Scientists discover 200 'Goldilocks' zones on the moon where astronauts could survive

Scientists discover pits on the moon that are room temperature in the shade.

Lunar scientists think they've found the hottest places on the Moon, as well as some 200 Goldilocks zones that are always near the average temperature in San Francisco.

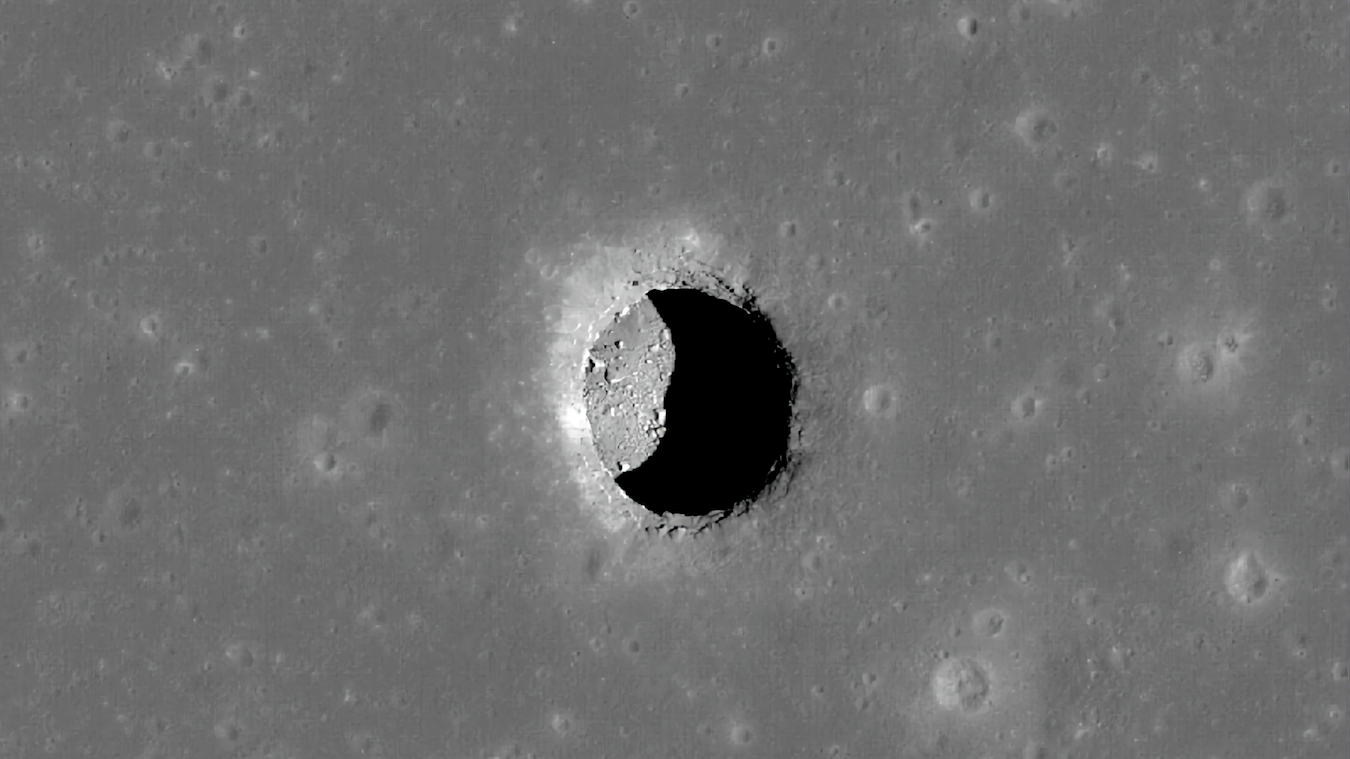

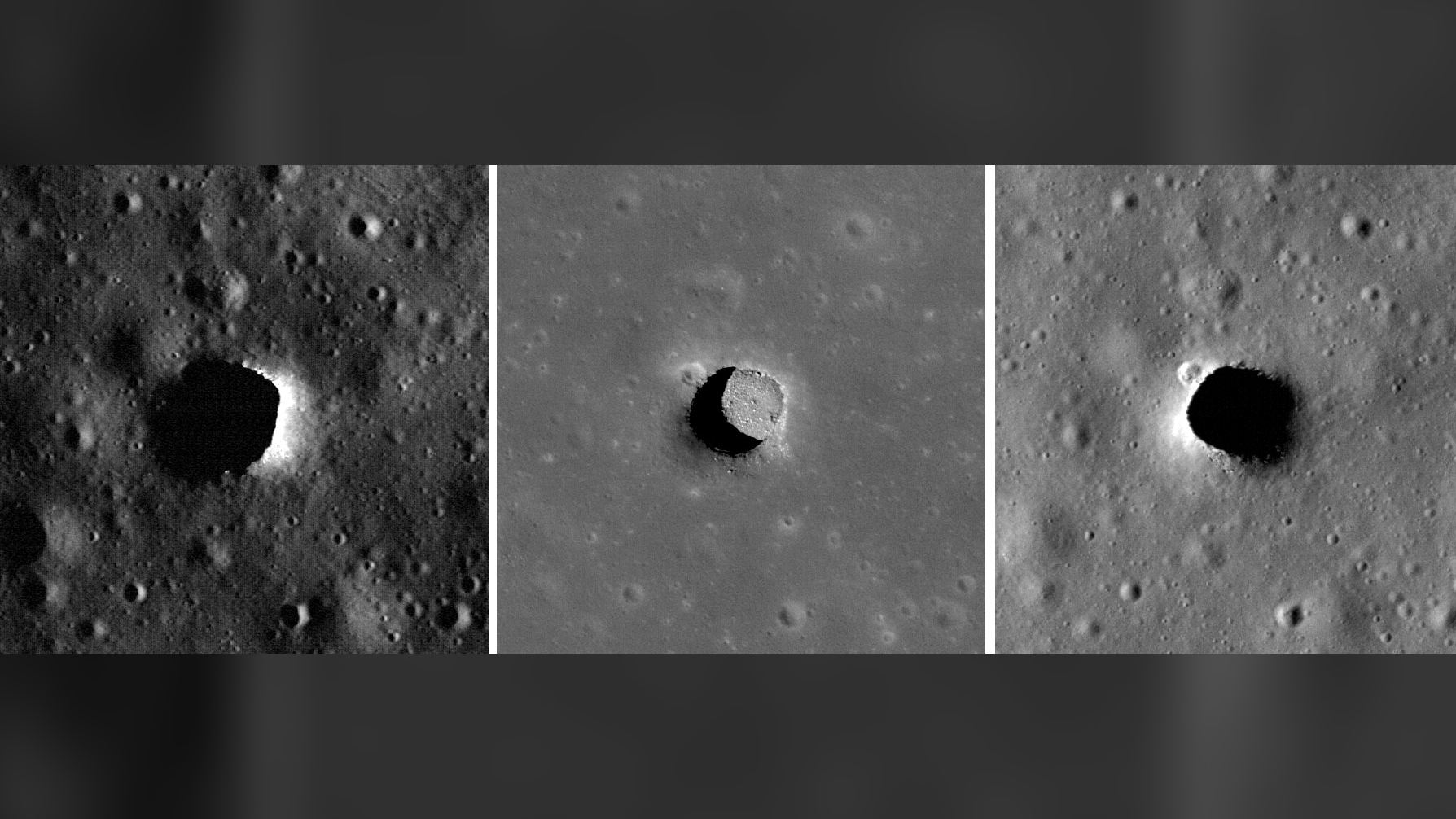

The moon has wild temperature fluctuations, with parts of the moon heating up to 260 degrees Fahrenheit (127 degrees Celsius) during the day and dropping to minus 280 F (minus 173 C) at night. But the newly analyzed 200 shaded lunar pits are always always 63 F (17 C), meaning they're perfect for humans to shelter from the extreme temperatures. They could also shield astronauts from the dangers of the solar wind, micrometeorites and cosmic rays. Some of those pits may lead to similarly warm caves.

These partially-shaded pits and dark caves could be ideal for a lunar base, scientists say.

"Surviving the lunar night is incredibly difficult because it requires a lot of energy, but being in these pits and caves almost entirely removes that requirement," Tyler Horvath, a doctoral student in planetary science at the University of California, Los Angeles and lead author on the NASA-funded research published online July 8 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, told Live Science.

Related: How many space rocks hit the moon every year?

It's a revelation that has been over a decade in the making. The first pit on the lunar surface was discovered in 2009 by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA) Kaguya (formerly SELENE, for SELenological and ENgineering Explorer) orbiter. However, this new work has been done using a thermal camera, the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment, on NASA's robotic Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO).

Of the 200 pits discovered, two to three have overhangs that lead to a cave, while 16 appear to be "'skylights"' to collapsed lava tubes. On Earth, lava tubes are hollow caves found close to the surface in volcanic regions — most notably Kazumura Cave in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and La Cueva del Viento on Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As the lava flowed, the top of it solidified while the lava continued to flow beneath it, in some places the lava actually evacuates completely and leaves a lava tube," Horvath said. If a lava tube collapses, a pit is created that acts as a "skylight" to a long cavity.

That same process happened billions of years ago when massive volcanic events on the moon created the famously dark lava fields on the lunar surface called "maria," which is Latin for seas.

"These pits likely formed due to small impacts punching a hole into the lava tube's ceiling or seismic activity weakening the ceiling," Horvath said.

In the new study, researchers analyzed the temperatures within a cylindrical pit about 328 feet (100 meters) deep in the Mare Tranquillitatis — the Sea of Tranquility — near the moon's equator. The team's findings revealed that while the pit's floor is illuminated at lunar noon, it's probably the hottest place on the entire surface of our natural satellite, at around 300 F (149 C); meanwhile, temperatures within the permanently shadowed reaches of the pit fluctuate only slightly from Earthlike hoodie temperatures.

The pit is relatively close to where two of NASA's Apollo missions landed. "The Tranquillitatis pit is actually the same distance from the Apollo 11 and Apollo 17 landing sites, about 375 kilometers [233 miles] away," Horvath said. "If we end up going there it would be incredible to see the bookends of the Apollo program and how well it's been preserved."

That's a possibility. The study was initially to help inform tentative plans for a Moon Diver mission proposed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 2020, which would have a rover descend into the Tranquillitatis pit to explore any existing cave. "This rover would be able to study the layers of lava flows in the pit walls that have been imaged by LRO, helping us better understand the moon's earlier history and evolution," Horvath said. "There's not a whole lot left to study about these pits from orbit, but there's plenty of opportunity if we go to one directly."

Apollo 11's "Tranquility Base" could yet get a subterranean sequel.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus