This Newly Discovered Virus Replicates in a Completely Unknown Way

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

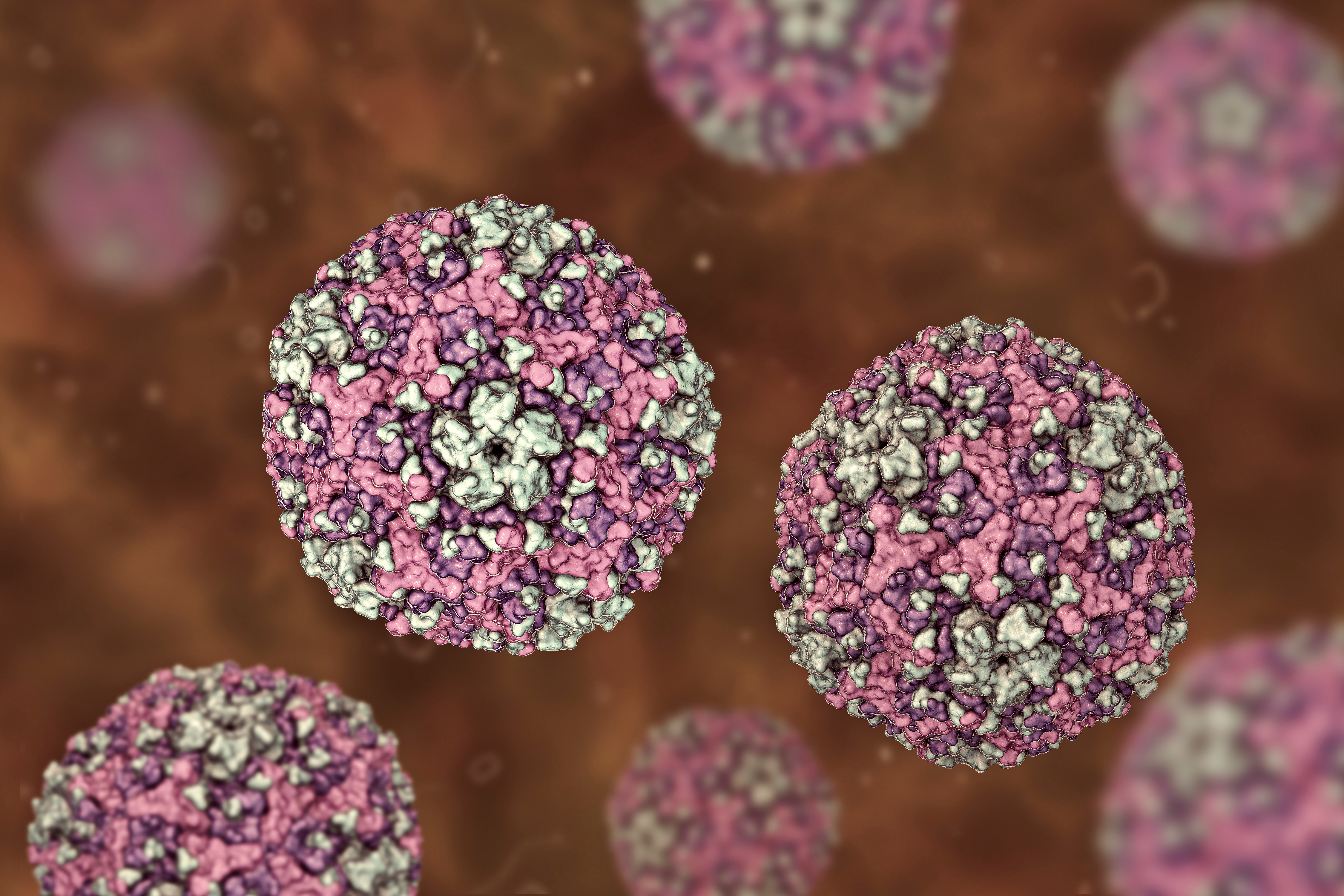

A newly discovered virus seems to lack the proteins needed to replicate itself. Yet somehow, it's thriving, according to a new study.

To find this mysterious virus, a group of researchers in Japan have spent nearly a decade analyzing pig and cow poop for novel viruses. These dirty environments, where lots of animals constantly interact, are a good place for viruses to quickly evolve, according to a statement from Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology in Japan.

Related: 27 Devastating Infectious Diseases

The researchers have found on farms several novel viruses that have recombined — meaning that two or more viruses have swapped genetic material. But they were particularly intrigued when they found a new type of enterovirus G (EV-G), which is composed of a single strand of genetic material. This new virus was formed from an enterovirus G and another type, called a torovirus.

Mysteriously, the newly discovered microbe lacks a feature present in all other known viruses — so called “structural proteins” that help the parasite attach to and enter host cells, then replicate. Though the new enterovirus lacks the genes that code for these structural proteins, it does have a couple of "unknown" genes, according to the researchers.

"This is very strange," senior author Tetsuya Mizutani, the director at the Research and Education Center for Prevention of Global Infectious Disease of Animal (TUAT) in Japan, told Live Science in an email.

Without structural proteins, the virus shouldn't be able to infect other cells, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Yet, three years later, the researchers found the same virus in pig poop on the same farm, suggesting that the virus did replicate in pigs. The scientists analyzed poop they gathered from other farms and also found this virus present.

So, how does the virus, which they named type 2 EV-G, survive? Mizutani and his team hypothesize that the virus borrows structural proteins from other nearby viruses, called "helper viruses."

That’s not totally unheard of. Hepatitis D virus needs the hepatitis B virus to replicate in the body, though it does have its own structural proteins, said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist and a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, who wasn't involved with the study.

"Understanding how viral recombination occurs and how viruses develop dependencies on helper viruses is an important key to unlocking some of the mysteries of virus evolution," Adalja told Live Science.

There are now over 30 virus families in the world, which likely evolved from one or a few common ancestors, Mizutani said. It's clear that they didn't all evolve from random mutations in their genomes, but rather combined with each other, just as the ancestors of type 2 EV-G did, he added. Now, Mizutani and his team hope to figure out which helper viruses enable 2 EV-G to survive, and exactly what the unknown genes do.

The findings were published on July 22 in the journal Infection, Genetics and Evolution.

- 5 Weird Ways Hot Tubs Can Make You Sick

- 7 Absolutely Horrible Head Infections

- 10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus