Parade of life-size camel carvings in northern Arabia date to the Stone Age

A parade of life-size stone camel carvings in northern Arabia dates back to the Stone Age, new research finds.

The 21 camels and horse-like figures were found in 2018 in the province of Al-Jouf in the northwestern Saudi desert. Researchers first believed that the carvings were about 2,000 years old, in part because they look similar to rock reliefs found in the famous stone city of Petra in Jordan.

New dating efforts reveal that the carvings are much older: They date back 8,000 years. They were probably carved between 6000 B.C. and 5000 B.C., when the region was wetter and cooler. At the time, the landscape was a grassland punctuated with lakes, where camels, horses and their relatives roamed wild, the researchers said. Humans herded flocks of cattle, sheep and goats -- and apparently created great works of art.

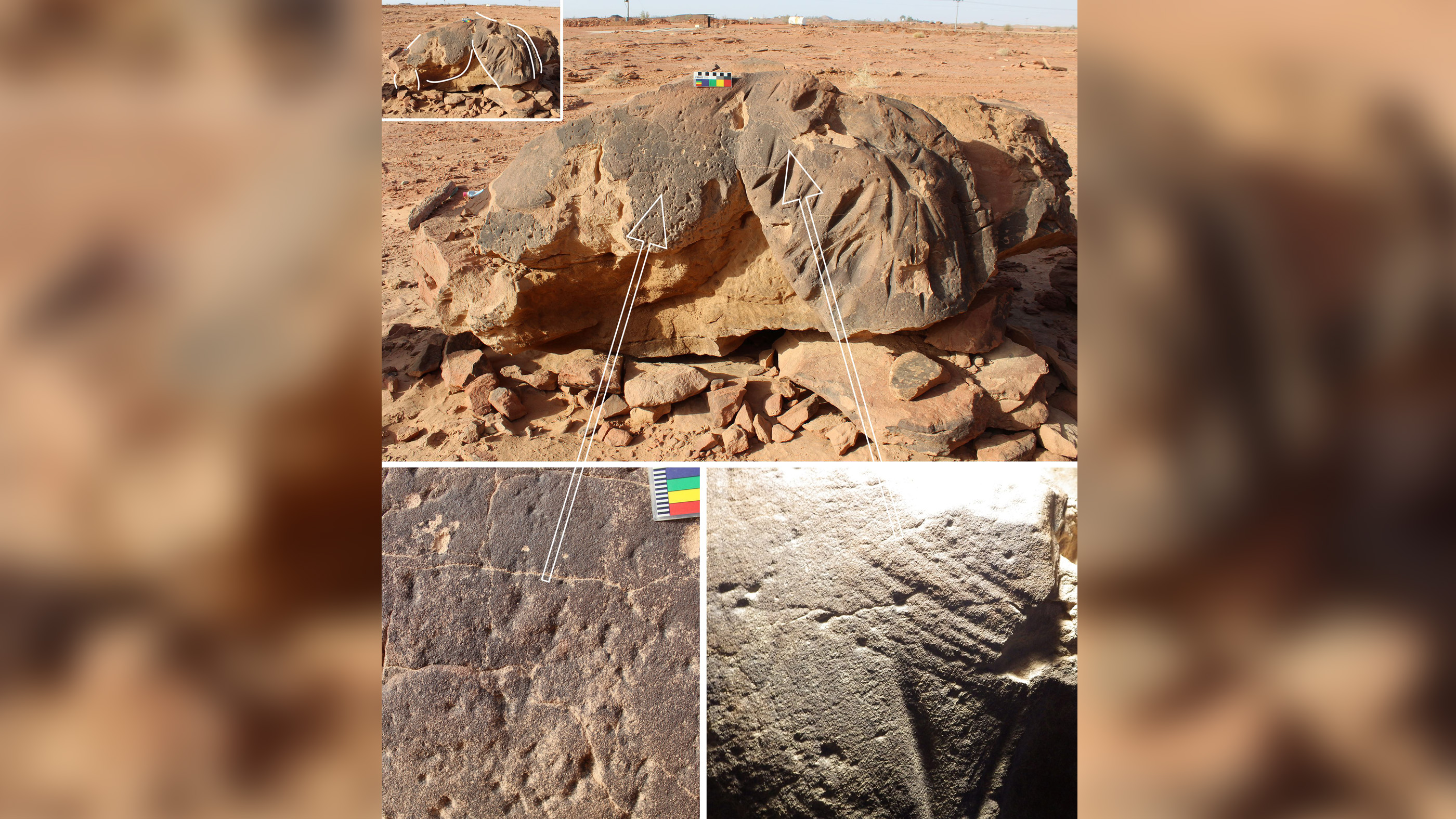

The carvings are chiseled into naturally occurring rocks at the site, and they often seem to meld with the natural grain of the rock. Their creation would have required tools made of a stone called chert, which would have come from at least 9 miles (15 kilometers) away. Artists who took on the laborious job of carving each animal would have needed some sort of scaffolding and a couple of weeks' time to complete, according to researchers from the Saudi Ministry of Culture, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the Centre national de la recherche scientifique in France and King Saud University.

Related: See photos of mysterious stone structures in Saudi Arabia

"Neolithic communities repeatedly returned to the Camel Site, meaning its symbolism and function was maintained over many generations," said Maria Guagnin, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Science of Human History, who led the new research. The study was published Wednesday (Sept. 15) in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports.

The carvings are quite eroded, meaning that dating them was difficult. The researchers used multiple lines of evidence to do so, ranging from the tool marks in the rock to radiocarbon dating of bones found in related rock layers. (Radiocarbon dating uses the radioactive decay of certain carbon molecules to mark time, but it requires organic material for the analysis.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also measured the density of the desert varnish on the rocks using a technique called portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Desert varnish is a mineral coating that forms on desert rocks over time. Portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry uses a handheld device to beam X-rays at a sample and non-destructively analyze the elements on its surface. Finally, the team used luminescence dating of fragments that had fallen off the rock wall to determine when those fragments fell. This method measures the amount of naturally occurring radiation in rocks and can reveal when a rock was first exposed to sunlight or intense heat and how long it's been acquiring radiation from the sun since that time.

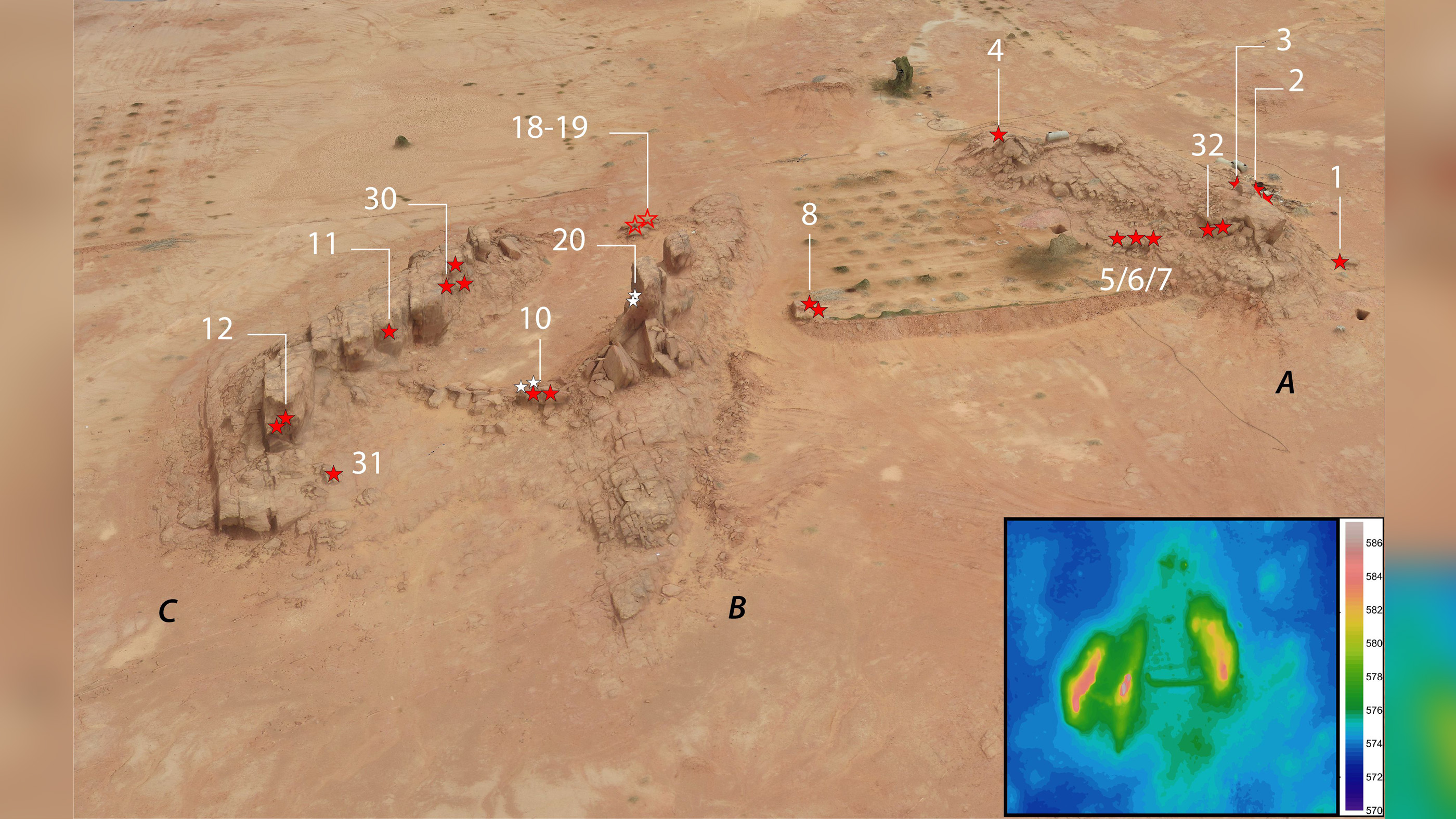

The new Neolithic, or Stone Age, date, puts the carvings in the context of other rock art made by pastoral people in northern Arabia, the researchers said in a statement. These include large stone monuments called mustatil, which are made of sandstone walls surrounding a courtyard with a stone platform at one end.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.