Astronomers Just Found the First Evidence That 'Mini Black Holes' Exist

An entirely new class of black holes may be lurking in the universe, and these may be far tinier than what scientists have found before, according to new findings.

Black holes are massive celestial objects that gobble up everything that comes too close; not even light can escape a black hole's intense gravitational grasp. The search for black holes, small and large — such as the supermassive ones that sit at the center of most galaxies, including our own — helps researchers piece together how the universe works and creates a narrative for the life and death of stars.

That's because black holes are the corpses of what used to be massive stars that underwent an explosive demise, ultimately collapsing in on themselves. The explosive death and subsequent collapse of stars can form two different objects. If the original star is massive enough, this explosion will yield a black hole, but if it's not, the corpse will instead form a small, dense object known as a neutron star.

Related: 9 Ideas About Black Holes That Will Blow Your Mind

Astronomers typically search for these black holes in our own galaxy by measuring X-rays that are emitted when black holes siphon material from nearby stars. In distant galaxies, on the other hand, researchers look for gravitational waves produced by the merging of two black holes or from a collision of neutron stars.

But a group of researchers wondered if there might be relatively low-mass black holes that don't emit the telltale X-ray signals of other black holes. Such hypothetical black holes would likely exist in a binary system with another star, though they would orbit far enough away from this star that they wouldn't eat much from their stellar companion; as such, the researchers surmised, these little black holes wouldn't give off detectable X-rays and so would remain invisible to astronomers, said Todd Thompson, a professor of astronomy at The Ohio State University and lead author of the study laying out the new findings.

"We're pretty sure that there must be many, many of these black holes in binary systems with stars out there in the galaxies, just that we haven't found them because they're hard to find," Thompson told Live Science. But "it's always interesting to try to find things that can't be seen."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Thompson and his colleagues looked for evidence of these black holes in the proposed objects' stellar companions. The researchers combed through data from the Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE) that had information on the light spectrum — the various wavelengths of energy produced by an object — from over 100,000 stars in our galaxy.

The information from this survey revealed changing spectra, or wavelengths of light, from each of those stars. If the researchers noticed any changes in these spectra — a shift toward bluer wavelengths or a shift to redder wavelengths, for example — it could mean that a particular star was orbiting an unseen companion. After doing this analysis, the researchers looked at the brightness changes of a subset of stars that could be orbiting black holes, using data from another survey called the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN). They searched for the stars that were brightening and dimming while also red-shifting and blue-shifting.

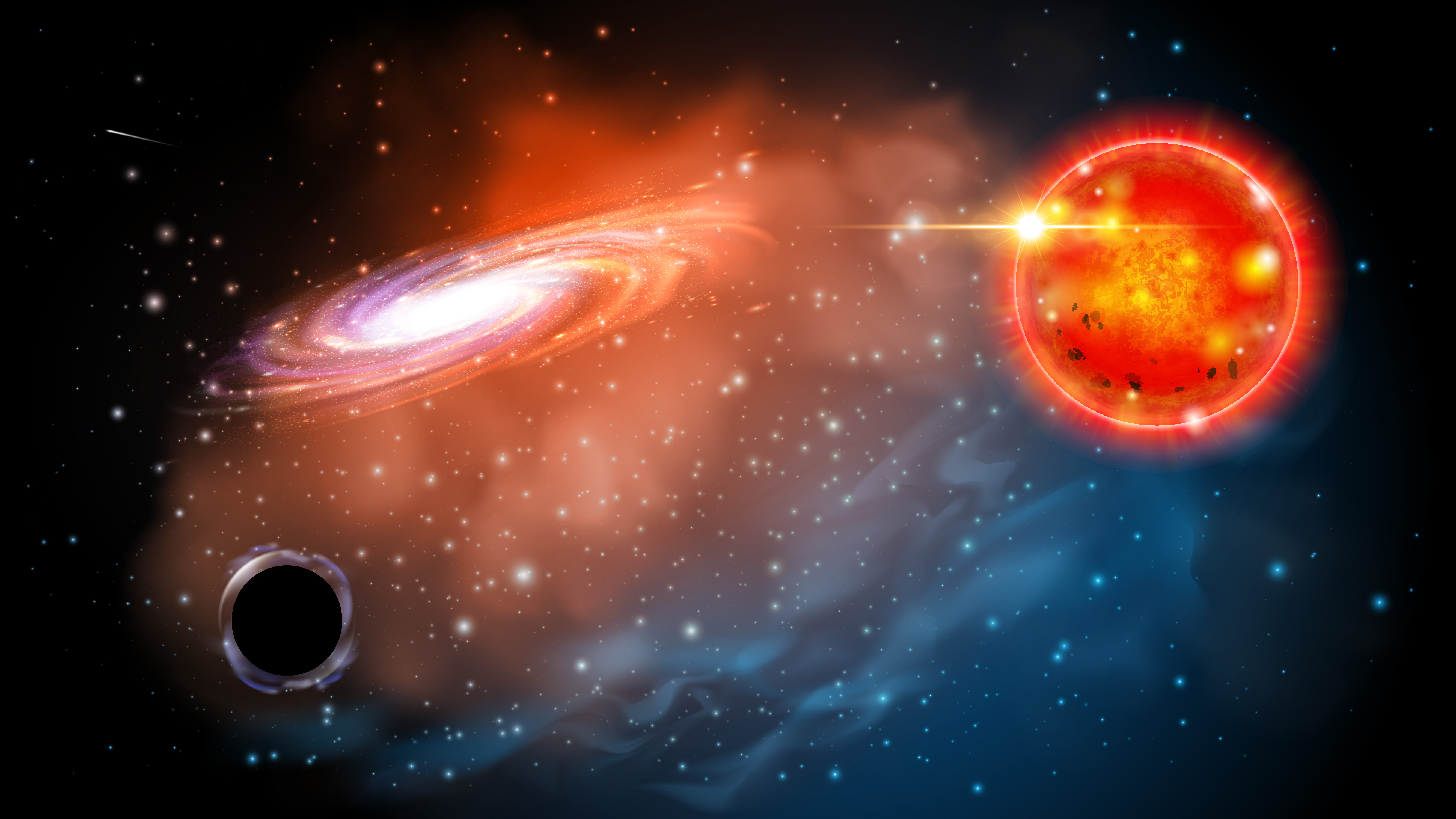

That's how the researchers discovered a massive dark object locked in a gravitational embrace with a rapidly rotating giant star about 10,000 light-years away at the far reaches of our galaxy, near the constellation Auriga. The researchers estimated the mass of this object to be around 3.3 times that of our sun, too massive to be a neutron star and not massive enough compared to any known black hole.

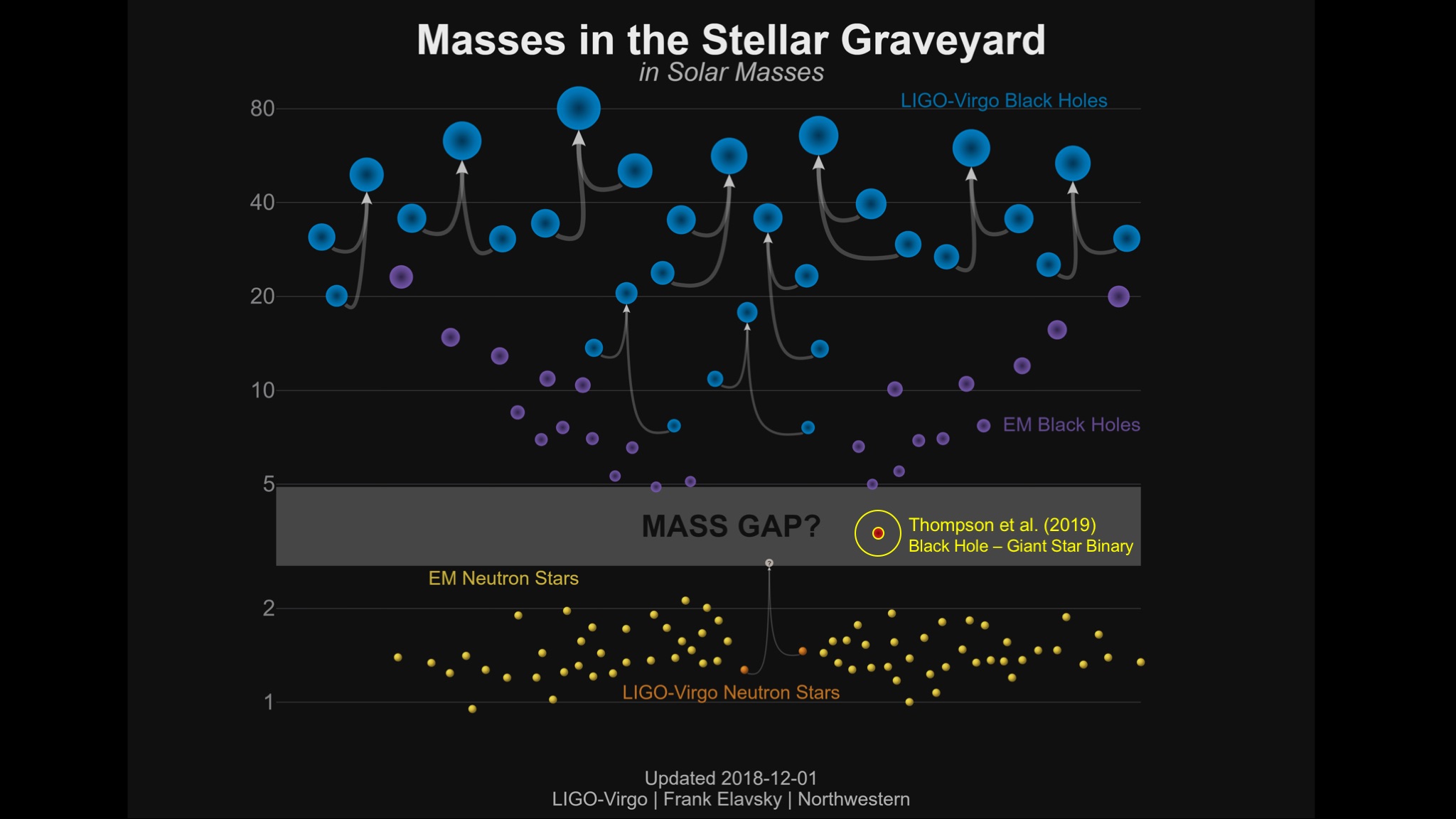

The most massive neutron star that scientists know of is 2.1 times the mass of our sun, whereas the least massive black hole known is about five to six times the mass of our sun, Thompson said. However, the newfound object's lower mass boundary — the lowest mass this object could be — is 2.6 times the mass of our sun, which is what astronomers think is the upper limit for how massive neutron stars can theoretically get. Any more massive than that, and the neutron star would collapse into a black hole.

So this dark, mysterious object "could be the most massive neutron star ever seen," right at the boundary after which it can't exist, Thompson said. "I would actually be even more excited if that were true." But more than likely, it's the hypothesized but never-before-discovered relatively low-mass black hole, he added.

Dejan Stojkovic, a cosmologist and professor of physics at the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences who was not involved with the research, agreed. "This is most likely a black hole," because it's too massive to be a neutron star, unless it's some sort of unusual star, Stojkovic told Live Science. "The finding[s] sound very reasonable," but not unexpected, as astronomers know that lower mass black holes exist.

Thompson said he looks forward to future discoveries, such as information about the incline of the star's orbit around the dark object that the European Space Agency's Gaia spacecraft might gather in an upcoming mission. This could help researchers measure the mass of the dark object more precisely.

The findings were published yesterday (Oct. 31) in the journal Science.

- 8 Ways You Can See Einstein's Theory of Relativity in Real Life

- 11 Fascinating Facts About Our Milky Way Galaxy

- From Big Bang to Present: Snapshots of Our Universe Through Time

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus