Details of stunning Maya acropolises and sophisticated civilization revealed by laser scans

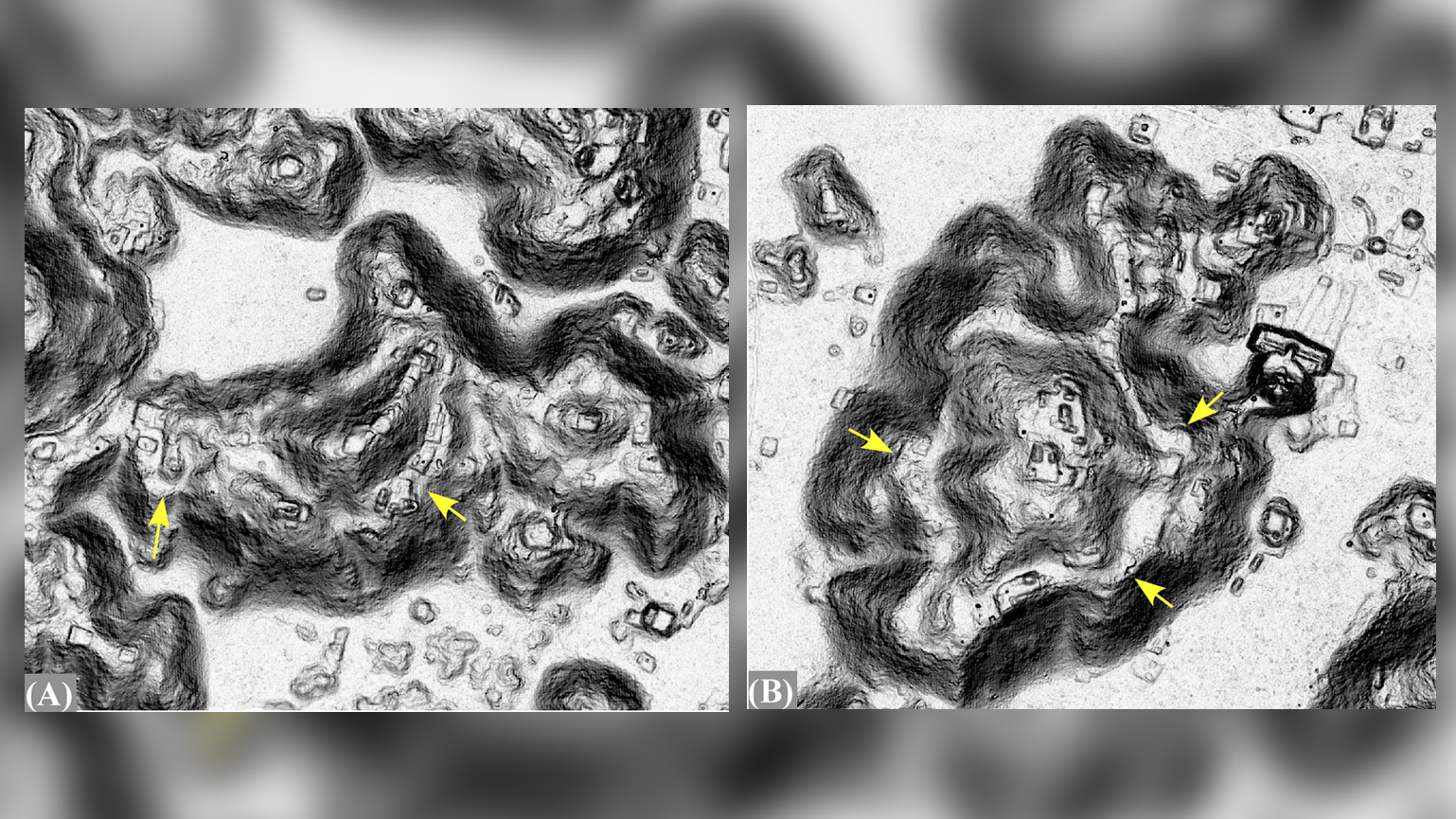

This is the first evidence of terracing in the Puuc region.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

By shooting billions of lasers at the ground, scientists have uncovered evidence of a sophisticated civilization left by the ancient Maya who lived in the northern Yucatán Peninsula in what is now Mexico, a new study finds.

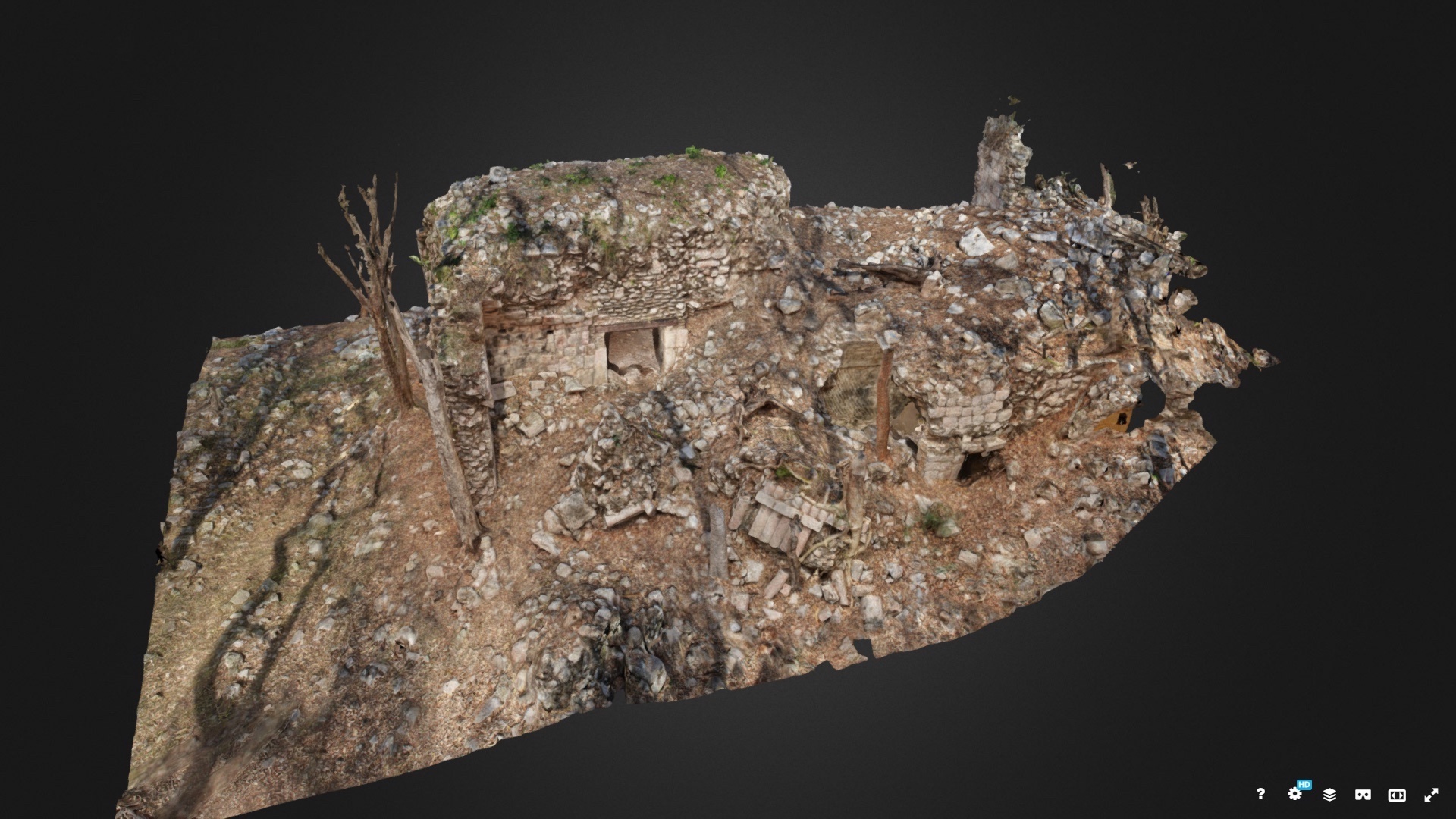

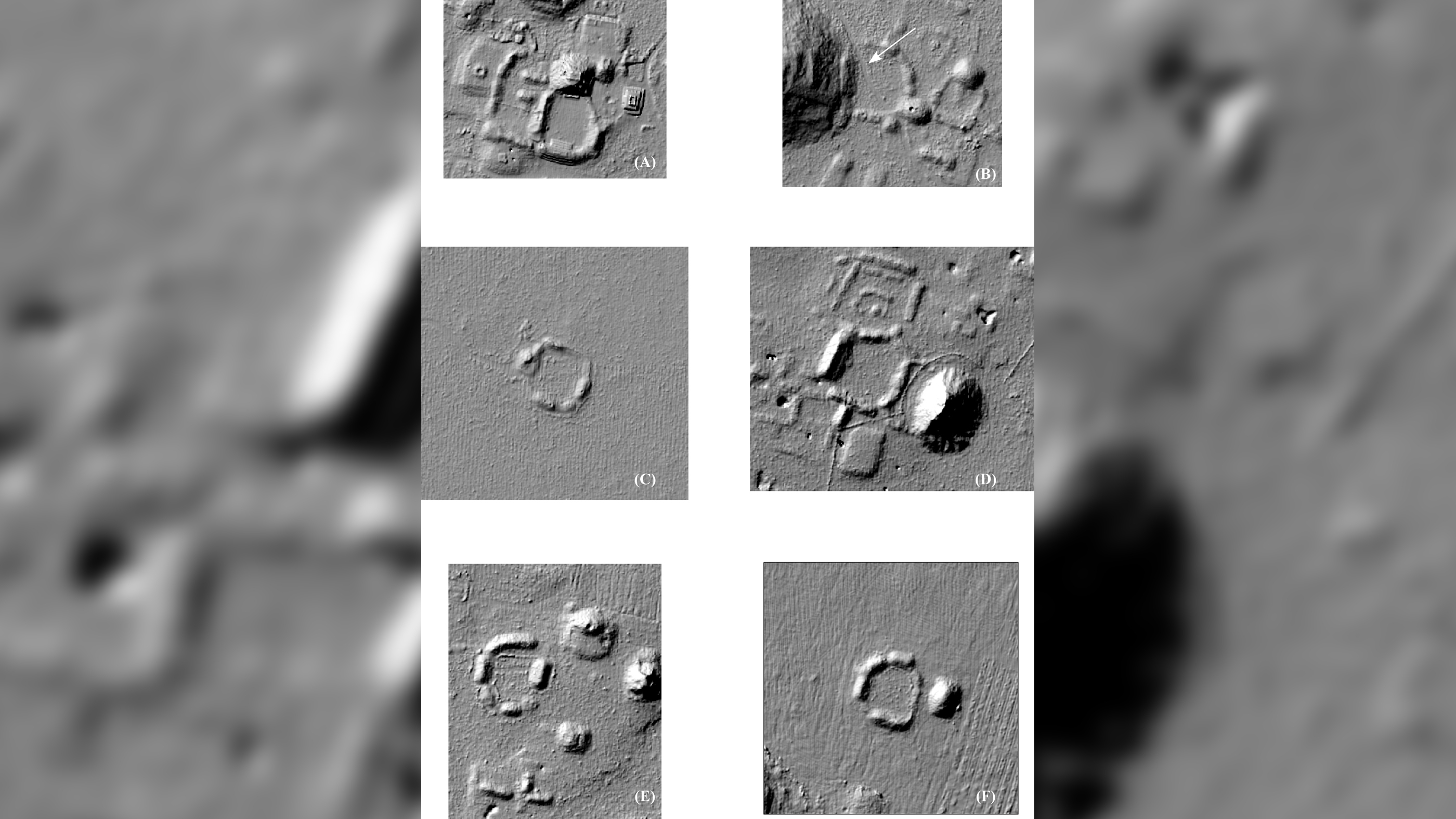

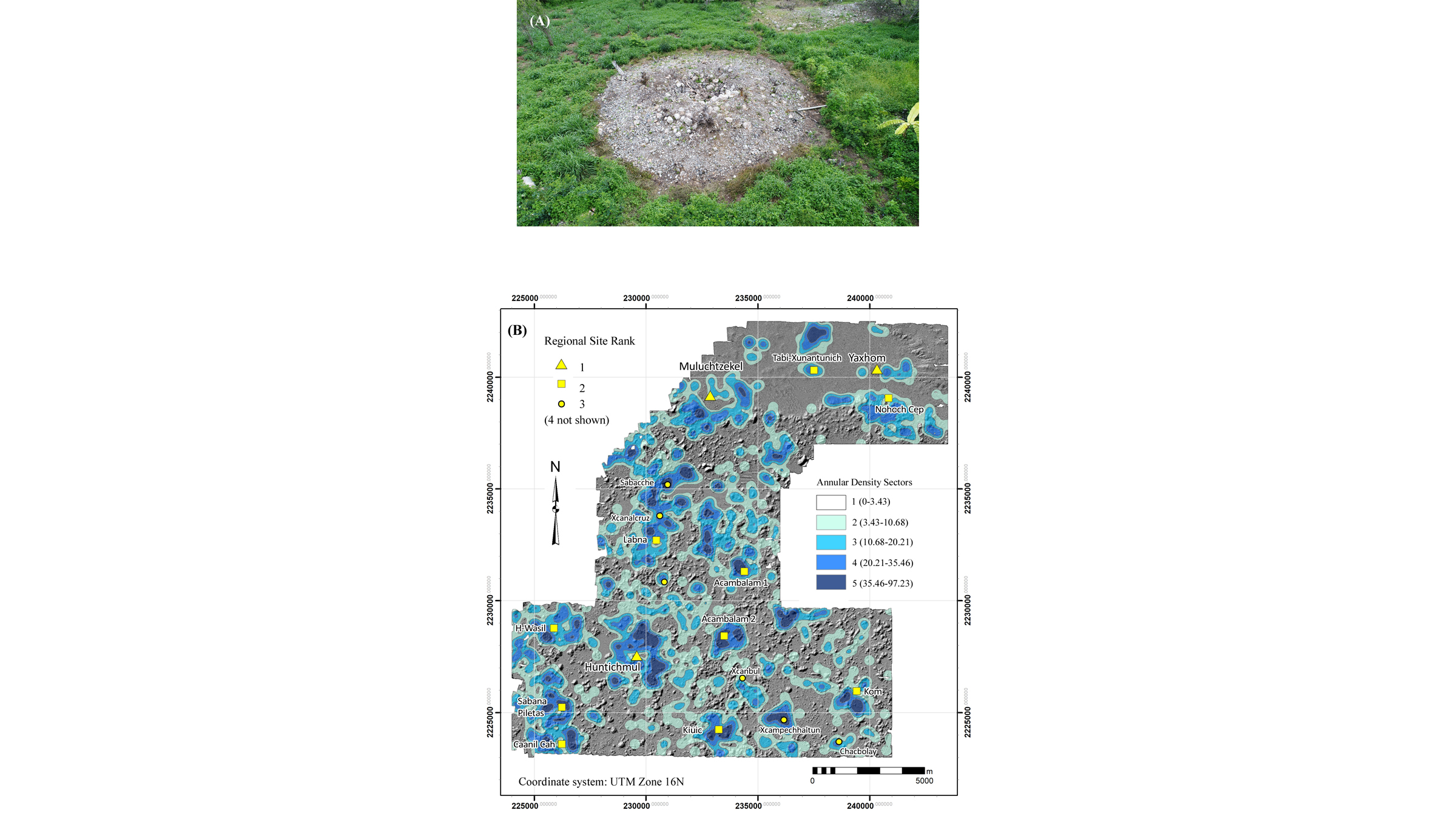

The laser survey revealed that in a region of the hilly northern Yucatán, known as the Puuc (pronounced "Pook"), the Maya built remarkable structures, including artificial reservoirs, more than 1,200 ovens, a handful of terraces for farming and nearly 8,000 platforms where houses were built. The ancient Maya also quarried the rock there, the laser scan revealed.

"It seems to have been a very prosperous area because we have all these masonry [stone] houses," study lead researcher William Ringle, a professor emeritus of anthropology at Davidson College in North Carolina, told Live Science. "It seems like people had access to what they needed."

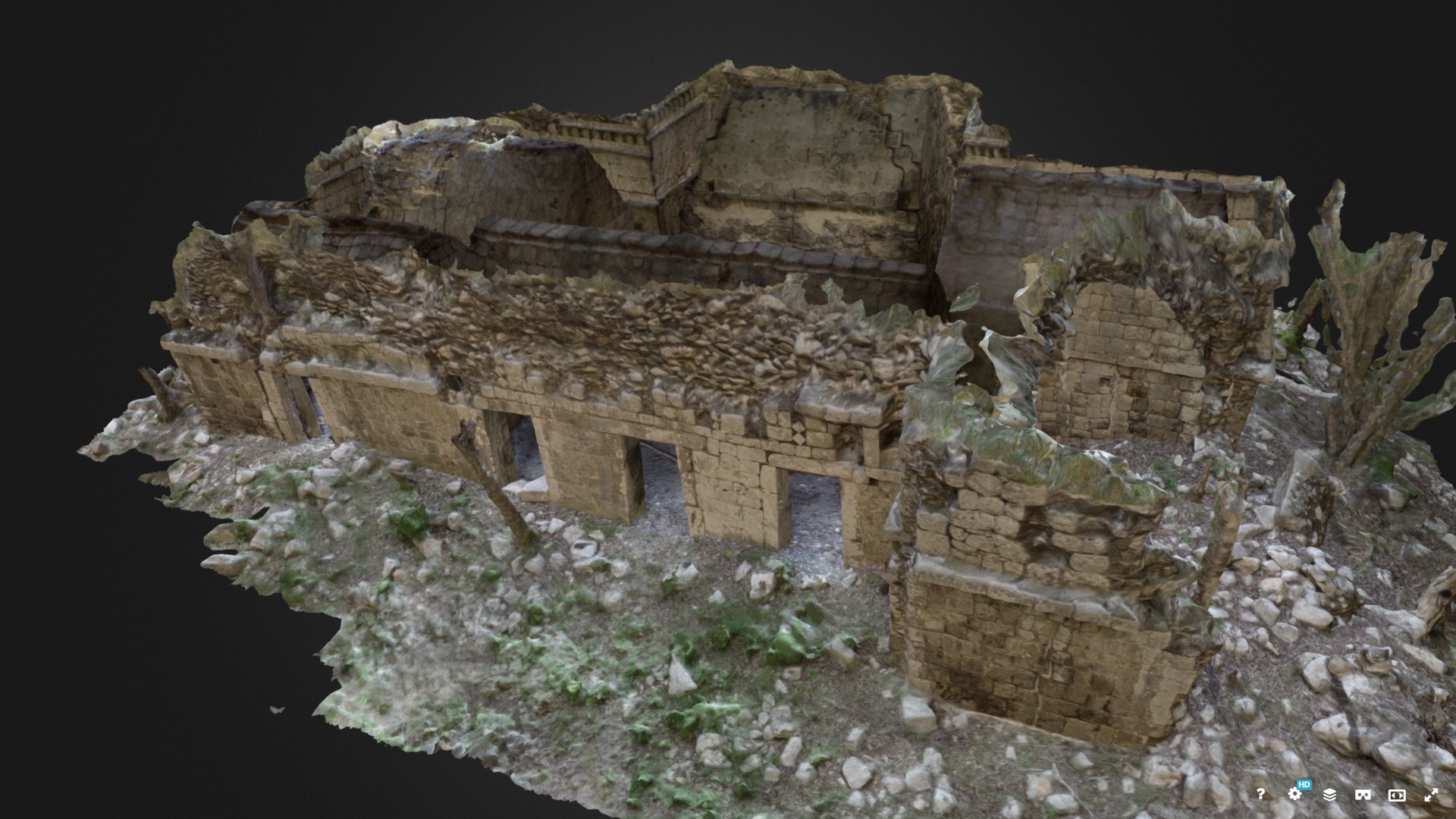

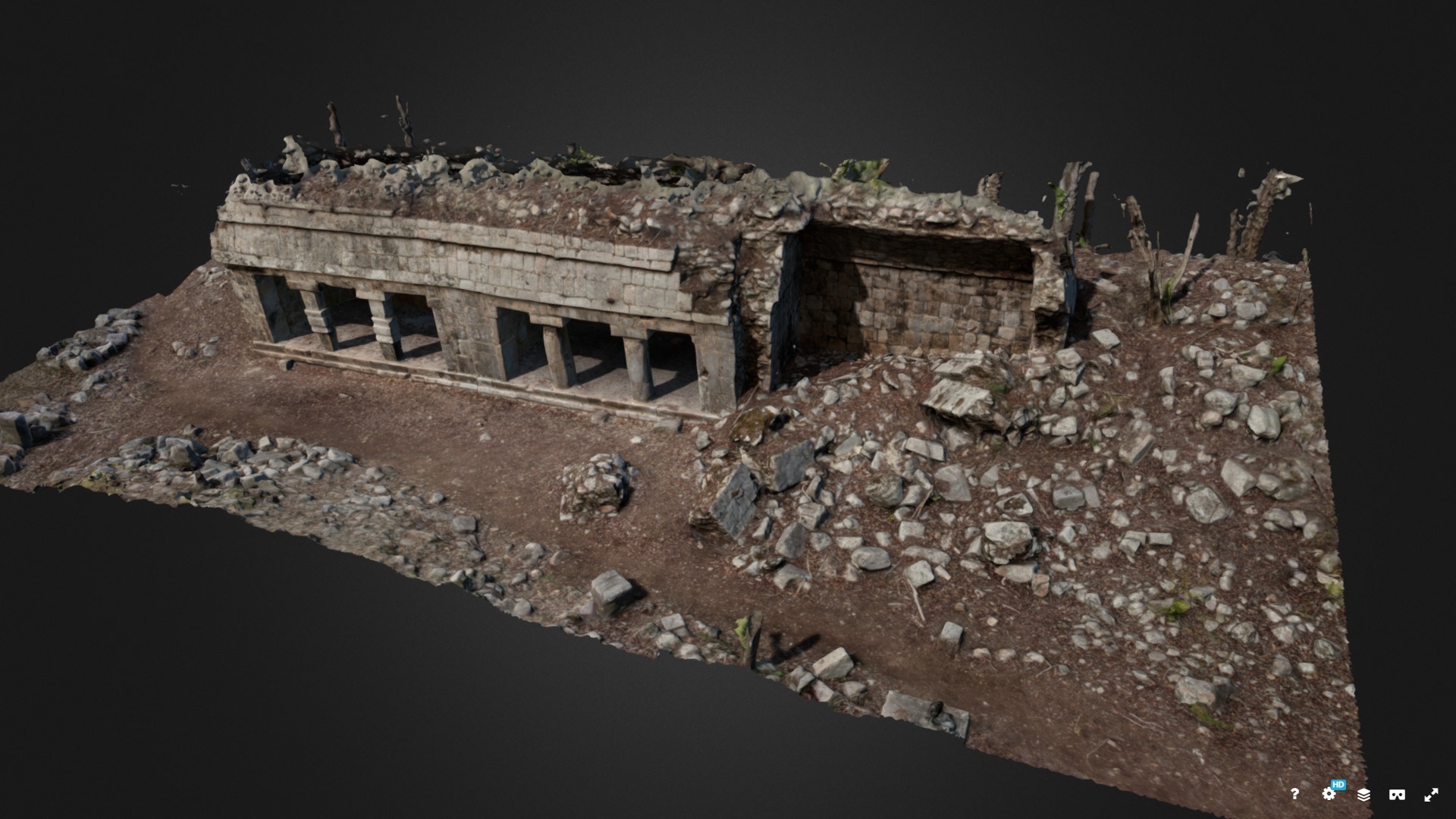

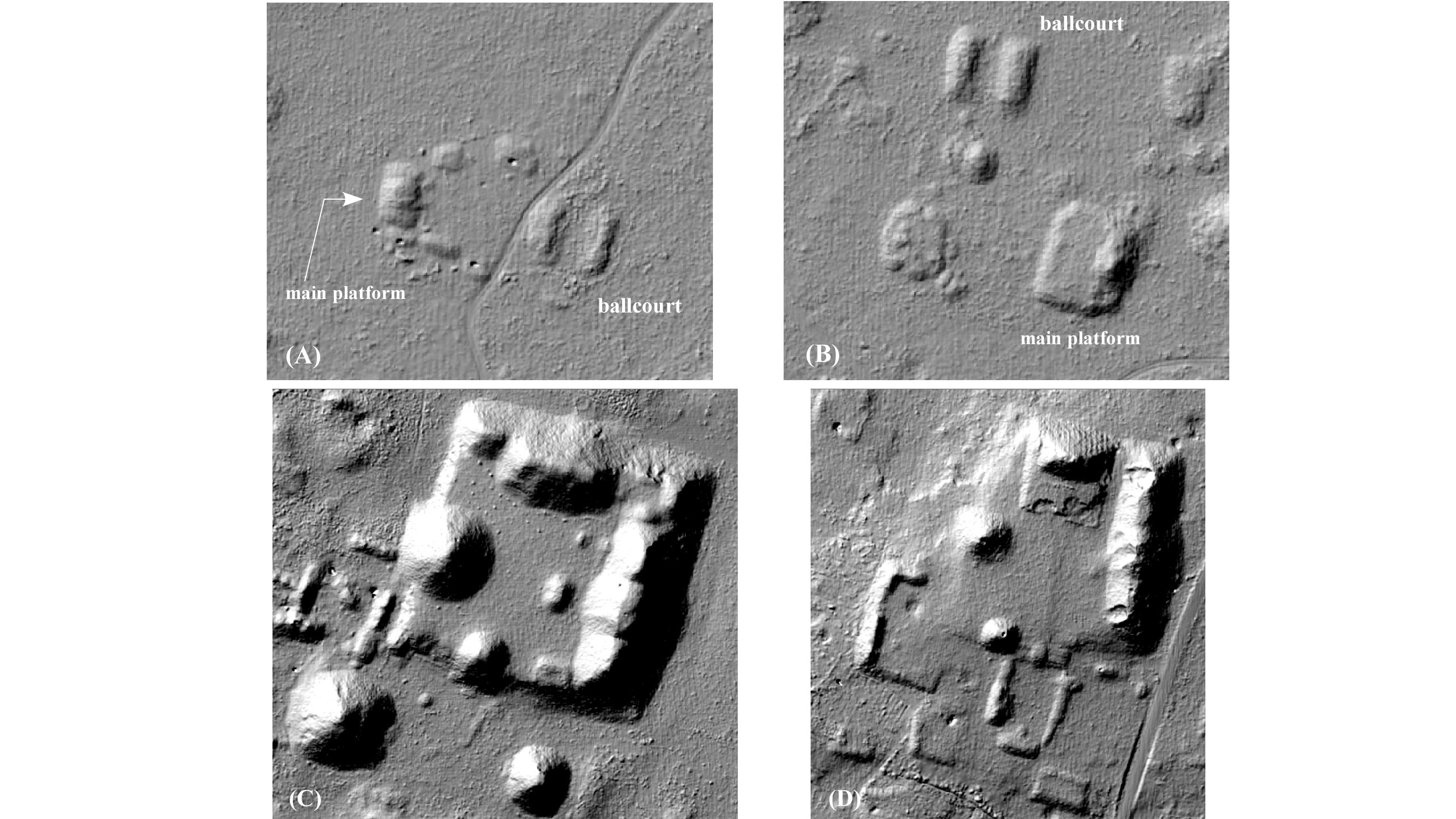

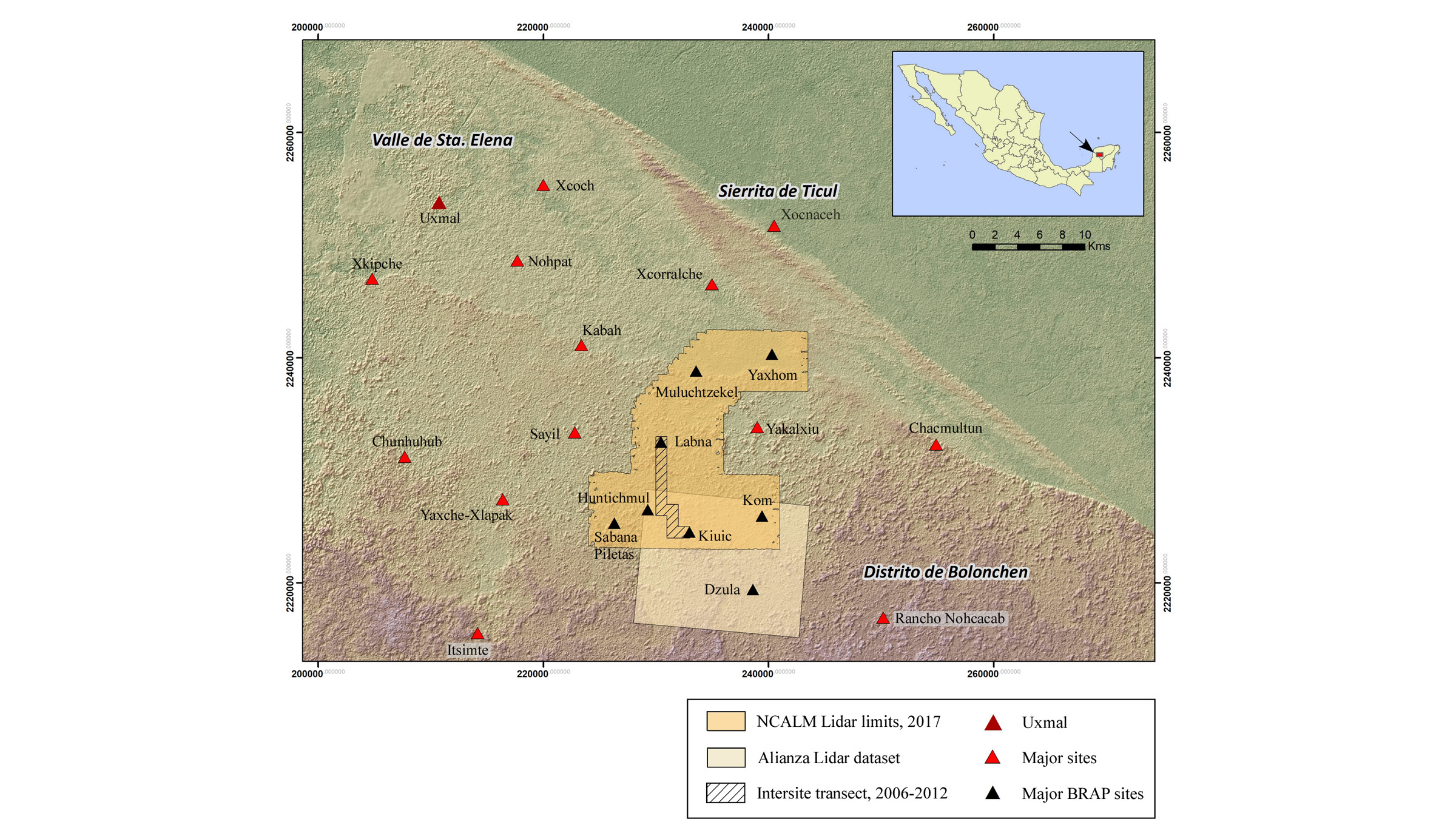

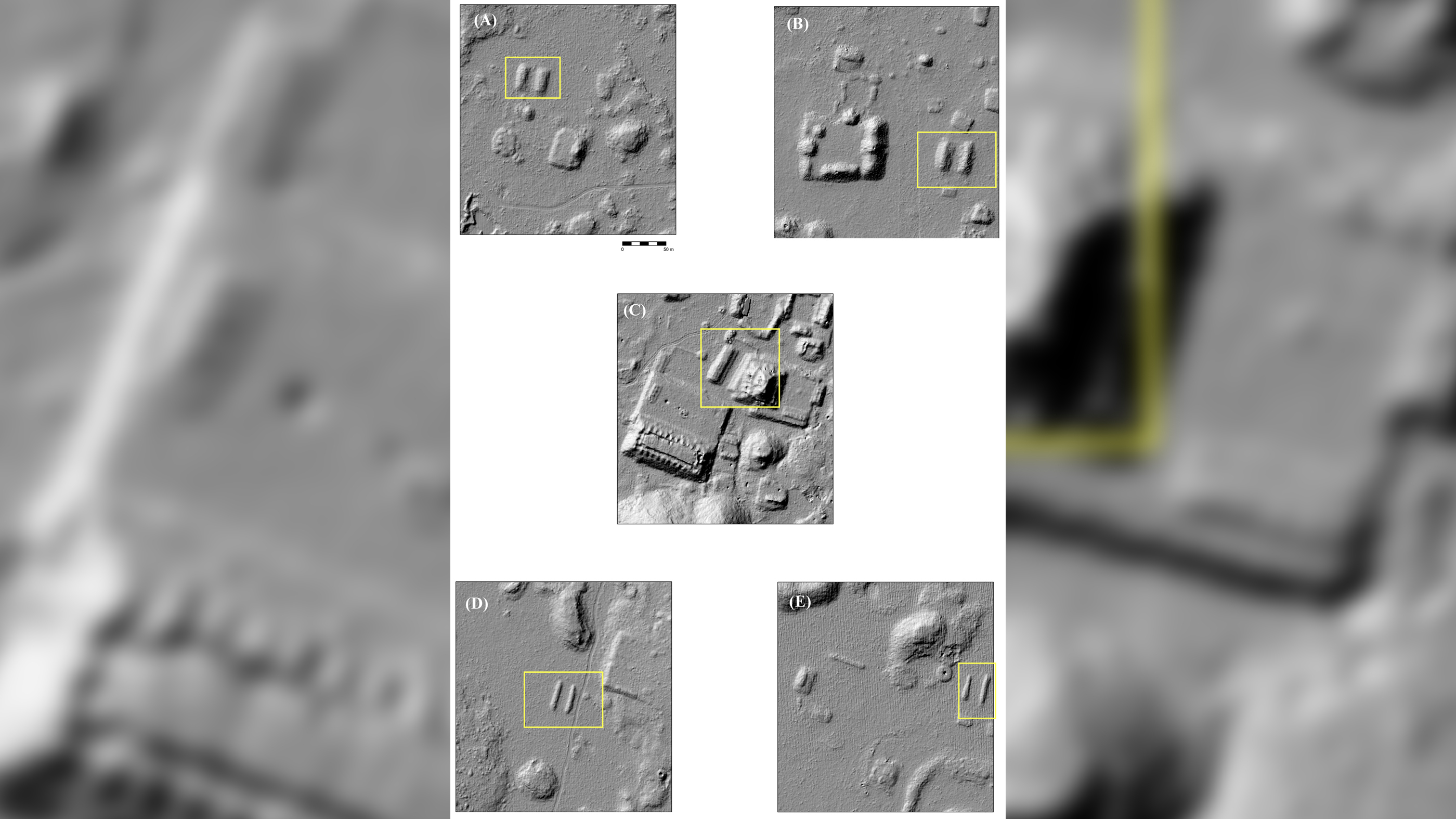

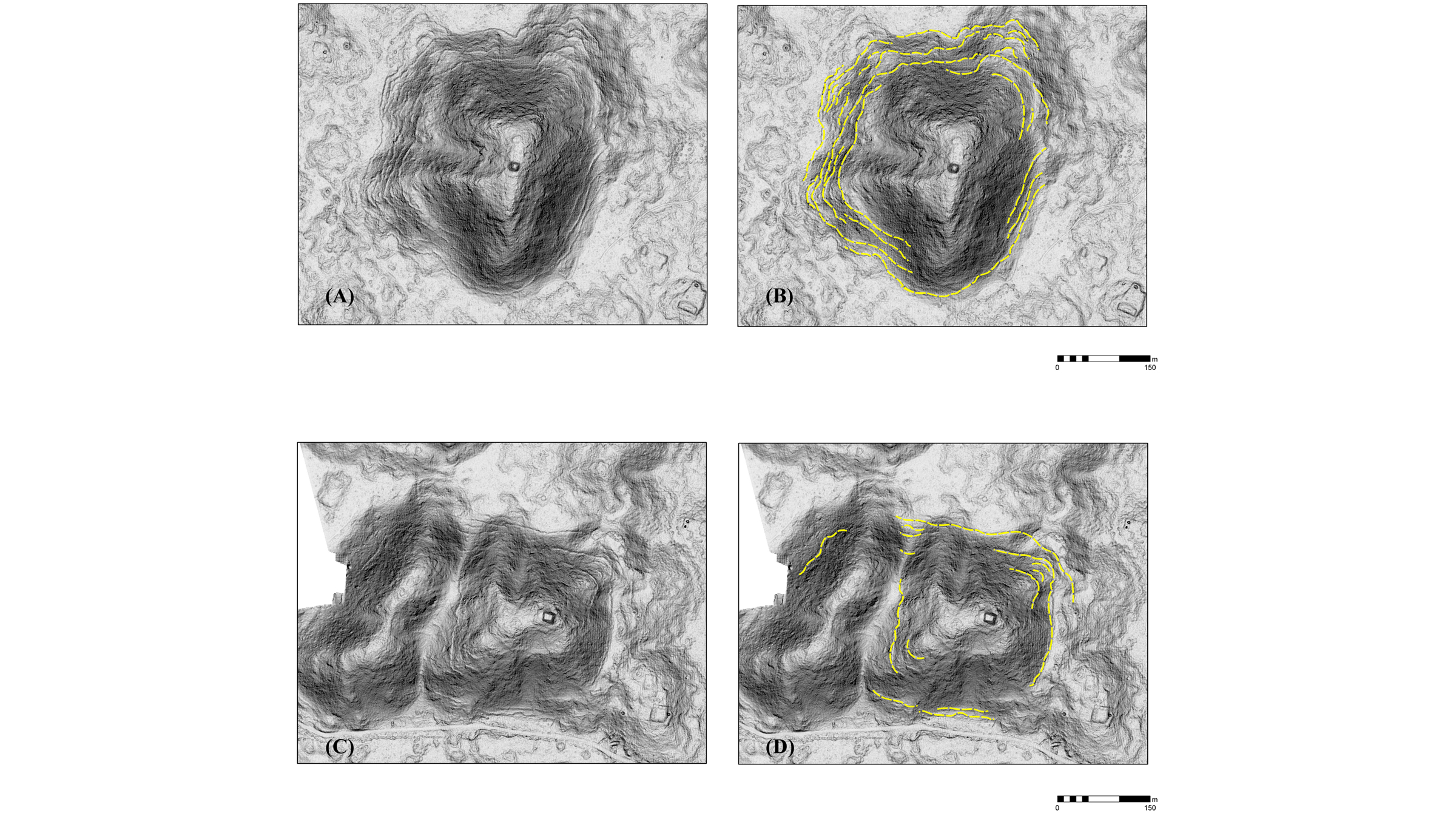

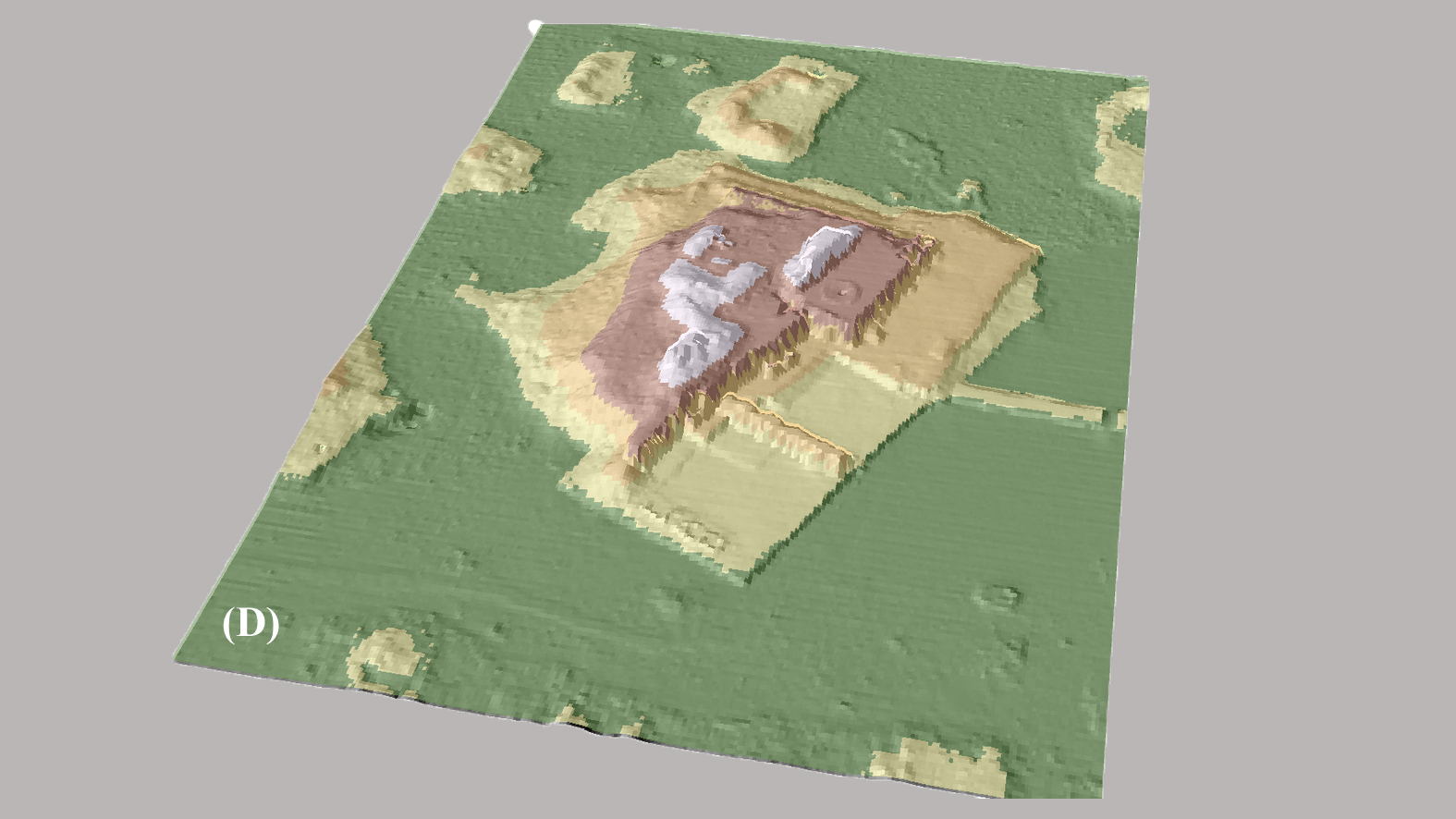

Moreover, the Maya in the Puuc built four large acropolises dating to the Middle Formative period (700 B.C. to 450 B.C.) and civic centers dating to A.D. 600 to 750, during the Late Classic. While these structures were already documented, an analysis of the laser data revealed that these Puuc communities had a distinct city layout that isn't seen in other Maya regions.

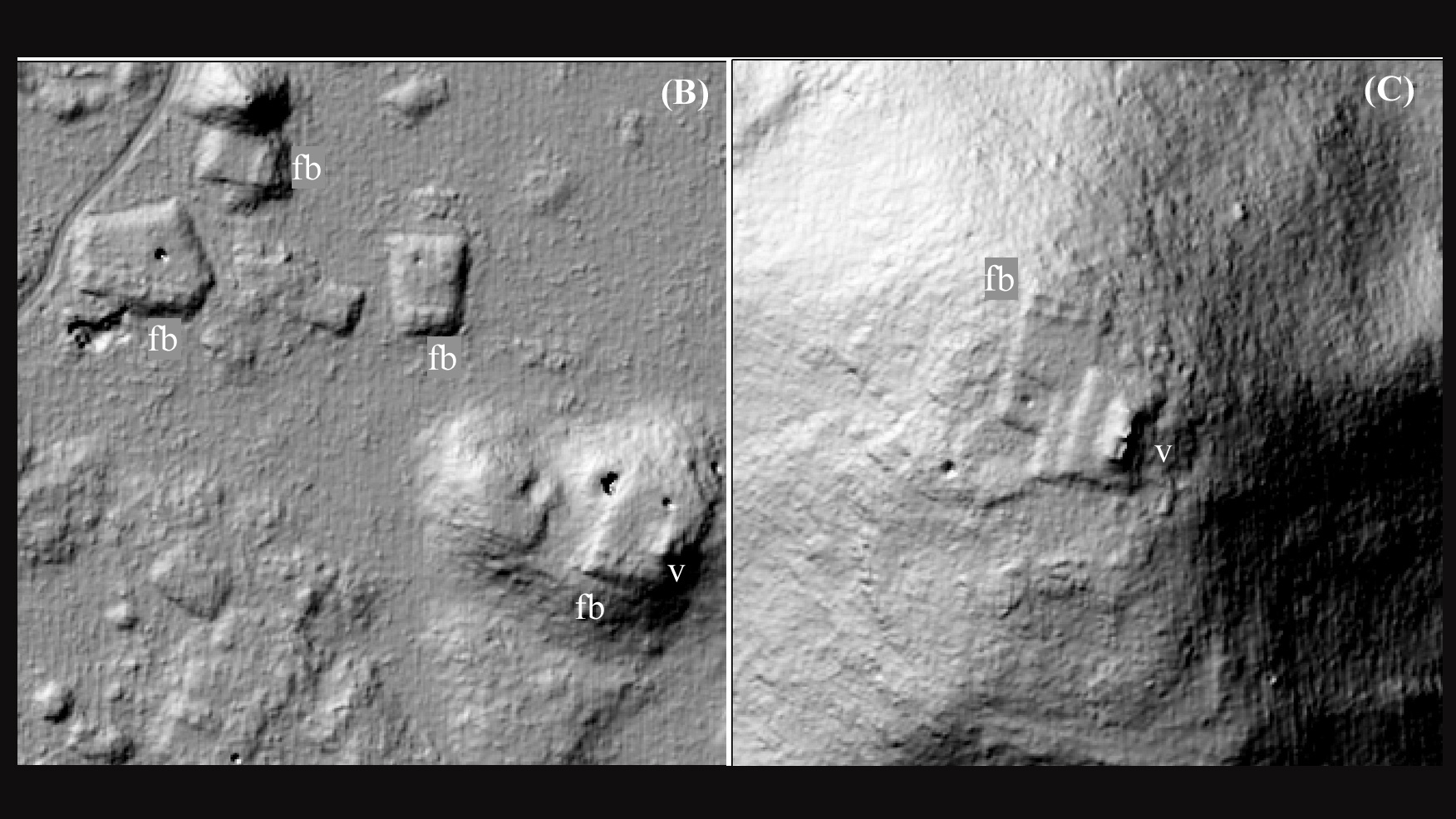

Related: Photos: Carvings depict Maya ballplayers in action

Researchers have known about the ancient Maya settlements in the Puuc since the 1840s, but there's never been a comprehensive lidar (light detection and ranging) survey of the region until now. With lidar, a machine aboard an aircraft shoots laser beams at the ground; these lasers can go through any intervening vegetation and then bounce back to the machine once they hit a solid object, such as rock or an ancient human-made structure. By calculating the time it takes for the laser light to return to the machine, software can create a detailed 3D map of the terrain.

Before arranging the May 2017 lidar survey, Ringle and his colleagues — study co-researcher Tomás Gallareta Negrón, an archaeologist at the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mérida, Mexico, and George Bey, an anthropologist at Millsaps College in Mississippi who wasn't involved in the new study — had spent about 20 years doing groundwork in the Puuc region.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Here, we had a guy fly over in two days [for the lidar survey], and we had more data than we could have ever obtained within ... our lifetimes," Ringle said.

Analyses of the lidar maps, which covered about 92.5 square miles (237 square kilometers), revealed about 7,900 housing platforms, including on the region's hills, indicating that the Puuc region had a large population that was largely concentrated across different communities, with a few houses in the Puuc's hinterlands. Many of these housing structures still had stone lines marking different rooms — there were about two to three rooms per house, Ringle said. These details suggest that the Puuc was likely "among the most densely settled within the Maya lowlands," an area that includes parts of modern-day Mexico, Guatemala and Belize, the researchers wrote in the study.

What's more, the team didn't find any evidence that the elite lived in affluent neighborhoods. "It wasn't a case of all the high-status people living in the center and as you moved away from the center, people got poorer and poorer," Ringle said. Rather, "we have these elite compounds dispersed throughout communities."

Despite being highly populated, it appears the people in the Puuc region were largely peaceful; the communities were fairly close to one another — usually about 3 to 6 miles (5 to 10 km) apart — but there wasn't evidence of defensive structures in any of them, the researchers found. "There are images of warriors on some of the sculptures," Ringle noted, "but it didn't get to the point where people were barricading themselves from their neighbors."

Related: Maya murals: Stunning images of king and calendar

Water challenges

A highly populated area needs a lot of water, but the Puuc, like the rest of the Yucatan, largely sits on limestone, a porous rock. Because of this, "there are no standing bodies of water or rivers or lakes," Ringle said. "So, across the entire northern peninsula, people had to find other ways to get drinking water."

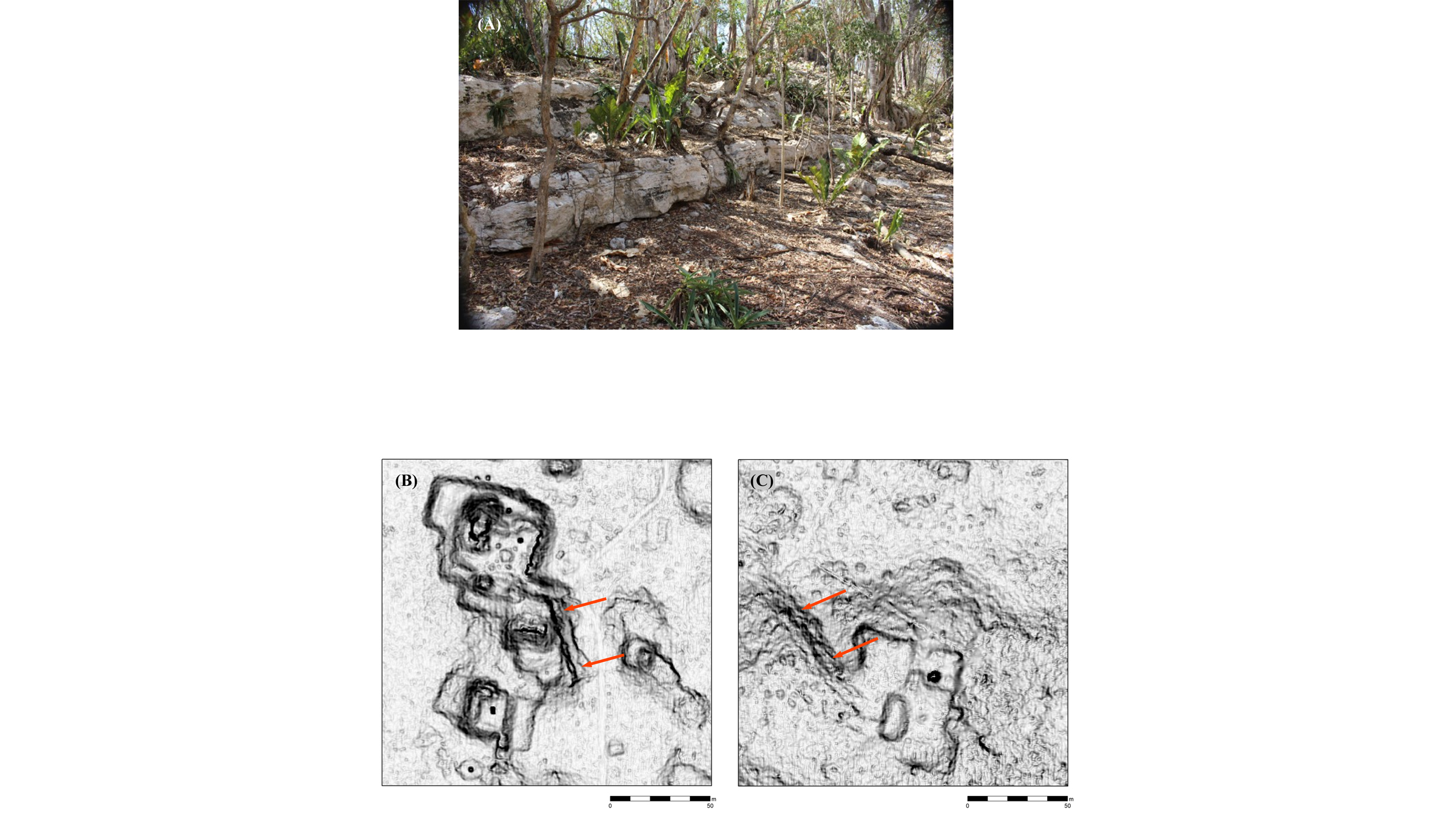

But the Puuc is situated on a hilly and raised area, making it high above the water table. To get around this, the Maya built "chultunes," or cisterns, lined with stucco plaster that collected rainwater. The Maya also built "aguadas," or reservoirs, with long channels that drained into them. The lidar survey revealed that some of these channels were several hundred meters long, "greatly enlarging the drainage area of [a] given aguada," the researchers wrote in the study. The lidar imagery revealed that few settlements were built near aguada beds — only 19 platforms that held houses were within 328 feet (100 meters) of an aguada, so perhaps close settlement to aguadas was discouraged, the researchers said.

However, 2,434, or 30%, of the housing platforms were within 0.6 miles (1 km) of an aguada, and 5,432, or 64%, were within 1.2 miles (2 km), the lidar survey showed. Though impressive, that finding means that more than one-third of platforms were far from an aguada, although it's possible that the people who lived in these houses had access to an aguada that was beyond the lidar survey area, the researchers said.

Between a stone and a farm place

The lidar survey also showed evidence for "an intensive and widespread" stone working industry, which included quarries and 1,232 circular ovens, which were likely used to heat sandstone so that lime, or calcium oxide, could be produced. This lime was probably used for mortar in construction and to help soften maize, which can make its nutrients easier to absorb.

"When people down there cook corn, they usually soak it in lime the night before to soften it up a little bit, and then they grind it," Ringle said. "So, lime was a necessary commodity, even at the household level."

The number of ovens the lidar revealed was surprising, Ringle added. Before, ground surveys had uncovered just about 40. "Now, with lidar, we have a sample of over 1,230," he said. "They're all over the place. And that indicates that it was a pretty big industry in the Puuc."

Related: Gallery: Excavating the oldest Maya observatory

Other research shows that these ovens could operate using very little firewood. "It tells us that people probably had the raw [fuel] materials fairly close at hand," Ringle said. "They hadn't burned down the entire forest — they could still walk and get fuel and walk back to their communities and do this kind of thing."

The lidar imagery also showed the "first unequivocal evidence for terracing in the Puuc, indeed in all northern Yucatan," the researchers wrote in the study. However, despite the region's hundreds of hills, just eight were terraced for farming, suggesting that the practice was not widespread in the Puuc, the team said.

Walk this way

While communities had internal roads marked with stones, often no longer than 0.6 miles (1 km) long, Puuc pathways between communities aren't always obvious to modern archaeologists, Ringle said. So, the team used the lidar map to create least-cost paths on the hilly terrain to guess where people probably walked. For instance, an algorithm helped the researchers determine whether it took more energy to go over or around a hill when walking from one Maya community to another, and would choose the path that took the least amount of energy, Ringle said.

"We looked at those hypothetical paths, and we found that, in many cases, there were other sites along them, so that was an interesting support that these might have been actual pathways that people took," Ringle said. "And in a couple of cases, some of these intervening sites are places where the hypothetical roads diverged."

Furthermore, many Puuc communities have civic buildings known as early Puuc civic complexes, which consisted of several buildings surrounding a plaza that were connected with ramps. These Puuc civic complexes tended to fall along these least-cost paths, Ringle said.

The new study is "very comprehensive," revealing new information about the Maya in general, as well as regional-specific practices in the Puuc, said Thomas Garrison, an assistant professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas at Austin who specializes in remote sensing technologies, such as lidar, but was not involved in the study.

The ancient Maya civilization existed for more than 2,500 years, before the people mysteriously abandoned their cities. Theories abound for why this happened. "[But] narratives that get put out there that the Maya mismanaged their landscape and this led to their own demise don't really work here," because, as the study and other research show, the Maya in the Puuc region are "very meticulous management of forest resources and careful control of water management," Garrison told Live Science.

The study was published online Wednesday (April 28) in the journal PLOS One.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus