Archaeologists have found the lair of an exiled Anglo-Saxon hermit king

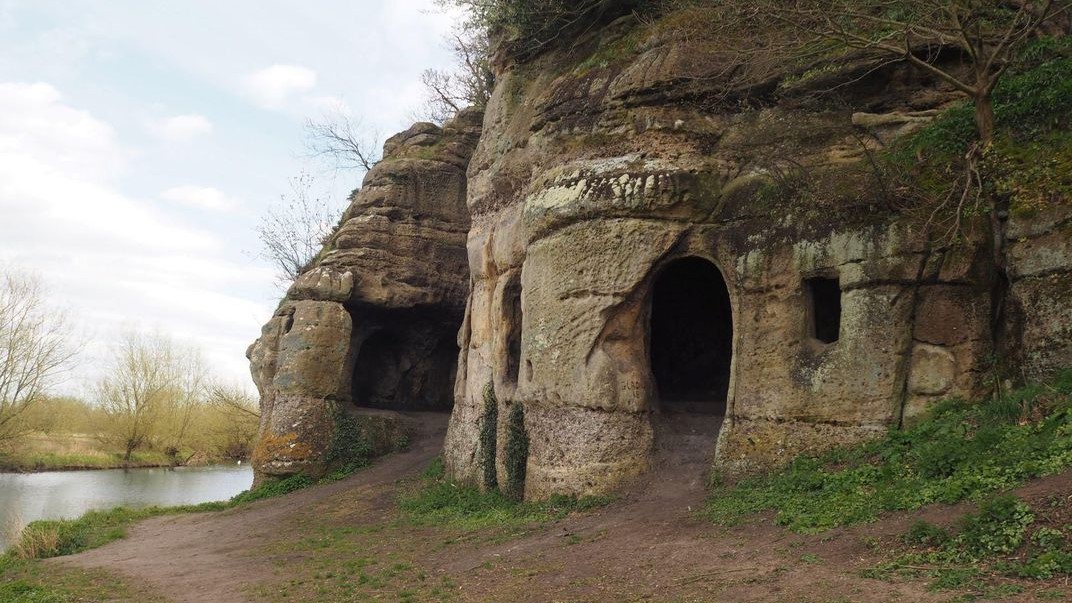

Anchor Church cave could be one of the oldest intact domestic interiors in the UK.

A British cave dwelling has been identified as the refuge for an exiled Anglo-Saxon king, according to archaeologists.

Anchor Church Caves, located by the River Trent in a secluded part of the countryside in central England, was long considered to be an 18th-century "folly" — an extravagant building made solely for ornamentation or as a joke.

But a new study has revealed that the cave house is the real deal. The 1,200-year-old structure was built during the tumultuous life of the Northumbrian king Eardwulf, who was hounded from his throne to live as a hermit, and later became a saint.

Related: Family ties: 8 truly dysfunctional royal families

Local legend said Eardwulf, or St. Hardulph as he was later known, lived inside the cave dwelling after he was deposed and exiled for mysterious reasons in A.D. 806. A fragment from a 16th-century book states that Eardwulf ''has a cell in a cliff a little from the Trent,'' and the banished king was buried in A.D. 830 at a location just 5 miles (8 kilometers) from the cave.

Edmund Simons, an archaeologist at the Royal Agricultural University in England and the principal investigator of the project, is convinced that Eardwulf lived in the caves under the watchful eyes of his enemies.

"The architectural similarities with Saxon buildings, and the documented association with Hardulph/Eardwulf, make a convincing case that these caves were constructed, or enlarged, to house the exiled king," Simons said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eardwulf lived and ruled during a time of persistent political instability in medieval England. During the seventh, eighth and ninth centuries, seven key kingdoms and over 200 kings intrigued, murdered and warred against each other in a fervent, constant scramble for supremacy.

Eardwulf took the throne in A.D. 796 after the killing of his two immediate predecessors, and ruled Northumbria for only 10 years before he was chased from power (possibly, according to some scholars, by his own son) to spend his remaining years in exile in the rival kingdom of Mercia.

With all of this civil strife, hiding in a cave with the remainder of one’s disciples was far from the most abnormal idea Eardwulf could have come up with, Simons said.

"It was not unusual for deposed or retired royalty to take up a religious life during this period, gaining sanctity and in some cases canonization," he said. "Living in a cave as a hermit would have been one way this could have been achieved."

The researchers reconstructed the original plan of the caves, which includes three rooms and an easterly facing chapel, using detailed measurements, a drone survey, and a careful study of the architectural features — which closely resemble other Saxon architecture. Despite having been overlooked by historians until recently, cave dwellings may be "the only intact domestic buildings to have survived from the Saxon period," Simons said. The team has identified over 20 other cave houses in west-central England that could date back as far as the fifth century.

The Anchor Church Caves were later modified in the 18th century, according to the team, when it was written that the English aristocrat Sir Robert Burdett "had it fitted up so that he and his friends could dine within its cool and romantic cells," according to the researchers. Burdett added brickwork and window frames to the caves, as well as widening the openings so that well-dressed women could enter, the statement said.

"It is extraordinary that domestic buildings over 1,200 years old survive in plain sight, unrecognized by historians, antiquarians and archaeologists" Mark Horton, a professor of archaeology at the Royal Agricultural University, who is leading excavations of Viking and Anglo-Saxon remains at Repton, close to the caves, said in the statement. "We are confident that other examples are still to be discovered to give a unique perspective on Anglo-Saxon England."

The researchers published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus