fall, depending on how much CO2 is in the air.

But when SAM analyzed the oxygen levels in the crater, the results were mystifying: The oxygen levels rose much higher than expected — as much as 30% of its baseline levels in the spring and summer — and then dropped to levels lower than predicted in the winter.

"We're struggling to explain this," lead author Melissa Trainer, a planetary scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in the statement. "The fact that the oxygen behavior isn't perfectly repeatable every season makes us think that it's not an issue that has to do with atmospheric dynamics" or any physical processes that happen in the atmosphere such as the breakup of molecules. All of the possible explanations they came up with fell short.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rather, "it has to be some chemical source and sink that we can't yet account for," she added.

This puzzle is reminiscent of a similar mystery about methane levels in the crater: SAM previously found that the typically indiscernible levels of methane sometimes increase by about 60% in the summer and plummet at other random times, for unknown reasons.

"We're beginning to see this tantalizing correlation between methane and oxygen for a good part of the Mars year," Sushil Atreya, a professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in the statement. "I think there's something to it." But nobody knows what that "something" is yet, he added.

Both oxygen and methane can be produced biologically (such as by microbes) and geologically (such as by water and rocks), and scientists don't know which process could be producing the elements in excess. However, to the disappointment of alien hunters, it's more likely that the excess oxygen and methane are the results of a geological process, according to the statement. Currently, the most likely source of the excess oxygen is the Martian soil, the team reported. But even if that's the case, they have no idea what in the soil is releasing so much oxygen into the atmosphere.

The findings were published Nov. 12 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

- Photos: Red Planet Views from Europe's Mars Express

- The 6 Most Likely Places to Find Alien Life

- These Are the Last Photos NASA's Opportunity Rover Took on Mars

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.